Aluminum Sheet Fabrication Decoded: From Raw Metal To Finished Part

Understanding Aluminum Sheet Fabrication Fundamentals

Ever wondered how that sleek aluminum enclosure on your electronics or the lightweight panel on a modern vehicle comes to life? It all starts with a flat metal sheet and a series of precise manufacturing operations. Aluminum sheet fabrication is the process of transforming flat aluminum sheets into functional components through cutting, bending, forming, and joining operations. Unlike aluminum extrusion, which pushes metal through a die to create specific profiles, or casting, which pours molten metal into molds, this method works exclusively with flat stock material available in various gauges and thicknesses.

So, is aluminum a metal? Absolutely. Aluminum is a versatile metallic element that ranks as the third most abundant element in Earth's crust. What makes it exceptional for metal fabrication isn't just its metallic properties but its unique combination of characteristics that few other materials can match. It's lightweight, naturally corrosion-resistant, and highly formable, making aluminum sheet metal a go-to choice for manufacturers across countless industries.

Aluminum weighs roughly one-third as much as steel while maintaining an excellent strength-to-weight ratio, making it possible to achieve required durability while significantly reducing overall material weight.

This weight advantage, as noted by industry experts, proves particularly beneficial for fuel efficiency in transportation and load reduction in structural designs. You'll find aluminum fabrication applications everywhere, from automotive body panels and aerospace components to architectural facades and HVAC ductwork.

What Sets Aluminum Sheet Fabrication Apart from Other Metalworking Processes

Sheet metal fabrication stands distinct from other metalworking methods in several important ways. When you're working with an aluminum sheet, you're starting with a flat, uniform material that maintains consistent thickness throughout. This differs fundamentally from processes like:

- Extrusion – Forces aluminum through shaped dies to create continuous profiles with fixed cross-sections

- Casting – Pours molten aluminum into molds for complex three-dimensional shapes

- Forging – Uses compressive forces to shape solid aluminum billets

The beauty of working with flat stock lies in its versatility. A single metal sheet can be laser cut into intricate patterns, bent into precise angles, formed into curved surfaces, and joined with other components to create everything from simple brackets to complex assemblies. This flexibility makes sheet metal fabrication ideal for both prototyping and high-volume production runs.

The Core Characteristics That Make Aluminum Ideal for Sheet Forming

Why does aluminum dominate so many fabrication applications? The answer lies in its remarkable combination of physical and mechanical properties:

- Lightweight construction – At approximately 2.7 g/cm³, aluminum enables significant weight savings without sacrificing structural integrity

- Natural corrosion resistance – Aluminum naturally forms a protective oxide layer that shields it from moisture, chemicals, and harsh environmental conditions

- Excellent formability – The material bends and shapes readily without cracking, allowing for complex geometries

- High thermal conductivity – Makes it perfect for heat sinks and thermal management applications

- Recyclability – Aluminum can be recycled indefinitely without losing its properties, supporting sustainable manufacturing

These characteristics explain why industries from automotive to aerospace rely heavily on aluminum fabrication. The automotive sector uses it for body panels and structural components to improve fuel efficiency. Aerospace manufacturers depend on high-strength aluminum alloys for aircraft skins and structural elements. Architects specify it for building facades that resist weathering for decades. Each application leverages aluminum's unique balance of strength, weight, and workability.

As manufacturing technology advances, the capabilities of this fabrication method continue to expand. Modern laser cutting and CNC machining enable precision previously impossible, while automated forming equipment ensures consistency across thousands of identical parts. Understanding these fundamentals sets the foundation for exploring specific alloys, processes, and applications in the sections ahead.

Selecting the Right Aluminum Alloy for Your Project

Now that you understand the fundamentals, here's where things get practical. Choosing the right aluminum alloy can make or break your fabrication project. Each alloy grade brings distinct characteristics that affect how it cuts, bends, welds, and performs in its final application. Get this decision wrong, and you might end up with cracked parts, failed welds, or components that can't withstand their intended environment.

Think of aluminum alloys like different recipes. Pure aluminum serves as the base ingredient, but adding elements like magnesium, silicon, zinc, or copper creates dramatically different performance profiles. The four most common grades you'll encounter in aluminum alloy sheets are 3003, 5052, 6061, and 7075. Each excels in specific situations, and understanding their differences helps you make smarter material choices.

Matching Aluminum Alloys to Your Fabrication Requirements

Let's break down what each grade brings to the table:

3003 Aluminum offers excellent formability at an economical price point. With manganese as its primary alloying element, it bends and shapes easily without cracking. You'll find this grade in general-purpose applications like HVAC ductwork, storage tanks, and decorative trim where extreme strength isn't critical but workability matters.

5052 Aluminium steps up the performance with magnesium and chromium additions that deliver superior corrosion resistance and weldability. This grade handles salt water, chemicals, and harsh environments remarkably well. Marine applications like boat hulls, fuel tanks, and fittings rely heavily on 5052 aluminum sheet metal for exactly these reasons.

6061 Aluminum introduces heat-treatability to the equation. The T6 temper delivers approximately 32% higher ultimate strength than 5052, making it ideal for structural components like bridges, aircraft frames, and machinery. It machines beautifully and welds well, though its reduced ductility means larger bend radii are required.

7075 Aluminum represents the high-strength end of the spectrum. Significant zinc, magnesium, and copper content produces durability approaching titanium alloys. Aerospace applications, high-performance vehicle frames, and sporting equipment demand this grade when maximum strength-to-weight ratios are non-negotiable. However, this strength comes at a cost—7075 is notoriously difficult to bend and weld.

Why 5052 Dominates Sheet Metal Applications

Is 5052 aluminum bendable? Absolutely—and that's precisely why fabricators reach for it so often. The H32 temper designation means this aluminium alloy sheet has been strain-hardened and stabilized, giving it enough ductility to handle cold working operations without cracking. You can form tight radii, create hems, and execute offset bends that would cause other alloys to fail.

According to industry fabrication experts, 5052 is more readily available in aluminum sheets than 6061 or 7075, making it easier to source with shorter lead times. This availability, combined with its forgiving nature during forming operations, makes alum 5052 H32 the default recommendation for prototype and low-volume production work.

Marine grade aluminum 5052 particularly shines in outdoor and saltwater environments. Unlike some alloys that require protective coatings to resist corrosion, 5052 performs admirably even without additional finishing. This reduces both cost and complexity for applications exposed to moisture or chemicals.

Here's the fundamental trade-off you need to understand: higher strength alloys typically sacrifice formability. The same molecular structure that gives 7075 its exceptional strength makes it brittle during bending operations. Meanwhile, 5052's more relaxed structure allows material flow during forming but limits absolute strength. Your application requirements should drive this decision.

| Alloy | Formability Rating | Weldability | Corrosion Resistance | Typical Applications | Best Fabrication Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3003 | Excellent | Excellent | Good | HVAC ductwork, storage tanks, decorative trim | Bending, forming, spinning, welding |

| 5052 | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Marine components, fuel tanks, automotive panels | Bending, forming, welding, deep drawing |

| 6061 | Fair | Excellent | Good | Structural components, aircraft frames, machinery | Machining, welding, limited bending with larger radii |

| 7075 | Poor | Fair | Good | Aerospace parts, high-performance frames, defense components | Machining, laser cutting; avoid bending and welding |

When evaluating these options, consider your complete fabrication sequence. A part requiring multiple bends and welded joints points toward 5052. A machined component needing heat treatment and moderate forming might suit 6061. A load-bearing aerospace bracket demanding maximum strength with no forming? That's 7075 territory. Understanding these distinctions before you specify materials prevents costly redesigns and manufacturing failures down the line.

Aluminum Sheet Thickness and Gauge Selection Guide

You've selected your alloy—now comes another critical decision that trips up even experienced engineers. What thickness do you actually need? If you've ever looked at a sheet metal gauge chart and felt confused by conflicting numbers, you're not alone. The gauge system dates back to the 1800s when manufacturers measured wire thickness by counting drawing operations rather than using standardized units. This legacy creates a counterintuitive reality: higher gauge numbers mean thinner material, and the same gauge number means different thicknesses for different metals.

Understanding sheet metal thickness aluminum specifications is essential because ordering the wrong gauge can derail your entire project. A 10-gauge aluminum sheet is noticeably thinner than 10-gauge steel, and mixing up these charts leads to parts that don't fit, can't handle their intended loads, or cost more than necessary.

The Aluminum vs Steel Gauge Difference You Must Understand

Here's the critical point many fabricators miss: aluminum and steel use completely different gauge standards. According to SendCutSend's gauge thickness guide, the difference between 10-gauge stainless steel and 10-gauge aluminum is 0.033 inches—well outside acceptable tolerances for most designs. Using the wrong gauge chart can result in parts that are either too flimsy or unnecessarily heavy and expensive.

Why does this discrepancy exist? The gauge system originated in wire manufacturing, where the number represented how many times wire was drawn through progressively smaller dies. Different metals behave differently during drawing operations due to their unique material properties. This means each material developed its own gauge conversion standards over time.

Consider this comparison:

- 10-gauge aluminum measures 0.1019 inches (2.588 mm)

- 10-gauge mild steel measures 0.1345 inches (3.416 mm)

- 10-gauge stainless steel measures 0.1406 inches (3.571 mm)

That's a significant difference. If you're transitioning a design from steel to aluminum for weight savings, you can't simply specify the same gauge number and expect equivalent performance. The 10ga aluminum thickness is roughly 24% thinner than its steel counterpart, which affects structural integrity, bend behavior, and fastener compatibility.

Similarly, 11 gauge steel thickness comes in at approximately 0.1196 inches, while aluminum at the same gauge measures just 0.0907 inches. Always verify you're referencing the correct material-specific gauge size chart before finalizing specifications.

Choosing Gauge Thickness Based on Load Requirements

Selecting the appropriate gauge depends on your application's functional demands. Here's a practical framework:

Thinner gauges (20-24) work well for decorative applications, light-duty covers, and components where weight minimization trumps structural requirements. At 20 gauge, aluminum measures just 0.0320 inches (0.813 mm)—thin enough for intricate forming but insufficient for load-bearing applications. Think decorative panels, electronic enclosures with minimal structural demands, and cosmetic trim pieces.

Medium gauges (14-18) handle most structural panels and enclosures. A 14 gauge steel thickness equivalent in aluminum measures 0.0641 inches (1.628 mm), providing enough rigidity for equipment housings, HVAC components, and automotive body panels. This range balances formability with structural performance, making it the workhorse thickness for general fabrication.

Heavier gauges (10-12) deliver the rigidity needed for load-bearing components, structural brackets, and applications subject to significant stress or impact. At 10 gauge, you're working with material over 2.5 mm thick—substantial enough to support considerable loads while still remaining formable with appropriate equipment.

So how many mm is a 6 gauge? While 6 gauge falls outside typical sheet metal territory and into plate thickness, the inverse relationship continues. Lower gauge numbers consistently indicate thicker material across all gauge sizes.

| Gauge Number | Thickness (inches) | Thickness (mm) | Typical Applications | Weight per Sq Ft (lbs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.1019 | 2.588 | Heavy structural brackets, load-bearing panels | 1.44 |

| 12 | 0.0808 | 2.052 | Structural components, heavy-duty enclosures | 1.14 |

| 14 | 0.0641 | 1.628 | Equipment housings, automotive panels | 0.91 |

| 16 | 0.0508 | 1.290 | HVAC ductwork, general enclosures | 0.72 |

| 18 | 0.0403 | 1.024 | Light enclosures, electronic housings | 0.57 |

| 20 | 0.0320 | 0.813 | Decorative panels, light covers | 0.45 |

| 22 | 0.0253 | 0.643 | Decorative trim, cosmetic applications | 0.36 |

| 24 | 0.0201 | 0.511 | Light decorative work, nameplates | 0.28 |

As PEKO Precision notes, for tight tolerance applications, always measure actual thickness with a caliper or micrometer before fabrication. Mill variations and coatings can shift nominal values slightly, and these deviations affect bend allowance calculations and final dimensions.

A pro tip for RFQs: list both the gauge and the actual thickness measurement. Specifying "16 ga aluminum (0.0508 in / 1.290 mm)" eliminates ambiguity and ensures everyone works from identical specifications. This simple practice prevents costly miscommunication between design, procurement, and fabrication teams.

With your alloy selected and thickness specified, the next step is understanding how these sheets get transformed into precise shapes. Cutting operations form the foundation of every fabrication project, and choosing the right method directly impacts edge quality, dimensional accuracy, and cost.

Cutting Methods for Aluminum Sheet Metal

You've got your alloy selected and thickness specified—now how do you actually cut aluminum sheet into usable parts? This question trips up many first-time fabricators because aluminum behaves differently than steel under cutting operations. Its high thermal conductivity disperses heat rapidly, its natural oxide layer affects edge quality, and its softer composition can cause issues with certain cutting methods. Understanding these nuances helps you choose the best way to cut aluminum sheet metal for your specific application.

The good news? Modern cutting technology gives you multiple options, each with distinct advantages. Whether you need intricate patterns with tight tolerances or simple straight cuts at high volume, there's an optimal method for your project.

Laser vs Waterjet vs Plasma for Aluminum Cutting

Three cutting technologies dominate professional aluminum fabrication shops. Your choice between them depends on material thickness, required precision, edge quality expectations, and budget constraints. Here's how each method performs on aluminum:

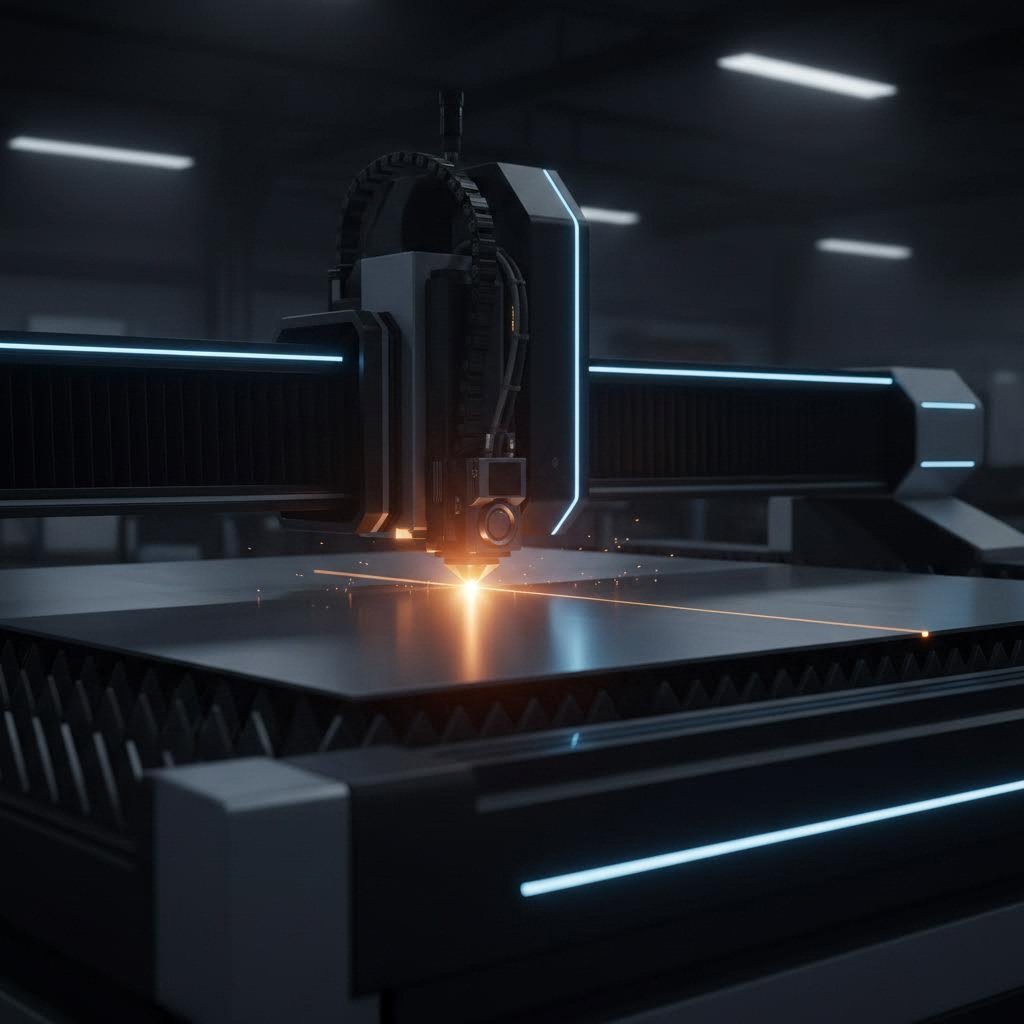

Laser Cutting focuses intense light energy to vaporize material along a programmed path. For aluminum sheets under 0.25 inches, laser cutting delivers exceptional precision with minimal kerf—the width of material removed during cutting. According to Wurth Machinery's technology comparison, laser excels when parts require clean edges, small holes, or intricate shapes.

- Pros: Superior precision for thin sheets, minimal post-processing needed, excellent for complex geometries, tight tolerances achievable

- Cons: Limited effectiveness on thick materials, higher reflectivity of aluminum requires fiber lasers rather than CO2 types, edge quality can suffer if parameters aren't optimized for aluminum's thermal properties

Waterjet Cutting uses high-pressure water mixed with abrasive garnet particles to cut through material. This cold-cutting process eliminates heat-affected zones entirely—a significant advantage when working with aluminum.

- Pros: No thermal distortion or warping, cuts any thickness effectively, preserves material properties near cut edges, handles reflective materials without issue

- Cons: Slower cutting speeds than thermal methods, higher operating costs due to abrasive consumption, wider kerf than laser cutting, secondary drying may be required

Plasma Cutting generates an electrical arc through compressed gas to melt and blast through conductive metals. For aluminum over 0.5 inches thick, plasma offers compelling speed and cost advantages.

- Pros: Fast cutting speeds on thick material, lower equipment and operating costs than laser or waterjet, effective on all conductive metals, portable options available for field work

- Cons: Larger heat-affected zone than other methods, rougher edge quality requiring secondary finishing, less precise on thin materials, not suitable for intricate detail work

Two additional methods round out the cutting toolkit:

Shearing remains the most economical approach for straight cuts. A shear press uses opposing blades to slice through aluminum sheets quickly and cleanly. If your parts feature only straight edges without internal cutouts, shearing delivers excellent value. However, it cannot produce curved profiles or interior features.

CNC Routing offers versatility across various thicknesses using rotating cutting tools. Routers handle everything from thin decorative panels to thick structural components, though cutting speeds are generally slower than thermal methods. This approach works particularly well when you need to cut an aluminum sheet with complex 2D profiles while maintaining tight tolerances.

Achieving Clean Cuts Without Burrs or Distortion

Understanding how to cut aluminum sheet metal properly requires attention to several factors that directly affect edge quality and dimensional accuracy.

Kerf Compensation is essential for precision parts. The kerf—material removed by the cutting process—varies by method:

- Laser cutting: 0.006-0.015 inches typical

- Waterjet cutting: 0.020-0.040 inches typical

- Plasma cutting: 0.050-0.150 inches typical

Your cutting program must offset tool paths by half the kerf width to achieve accurate final dimensions. Ignoring kerf compensation leads to undersized parts—a common mistake when learning how to cut an aluminum sheet with CNC equipment.

Oxide Layer Considerations affect cutting quality on aluminum. Unlike steel, aluminum instantly forms a thin aluminum oxide layer when exposed to air. This oxide melts at approximately 3,700°F while the base aluminum melts at only 1,220°F. During thermal cutting processes, this temperature differential can cause inconsistent melting and rough edges.

Experienced fabricators address this by:

- Using nitrogen or argon assist gas with laser cutting to minimize oxidation during the cut

- Adjusting power settings and feed rates specifically for aluminum's thermal properties

- Cleaning surfaces before cutting to remove heavy oxide buildup or contaminants

Heat Management distinguishes good aluminum cuts from poor ones. Aluminum's high thermal conductivity means heat spreads rapidly from the cut zone into surrounding material. Cutting too slowly allows excessive heat buildup, causing edge melting and distortion. Cutting too quickly may result in incomplete material removal and rough surfaces.

When deciding the best way to cut aluminum for your project, consider this decision framework:

- Thin sheets with complex patterns: Laser cutting

- Thick material or heat-sensitive applications: Waterjet cutting

- Thick conductive metals with moderate precision needs: Plasma cutting

- Straight cuts at high volume: Shearing

- Moderate complexity with mixed thicknesses: CNC routing

Many fabrication shops maintain multiple cutting technologies to match each job with its optimal process. Starting with the right cutting method sets up downstream operations—bending, forming, and joining—for success. Speaking of which, once your blanks are cut to size, transforming them into three-dimensional shapes requires understanding aluminum's unique bending characteristics.

Bending and Forming Aluminum Sheets

Your blanks are cut and ready—now comes the transformation from flat stock into functional three-dimensional components. Bending aluminum might seem straightforward, but treating it like steel is a recipe for cracked parts and wasted material. Aluminum is malleable, yes, but its unique mechanical properties demand specific techniques that account for springback, grain direction, and alloy behavior. Master these principles, and you'll consistently produce precise, crack-free bends.

What makes aluminum malleable enough for complex forming yet challenging to bend accurately? The answer lies in its crystalline structure and elastic recovery characteristics. Unlike steel, which tends to stay where you put it, aluminum "remembers" its original shape and partially springs back after the bending force releases. This aluminum flexibility is both an advantage—enabling intricate forming operations—and a challenge requiring careful compensation.

Calculating Springback Compensation for Accurate Bends

Springback is the invisible adversary in aluminum forming. You bend your part to 90 degrees, release the pressure, and watch it open up to 92 or 93 degrees. This elastic recovery happens because aluminum's outer fibers, stretched during bending, partially return toward their original state when unloaded.

How much compensation do you need? According to Xometry's design guidelines, springback angle can be estimated using this relationship:

Δθ = (K × R) / T

Where:

- K = Material constant (higher for harder alloys)

- R = Inside bend radius

- T = Material thickness

Harder tempers and larger radii produce more springback. A 6061-T6 part bent around a generous radius will spring back significantly more than soft 5052-H32 formed with a tighter radius.

Fabricators compensate for springback through several approaches:

- Overbending: Program the press brake to bend past the target angle by the expected springback amount

- Bottom bending or coining: Apply enough force to plastically deform the material through its full thickness, reducing elastic recovery

- Adaptive control systems: Modern CNC press brakes use real-time angle measurement sensors that automatically adjust ram depth to achieve target angles

For 5052 aluminum bending operations, expect 2-4 degrees of springback on typical 90-degree bends. Harder alloys like 6061-T6 may spring back 5-8 degrees or more. Always run test bends on sample material before committing to production quantities.

Understanding Bend Radius Requirements

Every aluminum alloy has a minimum bend radius—the tightest curve it can form without cracking. Push beyond this limit, and microscopic fractures on the outer surface quickly propagate into visible failures.

The minimum bend radius depends primarily on two factors: material ductility (measured as elongation percentage) and sheet thickness. According to forming specialists, soft annealed alloys like 3003-O can handle extremely tight bends approaching zero times the material thickness (0T), while high-strength 6061-T6 requires radii of 6T or greater to prevent cracking.

Grain direction adds another critical dimension. During rolling, aluminum sheets develop a pronounced grain structure with crystals aligned in the rolling direction. Bending parallel to this grain stresses the material along its weakest axis, significantly increasing crack risk. The professional approach? Orient bend lines perpendicular to the grain direction whenever possible, or at least at 45 degrees if perpendicular alignment isn't feasible.

Here's how common alloys compare in bendability:

- 3003-O: Minimum radius of 0-1T; excellent for tight bends and decorative applications

- 5052-H32: Minimum radius of 1-2T; exceptional bendability makes it the preferred choice for general fabrication

- 6061-T6: Minimum radius of 6T or greater; tends to crack at tight radii despite good overall strength

- 7075-T6: Minimum radius of 8T or greater; avoid bending when possible due to extreme crack sensitivity

The malleable aluminium characteristic that enables complex forming varies dramatically across these grades. When your design requires tight bends, specify 5052 or softer alloys. When strength is paramount and forming is minimal, 6061 or 7075 become viable options.

Forming Methods Beyond Simple Bends

Press brake bending handles most angular forming operations, but aluminum's formability enables more sophisticated shaping techniques:

Roll forming creates curved profiles by passing sheets through a series of roller dies. This progressive forming process produces consistent curved sections—think cylindrical housings, architectural curves, and tubular components—with excellent surface finish and dimensional control.

Deep drawing transforms flat blanks into cup-shaped or box-shaped components through controlled plastic deformation. The process pulls material into a die cavity, creating seamless containers, enclosures, and complex three-dimensional shapes. Aluminum's excellent ductility makes it well-suited for deep drawing, though proper lubrication and controlled blank holder pressure are essential to prevent wrinkling or tearing.

Stretch forming wraps aluminum sheets over a form die while applying tensile stress, producing large curved panels with minimal springback. Aircraft skins and automotive body panels frequently use this technique for smooth, compound-curved surfaces.

Critical DFM Rules for Aluminum Sheet Forming

Design for Manufacturability principles prevent forming failures before they happen. Following these guidelines during the design phase saves time, reduces scrap, and ensures your parts can actually be produced as specified.

- Minimum flange height: The bendable leg must be at least 4 times the material thickness plus the inside bend radius. For a 0.063-inch sheet with a 0.125-inch radius, minimum flange height is approximately 0.38 inches. Shorter flanges may not seat properly in the die or may slip during forming.

- Hole-to-bend distance: Keep holes and cutouts at least 2.5 times the material thickness plus the bend radius away from bend lines. Holes placed too close will distort into oval shapes as material stretches during bending.

- Bend relief requirements: When bends terminate at an edge or intersect with another feature, incorporate bend relief cuts—small notches at least equal to material thickness plus 1/32 inch. These reliefs prevent tearing at stress concentration points.

- Consistent bend radii: Standardize inside radii across your design whenever possible. Each unique radius requires different tooling, increasing setup time and cost. Common inside radii like 0.030, 0.062, or 0.125 inches align with standard press brake tooling.

- Bend sequence planning: Consider how each bend affects access for subsequent operations. Complex parts may require specific bending sequences to avoid collisions between formed flanges and press brake tooling.

- Grain direction notation: Call out critical bend orientations relative to grain direction on drawings. This ensures fabricators know which material orientation prevents cracking on your most demanding bends.

The K-factor—the ratio between the neutral axis location and sheet thickness—directly affects flat pattern calculations. According to manufacturing guidelines, aluminum typically uses K-factors between 0.30 and 0.45 depending on the ratio of bend radius to thickness and the forming method employed. Using inaccurate K-factors leads to parts that don't fit together properly after bending.

With your parts successfully cut and formed, the next challenge is joining them together. Aluminum welding presents its own unique requirements—higher thermal conductivity, a stubborn oxide layer, and a lower melting point all demand specialized techniques that differ fundamentally from steel welding.

Joining and Welding Aluminum Components

Your parts are cut and formed—now comes the challenge that separates skilled fabricators from amateurs. Aluminum welding requires a fundamentally different approach than steel, and treating these metals the same way guarantees poor results. The unique physical properties of aluminum create three distinct obstacles that every welder must overcome: rapid heat dissipation, a stubborn oxide layer, and a surprisingly low melting point that demands precise control.

Understanding these challenges transforms frustrating welds into consistent, high-quality joints. Whether you're joining thin enclosure panels or thick structural components, the principles remain constant—though the techniques vary significantly.

Why Aluminum Welding Requires Different Techniques Than Steel

Imagine pouring heat into a material that immediately tries to spread that energy everywhere except where you need it. That's aluminum welding in a nutshell. Three properties create the unique challenges you'll face:

High Thermal Conductivity means aluminum conducts heat approximately five times faster than steel. According to welding experts at YesWelder, this rapid heat dissipation creates a moving target—what worked at the start of your weld may cause burn-through halfway along the joint as the surrounding material heats up. You'll need to constantly adjust amperage or travel speed to compensate.

The Oxide Layer Problem presents perhaps the most frustrating obstacle. Pure aluminum melts at approximately 1,200°F (650°C), but the aluminum oxide layer that instantly forms on exposed surfaces melts at a staggering 3,700°F (2,037°C). Try welding without addressing this oxide, and you'll trap high-melting-point inclusions in your low-melting-point weld pool—a recipe for weak, porous joints.

Lower Melting Point combined with high thermal conductivity means you must move fast. The same amperage that barely heats steel will melt right through aluminum if you hesitate. This demands quick, confident torch movements and precise heat control that only comes with practice.

These factors explain why clean aluminum oxidation removal is non-negotiable before any welding operation. As Miller Welds emphasizes, a welding solutions specialist summed it up perfectly: "clean, clean, clean, clean… and clean." That's not exaggeration—it's the foundation of successful aluminum joining.

Pre-Weld Preparation: Cleaning Aluminum Oxide Properly

Before striking an arc, proper surface preparation determines whether you'll produce a strong joint or a contaminated failure. Cleaning aluminum oxide requires a systematic two-step approach:

- Step 1 - Degrease: Remove all oils, grease, and hydrocarbons using a solvent that leaves no residue. Avoid chlorinated solvents near welding areas—they can form toxic gases in the presence of an arc. Use cheesecloth or paper towels to wipe surfaces dry, as these porous materials absorb contaminants effectively.

- Step 2 - Mechanical Oxide Removal: Use a dedicated stainless steel wire brush to remove the oxide layer. This brush must be used only for aluminum to prevent cross-contamination from other metals. For heavy pieces or tight spaces, carbide burs work effectively, though watch for air tool exhaust that might introduce oils.

Critical sequence matters here: always degrease before brushing. Wire brushing dirty aluminum embeds hydrocarbons into the metal surface and transfers contaminants to the brush, making it unsuitable for future cleaning operations.

Storage practices prevent oxide problems before they start. Keep filler metals in sealed containers at room temperature, use cardboard tubes or original packaging to prevent surface damage, and store base metals in dry, climate-controlled environments when possible.

TIG vs MIG for Aluminum Sheet Applications

The mig vs tig welding debate for aluminum comes down to your priorities: maximum quality or production speed. Both processes work, but each excels in different situations.

TIG Welding Advantages

When quality matters most, AC TIG welding delivers superior results on aluminum sheet applications. The alternating current serves a dual purpose—the DCEP portion creates a cleaning action that breaks up aluminum oxides, while the DCEN portion focuses penetrating power into the base metal.

- Precise heat control: Foot pedal amperage adjustment lets you respond in real-time to heat buildup, preventing burn-through on thin materials

- Oxide management: AC balance settings allow fine-tuning between cleaning action and penetration

- Pulse capability: Pulse TIG prevents excessive heat input on thin sheet metal by alternating between high and low amperage

- Clean welds: Non-contact tungsten electrode minimizes contamination risk

The tig vs mig welding choice leans heavily toward TIG when welding 5052 aluminum or other thin sheet materials where appearance and joint integrity are critical. However, TIG demands more operator skill and takes longer to master.

MIG Welding Advantages

For production environments where speed matters, MIG welding aluminum offers compelling benefits:

- Faster deposition rates: Continuous wire feeding enables longer welds without stopping

- Lower learning curve: Easier to achieve acceptable results with less training

- Better for thick material: Higher heat input suits heavier gauges and structural components

- Cost-effective: Equipment and consumables generally cost less than TIG setups

MIG requires DCEP polarity, 100% argon shielding gas (your regular 75/25 CO2/argon mix won't work), and either a spool gun or specialized equipment with graphene liners to prevent soft aluminum wire from jamming.

Filler Metal Selection

Choosing between ER4043 and ER5356 filler alloys affects weld strength, appearance, and post-weld finishing options:

| Filler Alloy | Primary Alloying Element | Characteristics | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ER4043 | Silicon | Runs hotter, more fluid puddle, crack-resistant, shiny finish, softer wire harder to feed | General purpose, 6xxx series alloys, cosmetic welds |

| ER5356 | Magnesium | Higher tensile strength, more smoke/soot, runs cooler, stiffer wire feeds easier | Structural applications, 5xxx series alloys, anodized parts |

If you plan to anodize after welding, ER5356 provides a much closer color match. ER4043 tends to turn gray during the anodizing process, creating visible weld lines on finished parts.

Alternative Joining Methods

Not every aluminum assembly requires welding. Several alternative methods offer advantages for specific situations:

Rivets excel when joining dissimilar materials or when heat-affected zones are unacceptable. Aluminum rivets create strong mechanical joints without thermal distortion, making them ideal for sheet metal assemblies where welding would cause warping. Aircraft construction relies heavily on riveted aluminum assemblies for this reason.

Adhesive Bonding distributes stress across entire joint surfaces rather than concentrating loads at discrete points. Modern structural adhesives achieve impressive strength on thin aluminum sheets while adding vibration damping and sealing capabilities. This method works particularly well for decorative panels and enclosures where weld marks would be visible.

Mechanical Fastening using bolts, screws, or clinching provides easy disassembly for service access. While not as strong as welded joints in pure tension, mechanical fasteners allow field repair and component replacement that permanent joining methods cannot match.

Each joining method has its place in aluminum fabrication. The key lies in matching the method to your specific requirements for strength, appearance, serviceability, and cost. With your components joined into complete assemblies, surface finishing transforms raw fabricated parts into professional, durable products ready for their intended applications.

Surface Finishing Options for Fabricated Aluminum

Your components are cut, formed, and joined—but raw fabricated aluminum rarely goes directly into service. Surface finishing transforms functional parts into professional products that resist corrosion, wear beautifully, and meet the aesthetic demands of their applications. Whether you need an anodized aluminum sheet metal facade that weathers decades outdoors or a polished aluminum sheet enclosure that catches the eye, understanding your finishing options ensures you specify the right treatment for your project.

Surface preparation starts where welding left off. Before any finishing process, you must address the aluminum oxide layer that forms naturally on exposed surfaces. Proper cleaning removes contaminants, oils, and heavy oxide buildup that would otherwise compromise adhesion and appearance. This preparation step—often involving alkaline cleaners followed by deoxidizing treatments—determines whether your finish lasts years or fails within months.

Anodizing Types and When to Specify Each

Anodizing isn't a coating—it's an electrochemical transformation. The process submerges aluminum in an acid electrolyte bath while running electric current through the part. This controlled reaction grows the natural oxide layer into a highly structured, uniform coating that becomes part of the metal itself.

According to GD-Prototyping's technical analysis, the resulting anodic layer has a unique microscopic structure composed of millions of tightly packed hexagonal cells. Each cell contains a tiny pore—and these pores are the key to anodizing's coloring capability. Organic dyes absorb into the porous structure, creating vibrant metallic finishes that won't chip, peel, or flake because the color exists within the oxide layer itself.

Two anodizing specifications dominate fabrication applications:

Type II (Sulfuric Acid Anodizing) creates a moderate-thickness oxide layer of 5-25 microns. This process operates at room temperature with relatively mild parameters, producing a highly uniform porous structure ideal for decorative coloring. Anodized aluminum sheets treated with Type II offer excellent corrosion protection for normal environments—think consumer electronics, architectural elements, and automotive interior trim.

- Best for: Decorative applications requiring specific colors

- Best for: Parts needing good corrosion resistance without extreme wear requirements

- Best for: Applications where precise dimensional control matters (minimal buildup)

Type III (Hardcoat Anodizing) dramatically alters the process parameters—higher current density and near-freezing electrolyte temperatures force the oxide layer to grow thicker and denser. The result is a 25-75 micron coating with exceptional hardness and wear resistance. Approximately 50% of this coating penetrates the surface while 50% builds up on top, requiring dimensional compensation in part design.

- Best for: High-wear surfaces like sliding components and guides

- Best for: Parts exposed to abrasive conditions or repeated contact

- Best for: Harsh chemical or marine environments demanding maximum protection

One critical consideration: after growing the oxide layer, anodized parts require sealing. Hot deionized water or chemical sealants hydrate the oxide, swelling the pores closed. This sealing step locks in dye colors and dramatically improves corrosion resistance by preventing contaminants from entering the porous structure.

Powder Coating vs Anodizing for Aluminum Parts

While anodizing transforms the aluminum surface itself, powder coating applies a protective layer on top. This dry application process uses electrostatically charged powder particles that cling to grounded metal parts. Heat curing then melts and fuses the powder into a uniform, durable finish.

According to Gabrian's surface finishing comparison, powder coating offers several distinct advantages over traditional liquid paint:

- Thicker application: Single coats achieve 2-6 mils versus paint's 0.5-2 mils

- No solvents: Environmentally friendly with no volatile organic compounds

- Superior coverage: Electrostatic attraction wraps powder around edges and into recesses

- Vibrant colors: Broader color palette than anodizing, including textures and metallics

Powder coating services prove particularly valuable for industrial equipment, outdoor furniture, and architectural applications requiring specific color matching. The thicker coating provides excellent UV resistance and impact protection—though unlike anodizing, it can chip or scratch since it sits on top of the metal rather than becoming part of it.

When should you choose one over the other? Anodizing excels when you need heat dissipation (coatings insulate, anodizing doesn't), precise dimensions (thin buildup), or that distinctive metallic appearance only anodizing provides. Powder coat wins when you need exact color matching, maximum impact resistance, or lower finishing costs on complex geometries.

Mechanical Finishes for Aesthetic Control

Not every application requires electrochemical or applied coatings. Mechanical finishes alter the aluminum surface texture through physical processes, creating distinct appearances while often preparing surfaces for subsequent treatments.

Brushing drags abrasive pads or belts across aluminum surfaces in consistent linear patterns. The resulting fine parallel lines create a sophisticated satin appearance that hides minor scratches and fingerprints. Brushed finishes work beautifully on appliance panels, elevator interiors, and architectural trim where understated elegance matters.

Polishing progressively refines the surface using finer abrasives until achieving a mirror-like reflection. A polished aluminum sheet becomes highly reflective—ideal for decorative elements, lighting reflectors, and premium consumer products. However, polished surfaces show every fingerprint and scratch, requiring either protective coatings or acceptance of patina development.

Bead Blasting propels small spherical media against aluminum surfaces, creating a uniform matte texture. This process eliminates machining marks and minor surface defects while producing a consistent non-directional appearance. Bead blasted parts often proceed to anodizing, where the matte base texture creates distinctive satin-finished anodized aluminum with excellent glare reduction.

| Finish Type | Durability | Cost Level | Best Applications | Aesthetic Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type II Anodizing | Excellent corrosion resistance; moderate wear | Moderate | Consumer electronics, architectural elements, automotive trim | Metallic colors; slight sheen; reveals base texture |

| Type III Hardcoat | Exceptional wear and corrosion resistance | Higher | Sliding components, aerospace parts, marine hardware | Dark gray/black natural color; matte; industrial appearance |

| Powder Coating | Good impact and UV resistance; can chip | Lower to Moderate | Outdoor equipment, industrial machinery, architectural panels | Unlimited colors; smooth or textured; opaque coverage |

| Brushed | Moderate; scratches blend with pattern | Lower | Appliances, elevator panels, architectural trim | Satin linear pattern; hides fingerprints; refined appearance |

| Polished | Low; shows wear easily | Moderate to Higher | Decorative elements, reflectors, premium products | Mirror-like reflection; highly visible fingerprints |

| Bead Blasted | Moderate; uniform texture hides minor damage | Lower | Pre-anodize preparation, industrial components, lighting | Uniform matte; non-directional; reduced glare |

Combining mechanical and chemical finishes often produces the best results. A bead blasted and then anodized enclosure exhibits consistent matte color that resists fingerprints while providing excellent corrosion protection. A brushed and clear anodized panel maintains its refined linear texture while gaining durability for high-traffic environments.

With surface finishing complete, your fabricated aluminum transforms from raw manufacturing output into finished components ready for assembly and deployment. Understanding the cost factors that influence each step of this journey helps you make smarter decisions during the design phase—before expensive tooling and production commitments lock in your approach.

Cost Factors in Aluminum Sheet Fabrication

You've designed your part, selected your alloy, and specified your finish—but how much will it actually cost? Aluminum sheet fabrication pricing puzzles many engineers and procurement teams because so many variables influence the final number. Understanding these cost drivers before you finalize designs gives you leverage to make smarter choices that balance performance requirements against budget constraints.

The truth is, two seemingly similar parts can have dramatically different price tags based on material selection, design complexity, and production volume. Let's break down exactly what drives aluminum fabrication costs and how you can optimize each factor.

Hidden Cost Drivers in Aluminum Fabrication Projects

When you request quotes for custom aluminum products, several factors determine what you'll pay. Some are obvious; others catch buyers off guard.

Material Costs: Alloy Grade Matters More Than You Think

The aluminum sheet price varies dramatically based on alloy selection. According to Komacut's fabrication cost guide, different grades within each material type significantly affect both cost and performance. When you buy aluminum, expect to pay substantially more for high-performance alloys:

- 3003 aluminum: Most economical option; excellent for general-purpose applications

- 5052 aluminum: Moderate price increase over 3003; justified by superior corrosion resistance

- 6061 aluminum: Higher cost due to heat-treatability and structural capabilities

- 7075 aluminum: Premium pricing—often 3-4 times more expensive than 3003 due to aerospace-grade strength

Looking for cheap aluminum? Start with your actual performance requirements. Many projects specify 6061 or 7075 when 5052 or 3003 would perform identically in the intended application. This over-specification inflates material costs unnecessarily.

Market fluctuations add another layer of complexity. Aluminum commodity prices shift based on global supply, energy costs, and demand cycles. When shopping for aluminum material for sale, consider that quotes typically remain valid for limited periods—often 30 days—before material pricing requires re-evaluation.

Thickness Considerations

As Hubs' cost reduction guide notes, thicker sheets require more material and thus more processing time, resulting in higher costs. But the relationship isn't purely linear. Very thin gauges can actually cost more per part due to handling challenges, increased scrap rates, and slower processing speeds required to prevent distortion.

The sweet spot typically falls in medium gauges (14-18) where material is thick enough to handle efficiently but not so heavy that processing times balloon. When browsing aluminum sheets for sale, consider whether you truly need the thickest option or if a slightly thinner gauge meets your structural requirements.

Fabrication Complexity Factors

Every operation adds cost. The more you ask a fabricator to do, the higher your per-piece price:

- Number of bends: Each bend requires press brake setup and operator time. A part with twelve bends costs significantly more than one with three.

- Hole patterns: Complex hole layouts increase CNC programming time and cutting duration. Hundreds of small holes cost more than a few large ones.

- Tight tolerances: Demanding ±0.005" instead of ±0.030" requires slower processing, more inspections, and specialized equipment—all adding cost.

- Secondary operations: Countersinking, tapping, hardware insertion, and assembly steps each carry labor charges beyond basic fabrication.

Design complexity directly impacts cost, as noted by industry analysts. Consider the bend radius requirements and use specialized sheet metal design software to understand the limits of technology before committing to complex geometries.

Volume Economics

Perhaps obviously, economies of scale apply to sheet metal fabrication. Larger production runs result in lower per-unit costs. Why? Setup costs—programming CNC machines, configuring press brakes, creating fixtures—remain relatively constant whether you're making 10 parts or 1,000. Amortizing these fixed costs across larger quantities dramatically reduces per-piece pricing.

Consider this typical cost breakdown:

- 10 pieces: Setup costs dominate; per-unit price might be $50

- 100 pieces: Setup amortized; per-unit price drops to $15

- 1,000 pieces: Full volume efficiency; per-unit price reaches $8

If budget is constrained, consider ordering larger quantities less frequently rather than small batches repeatedly. The savings often justify carrying additional inventory.

Finishing Costs: The Often-Overlooked Budget Item

Post-processing—painting, powder coating, plating, or anodizing—can make parts cost significantly more than raw fabrication alone. Many project budgets underestimate finishing expenses, leading to unpleasant surprises. When browsing aluminum plate for sale, remember that the raw material represents only part of your total investment.

Type III hardcoat anodizing, for instance, costs considerably more than Type II decorative anodizing. Custom color matching for powder coating adds premiums over standard colors. Factor these finishing requirements into early budget estimates to avoid downstream sticker shock.

Design Strategies That Reduce Fabrication Expenses

Here's where Design for Manufacturability principles translate directly into cost savings. Smart design choices made early prevent expensive manufacturing challenges later.

- Optimize nesting efficiency: Design parts to nest efficiently on standard sheet sizes (48" × 96" or 48" × 120" are common). Odd shapes that waste material between parts increase your effective material cost.

- Standardize bend radii: Using consistent inside radii across your design means fewer tooling changes. Common radii like 0.030", 0.062", or 0.125" align with standard press brake tooling, eliminating custom tool charges.

- Minimize secondary operations: Every additional process—deburring, hardware insertion, spot welding—adds labor cost. Design features that eliminate post-processing steps deliver immediate savings.

- Specify appropriate tolerances: Tight tolerances where they're unnecessary waste money. Apply precision requirements only to functional features; leave non-critical dimensions with standard tolerances.

- Consider material availability: Choosing materials that are common or easily sourced reduces lead times and costs. Exotic alloys or unusual thicknesses may require minimum order quantities or extended delivery times.

- Design for automation: Parts that can be processed on automated equipment cost less than those requiring manual handling at each step.

- Reduce part count: Can two parts become one through clever design? Fewer unique components mean fewer setups, less assembly labor, and reduced inventory complexity.

The most significant cost reductions typically come from decisions made during initial design rather than from negotiating harder with fabricators. Engaging your manufacturing partner early—during design rather than after finalization—enables their DFM expertise to identify cost optimization opportunities before tooling and production commitments lock in expensive approaches.

With cost factors understood, you're equipped to make informed decisions balancing performance, quality, and budget. The next consideration is matching your project requirements to specific industry applications, where alloy selection, thickness specifications, and fabrication approaches align with sector-specific standards and certifications.

Industry Applications for Aluminum Sheet Fabrication

Understanding costs is valuable, but how do these principles translate into real-world applications? Different industries demand vastly different combinations of alloys, thicknesses, and fabrication techniques. What works perfectly for an HVAC duct fails miserably in an aircraft wing. What satisfies architectural requirements falls short of automotive structural demands. Matching your aluminum metal fabrication approach to industry-specific requirements ensures your aluminum parts perform reliably in their intended environment.

Is aluminum as strong as steel? Not in absolute terms—steel's tensile strength typically exceeds aluminum's by a significant margin. However, aluminum offers a superior strength-to-weight ratio, meaning you get more structural performance per pound of material. This distinction matters enormously in weight-sensitive applications where every gram counts.

Let's explore how five major industries leverage aluminum alloy sheet metal differently, each optimizing for their unique performance criteria and certification requirements.

Automotive Aluminum Fabrication Requirements and Certifications

The automotive sector has embraced aluminum aggressively in pursuit of fuel efficiency and emissions reduction. Body panels, structural components, and chassis elements increasingly rely on aluminum fabricated products that deliver steel-like strength at a fraction of the weight.

Primary alloys for automotive applications:

- 5052: Excellent formability makes it ideal for complex body panels, fenders, and interior components that require deep drawing or intricate shaping

- 6061: Heat-treatable strength suits structural components, suspension brackets, and load-bearing elements where tensile strength and fatigue resistance matter

According to MISUMI's alloy analysis, 6000 and 5000 series aluminum alloys are used in car bodies, chassis, wheels, and structural components to reduce weight, improve fuel efficiency, and enhance corrosion resistance.

Automotive aluminum parts manufacturing demands more than material knowledge—it requires rigorous quality systems. The IATF 16949 certification has become the global benchmark for automotive quality management. This standard goes beyond ISO 9001, incorporating automotive-specific requirements for defect prevention, continuous improvement, and supply chain traceability.

For chassis, suspension, and structural components where precision stamping meets aluminum sheet fabrication, manufacturers like Shaoyi (Ningbo) Metal Technology demonstrate what IATF 16949-certified production looks like in practice. Their approach—combining 5-day rapid prototyping with automated mass production and comprehensive DFM support—reflects the speed and quality demands that define modern automotive supply chains.

Typical automotive aluminum applications include:

- Hood and trunk lid panels (5052, 14-16 gauge)

- Door inner panels and reinforcements (6061, 12-14 gauge)

- Crash management structures (6061-T6, 10-12 gauge)

- Heat shields and thermal barriers (3003, 18-20 gauge)

Aerospace: Where Strength-to-Weight Ratios Define Success

No industry pushes aluminum performance harder than aerospace. When fuel represents a major operational cost and payload capacity directly affects profitability, every unnecessary ounce becomes unacceptable. This drives aerospace toward high-strength 2000 and 7000 series alloys that approach the tensile strength of many steels while weighing dramatically less.

7075 aluminum dominates structural aerospace applications for good reason. Its zinc-alloyed composition delivers tensile strength exceeding 83,000 psi—remarkable for aluminum and sufficient for airframe components, landing gear elements, and wing structures. According to industry specifications, 2000 and 7000 series alloys are widely used in aircraft frames, fuselages, landing gear, and engine components due to their high strength-to-weight ratio and fatigue resistance.

However, this strength comes with fabrication constraints:

- Limited weldability—mechanical fastening often replaces welding

- Poor formability—most shaping occurs through machining rather than bending

- Higher material costs—premium pricing reflects aerospace-grade purity requirements

Aerospace custom aluminum parts require meticulous documentation, material traceability from mill to finished component, and testing certifications that satisfy FAA and international aviation authorities. The fabrication processes themselves may appear similar to other industries, but the quality assurance wrapper around them becomes extraordinarily rigorous.

Architectural Applications: Durability Meets Aesthetics

Building facades, curtain walls, and architectural panels present a different challenge—components must look beautiful for decades while resisting weather, pollution, and UV exposure. This application space favors alloys that anodize well and resist atmospheric corrosion without demanding maximum strength.

3003 and 5005 aluminum dominate architectural applications. Both alloys accept anodizing beautifully, creating the protective and decorative finishes that define modern building exteriors. Their moderate strength proves sufficient for non-structural cladding, while excellent corrosion resistance ensures long service life.

Typical architectural specifications include:

- Curtain wall panels (anodized 5005, 14-18 gauge)

- Sunshade louvers (3003 with PVDF coating, 16-18 gauge)

- Decorative fascia and trim (anodized 3003, 18-22 gauge)

- Column covers and wraps (5005 with powder coating, 14-16 gauge)

Architects often specify exact anodizing colors using standards like Architectural Class I or Class II anodizing. These specifications define minimum coating thickness, colorfastness requirements, and testing protocols that ensure consistent appearance across large building projects where panels manufactured months apart must match visually.

HVAC and Industrial Equipment

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems consume vast quantities of aluminum sheet—primarily for ductwork, plenums, and air handling components. Here, the requirements shift toward formability, cost-effectiveness, and basic corrosion resistance.

3003 aluminum handles the majority of HVAC fabrication. Its excellent formability enables the complex folds, seams, and connections that ductwork demands. Moderate corrosion resistance proves adequate for indoor applications, while its lower cost compared to marine or aerospace grades keeps system costs manageable.

HVAC fabrication typically uses lighter gauges (18-24) since structural loads remain minimal. The key performance requirements center on airtight seams, smooth interior surfaces that minimize turbulence, and longevity sufficient to match building service life.

Industrial equipment presents broader requirements depending on specific applications:

- Machine guards and enclosures (5052 for outdoor equipment, 3003 for indoor)

- Control cabinets (6061 for structural rigidity, 16-14 gauge)

- Conveyor system components (6061 for wear resistance)

- Robotic cell guarding (3003 or 5052, perforated for visibility)

Matching Alloy Selection to Industry Standards

Electronics and thermal management applications demonstrate how aluminum's physical properties—not just its strength—drive material selection. The 6061 alloy appears frequently in this space, not for its structural capabilities but for its excellent machinability and thermal conductivity.

Electronic enclosures require precise machining for connector cutouts, ventilation patterns, and mounting features. The 6061-T6 temper machines cleanly with good surface finish, making it ideal for chassis that undergo extensive CNC operations after basic sheet forming.

Heat sinks exploit aluminum's thermal conductivity—roughly four times greater than steel—to dissipate heat from electronic components. Extruded or machined fins maximize surface area, while the base plate often originates from sheet stock. Here, thermal performance matters more than tensile strength, though adequate hardness prevents damage during handling and installation.

| Industry | Primary Alloys | Typical Gauges | Key Requirements | Critical Certifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automotive | 5052, 6061 | 10-16 | Formability, strength, weldability | IATF 16949 |

| Aerospace | 7075, 2024 | Varies widely | Maximum strength-to-weight | AS9100, NADCAP |

| Architectural | 3003, 5005 | 14-22 | Anodizing quality, aesthetics | AAMA specifications |

| HVAC | 3003 | 18-24 | Formability, cost-effectiveness | SMACNA standards |

| Electronics | 6061 | 14-18 | Machinability, thermal conductivity | UL listings, RoHS |

Understanding why tensile strength and hardness values matter comes down to matching material capabilities to functional demands. A 7075 aerospace bracket endures extreme cyclic loading that would fatigue weaker alloys. An architectural panel never sees those loads but must accept surface treatments that high-strength alloys resist. An electronic enclosure prioritizes heat transfer over either strength or finishing capability.

The aluminum parts manufacturing approach follows from these requirements. Aerospace emphasizes machining over forming due to alloy limitations. Automotive balances stamping efficiency with structural performance. Architecture prioritizes finishing quality. HVAC focuses on production speed and seam integrity. Electronics demands precise dimensional control for component fit.

Armed with industry-specific knowledge, the final consideration becomes selecting a fabrication partner capable of meeting your particular requirements. Certifications, equipment capabilities, and production flexibility vary dramatically across suppliers—and choosing the right partner often determines project success more than any technical specification.

Choosing an Aluminum Fabrication Partner

You've mastered alloys, gauges, cutting methods, and finishing options—but none of that knowledge matters if you partner with the wrong fabricator. The difference between a smooth production run and costly delays often comes down to selecting an aluminum fabricator with the right combination of certifications, equipment, and production flexibility. Whether you're searching for "metal fabrication near me" or evaluating suppliers across the globe, the evaluation criteria remain consistent.

Think of this decision as choosing a long-term collaborator rather than simply placing an order. The best aluminium fabrications result from partnerships where your manufacturer understands your industry, anticipates challenges, and adds value beyond basic metal processing. Here's how to identify those partners and avoid the ones that will cost you time and money.

Essential Certifications and Capabilities to Verify

Certifications tell you whether a fabricator has invested in documented quality systems—or simply claims good work without proof. According to TMCO's fabrication expertise guide, certifications demonstrate a commitment to consistent quality that random inspection cannot guarantee.

ISO 9001 certification establishes the baseline. This internationally recognized quality management standard requires documented processes, internal audits, corrective action procedures, and management review cycles. Any serious aluminium fabricator maintains ISO 9001 registration as a minimum credential. If a supplier lacks this basic certification, consider it a warning sign about their quality commitment.

IATF 16949 certification becomes mandatory for automotive applications. This automotive-specific standard layers additional requirements onto ISO 9001, including:

- Advanced product quality planning (APQP)

- Failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA)

- Production part approval process (PPAP)

- Statistical process control (SPC)

- Measurement system analysis (MSA)

For automotive chassis, suspension, and structural components, IATF 16949 certification isn't optional—it's table stakes. Partners like Shaoyi (Ningbo) Metal Technology exemplify this commitment, combining IATF 16949-certified quality systems with rapid prototyping and comprehensive DFM support that accelerates automotive supply chains.

AS9100 certification matters for aerospace applications, adding traceability and risk management requirements that the aviation industry demands. Specialized aluminium fabrication services for defense applications may require NADCAP accreditation for specific processes like welding or heat treatment.

Beyond certifications, verify actual equipment capabilities:

- Laser cutting capacity: What's the maximum sheet size? Thickness limitations? Do they run fiber lasers optimized for aluminum's reflectivity?

- Press brake tonnage: Higher tonnage handles thicker materials and longer bends. Verify their equipment matches your part requirements.

- Welding certifications: AWS D1.2 certification specifically covers structural aluminum welding. Ask about welder qualifications and procedure specifications.

- CNC machining: Multi-axis capability enables complex secondary operations in-house rather than requiring outside processing.

Evaluating Prototyping Speed and Production Scalability

The right custom aluminum fabricators serve you from first prototype through high-volume production without forcing supplier changes as quantities scale. This continuity preserves institutional knowledge about your parts and eliminates requalification delays.

Prototyping speed directly impacts your development timeline. When you need functional prototypes for testing, waiting six weeks defeats the purpose. Leading aluminum fabrication services offer rapid turnaround—some achieving 5-day delivery from order to shipment. This speed enables iterative design refinement without schedule penalties.

Equally important: does the prototyping process use production-intent methods? Laser-cut and brake-formed prototypes from the same equipment that will run production quantities provide far more valuable feedback than 3D-printed approximations or manually crafted samples.

Volume scalability requires examining both equipment capacity and supply chain resilience:

- Can they handle your anticipated volumes without capacity constraints?

- Do they maintain material inventory or operate hand-to-mouth on procurement?

- What's their ability to flex production schedules for demand spikes?

- Do they use automated material handling and robotic welding for consistent high-volume output?

DFM support separates transactional suppliers from true manufacturing partners. As industry experts note, the right fabricator doesn't just follow drawings—they help improve them. Engineering collaboration early in the process ensures manufacturability and cost efficiency before you commit to tooling.

Effective DFM review identifies:

- Features that increase cost without functional benefit

- Tolerances tighter than necessary for part function

- Bend sequences that create tooling access problems

- Material specifications that complicate procurement

- Finishing choices that add cost without performance value

Partners offering comprehensive DFM support—like those providing 12-hour quote turnaround with embedded engineering feedback—enable faster decision-making and optimized designs before production investment.

Quality Control and Communication Standards

According to quality control specialists, inspection isn't just about catching defects—it's about preventing them through systematic process control and early detection.

Dimensional inspection capabilities reveal quality commitment:

- Coordinate measuring machines (CMMs): Verify complex geometries to micron-level accuracy

- First article inspection (FAI) reports: Document compliance before production runs begin

- In-process inspection: Catch drift before it becomes scrap

- Final inspection protocols: Verify every critical dimension before shipment

Material traceability becomes essential for regulated industries. Can your supplier trace every component back to its original mill certification? This traceability enables rapid response if material issues emerge and satisfies regulatory requirements in aerospace, automotive, and medical applications.

Communication transparency keeps projects on track. The best partners provide:

- Clear project timelines with milestone updates

- Proactive notification of potential delays

- Engineering feedback during production if issues arise

- Accessible points of contact who understand your projects

Partner Evaluation Checklist

When evaluating potential aluminium fabrication services, work through this comprehensive criteria list:

- Certifications: ISO 9001 minimum; IATF 16949 for automotive; AS9100 for aerospace

- Equipment: Fiber laser cutting, CNC press brakes with adequate tonnage, certified welding stations

- Prototyping: Rapid turnaround (5-7 days); production-intent processes; engineering feedback included

- DFM support: Embedded engineering review; design optimization recommendations; fast quote turnaround

- Scalability: Capacity for your volume requirements; automated production capabilities; inventory management

- Quality control: CMM inspection; first article reporting; material traceability; in-process controls

- Finishing: In-house anodizing, powder coating, or established finishing partners

- Communication: Responsive contacts; project visibility; proactive updates

- Lead times: Realistic delivery commitments; on-time delivery track record

- Geographic considerations: Shipping costs; timezone alignment for communication; potential for site visits

Request references from customers in your industry. Ask about on-time delivery performance, quality consistency, and responsiveness when problems arise. A fabricator's reputation among peers reveals more than any sales presentation.

The aluminum sheet fabrication journey—from raw metal to finished part—succeeds or fails based on the decisions outlined throughout this guide. Select the right alloy for your application. Specify appropriate gauges using the correct material standards. Choose cutting and forming methods suited to your geometry. Apply finishing treatments matched to your environment. And partner with a fabricator whose capabilities, certifications, and communication style align with your project demands. Master these elements, and you transform aluminum sheets into reliable, high-performing components that serve their intended purpose for years to come.

Frequently Asked Questions About Aluminum Sheet Fabrication

1. Is aluminum fabrication expensive?

Aluminum fabrication costs vary significantly based on several factors. Material costs differ by alloy grade—7075 aerospace aluminum costs 3-4 times more than general-purpose 3003. Fabrication complexity adds expense through multiple bends, tight tolerances, and secondary operations. Volume economics play a major role: setup costs spread across larger production runs dramatically reduce per-piece pricing. A part costing $50 each at 10 pieces might drop to $8 each at 1,000 pieces. Design for Manufacturability principles—like standardizing bend radii and optimizing nesting—can reduce costs by 15-30% without sacrificing performance.

2. Is aluminum easy to fabricate?

Aluminum is generally easier to fabricate than many metals due to its excellent formability and machinability. Alloys like 5052 bend readily without cracking, while 6061 machines cleanly with good surface finish. However, aluminum presents unique challenges: it requires larger bend radii than steel to prevent cracking, its high thermal conductivity demands different welding techniques, and the oxide layer must be removed before welding. Choosing the right alloy for your fabrication method is crucial—5052 excels at bending while 7075 should primarily be machined rather than formed.

3. What's 1 lb of aluminum worth?

Primary aluminum currently sells around $1.17 per pound, while scrap aluminum ranges from $0.45 to over $1.00 per pound depending on grade and cleanliness. However, fabricated aluminum products carry significantly higher value due to processing costs. Sheet aluminum pricing depends on alloy grade, thickness, and market conditions. When purchasing aluminum sheets for fabrication projects, expect to pay premiums for specialty alloys like 7075 (aerospace) or marine-grade 5052. Quotes typically remain valid for 30 days before requiring re-evaluation due to commodity price fluctuations.

4. What is the best aluminum alloy for sheet metal fabrication?

5052 aluminum is widely considered the best choice for general sheet metal fabrication. It offers excellent bendability with minimal springback, superior corrosion resistance for outdoor and marine applications, and outstanding weldability. The H32 temper provides enough ductility for tight bends while maintaining adequate strength. For structural applications requiring heat-treatability, 6061-T6 delivers higher tensile strength but requires larger bend radii. 3003 offers the most economical option for non-demanding applications like HVAC ductwork, while 7075 suits aerospace applications where maximum strength outweighs formability concerns.

5. How do I choose the right aluminum fabrication partner?

Evaluate potential partners based on certifications, equipment capabilities, and production flexibility. ISO 9001 certification establishes quality baselines, while IATF 16949 is mandatory for automotive applications. Verify laser cutting capacity, press brake tonnage, and welding certifications match your requirements. Assess prototyping speed—leading fabricators offer 5-day turnaround with production-intent methods. Comprehensive DFM support indicates a true manufacturing partner who optimizes designs before production. Request references from customers in your industry and examine on-time delivery track records. Partners like IATF 16949-certified manufacturers offering rapid prototyping and 12-hour quote turnaround demonstrate the responsiveness modern supply chains demand.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —