Quarter Panel Stamping Automotive Guide: Class A Precision & Process

TL;DR

Quarter panel stamping automotive processes represent the pinnacle of metal forming, transforming flat sheet metal into the complex, Class A curved surfaces that define a vehicle's rear architecture. This high-precision manufacturing method involves sequential operations—blanking, deep drawing, trimming, and flanging—typically executed on tandem or transfer press lines. For engineers and procurement professionals, success hinges on mastering deep-draw mechanics, controlling springback in High-Strength Low-Alloy (HSLA) steel or aluminum, and adhering to rigorous surface quality standards to eliminate visible defects.

The Quarter Panel: A 'Class A' Engineering Challenge

In automotive design, the quarter panel is more than just a sheet of metal; it is a critical "Class A" surface, meaning it is highly visible to the customer and must be aesthetically flawless. Unlike internal structural brackets, the quarter panel defines the vehicle's visual continuity, bridging the gap between the rear doors, the roofline (C-pillar), and the trunk. It must integrate complex features such as the wheel arch, fuel filler pocket, and taillight mountings while maintaining a smooth, aerodynamic contour.

Manufacturing these panels is an engineering paradox: they must be stiff enough to provide structural integrity and dent resistance, yet the metal must be ductile enough to stretch into deep, complex shapes without tearing. The transition from vintage two-piece designs to modern "uni-side" panels (where the quarter panel and roof rail are stamped as one unit) has exponentially increased the difficulty of the deep-drawing process. Any imperfection—even a few microns deep—is unacceptable on a Class A surface.

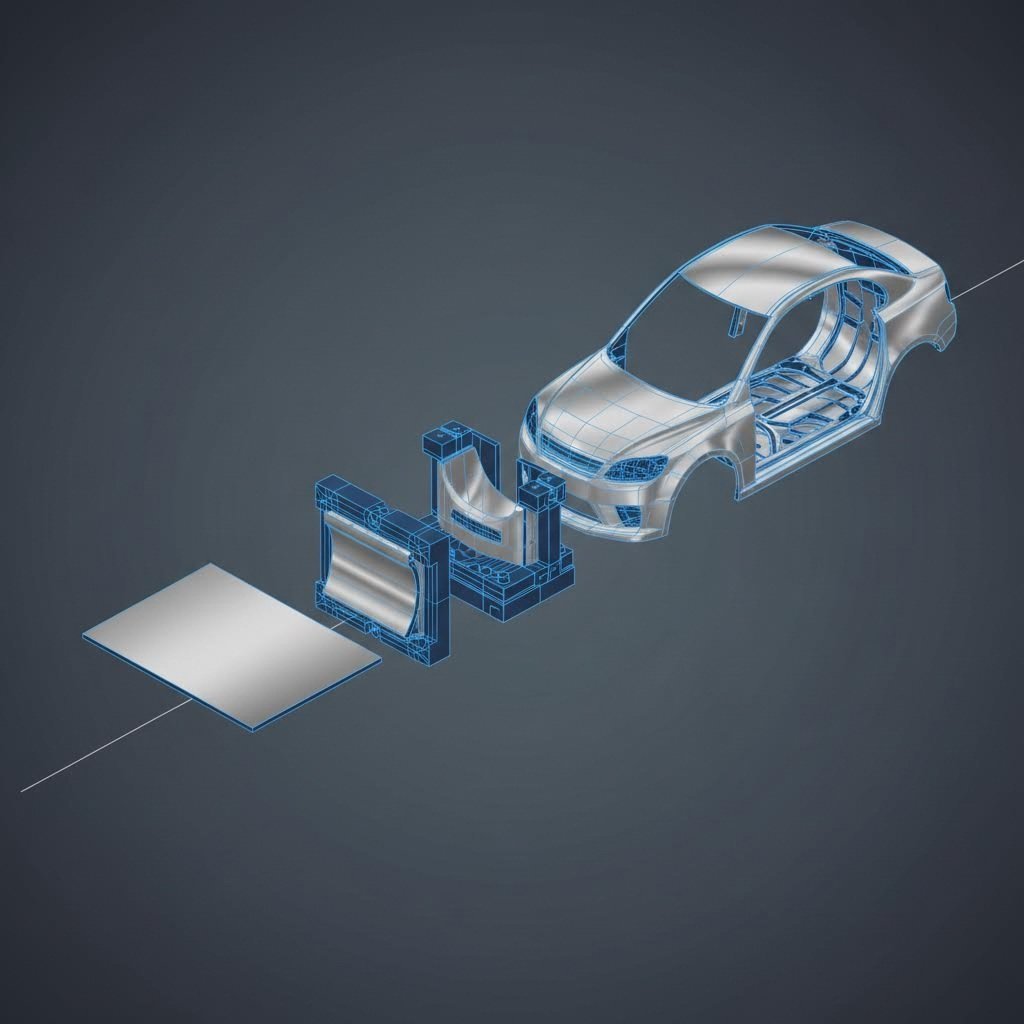

The Manufacturing Process: From Coil to Component

The journey of a quarter panel from a coil of raw metal to a finished body component involves a precise choreography of high-tonnage physics. While specific lines vary, the core quarter panel stamping automotive workflow generally follows four critical stages.

1. Blanking and Tailored Blanks

The process begins with blanking, where the raw coil is cut into a flat, roughly shaped sheet called a "blank." Modern manufacturing often utilizes "tailor-welded blanks" (TWB), where different grades or thicknesses of steel are laser-welded together before stamping. This allows engineers to place stronger, thicker metal in crash-critical zones (like the C-pillar) and thinner, lighter metal in low-stress areas, optimizing weight without compromising safety.

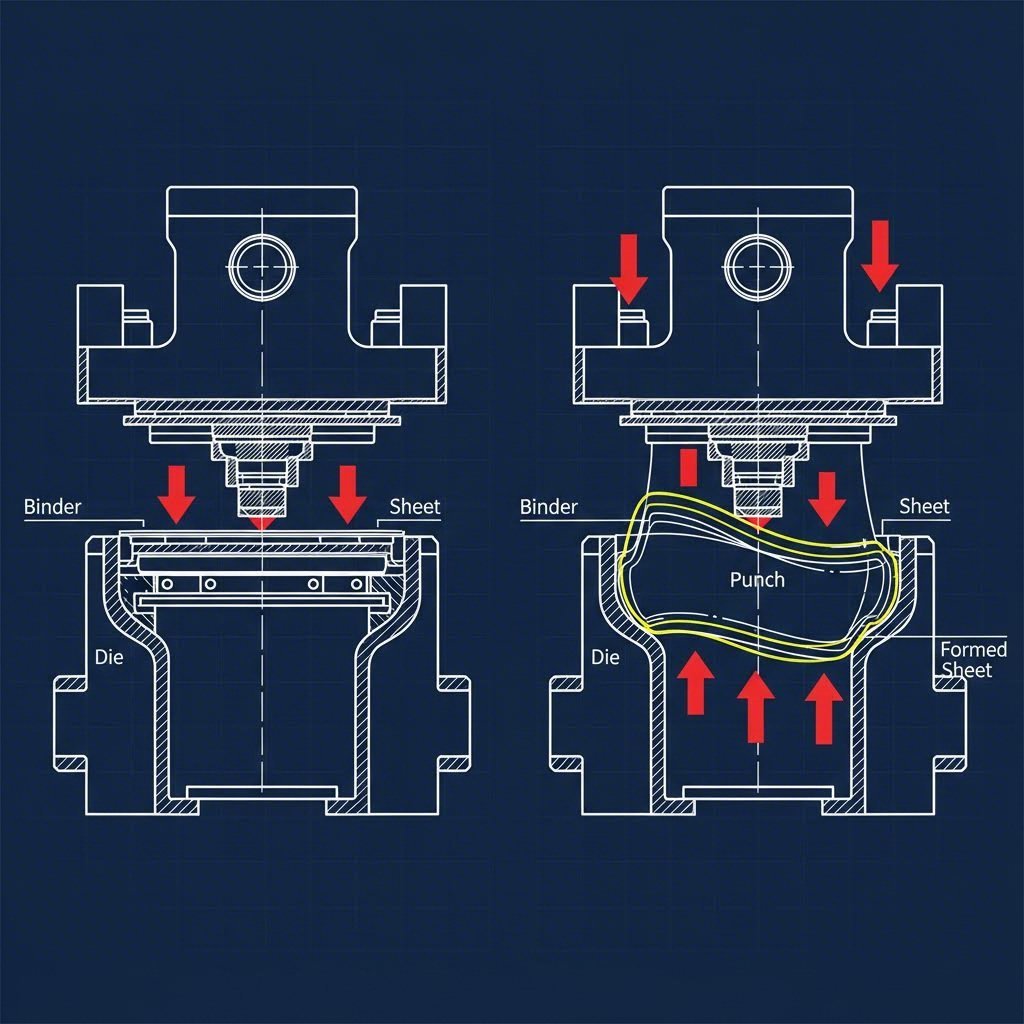

2. Deep Drawing (The Forming Stage)

This is the most critical operation. The flat blank is placed into a draw die, and a massive press (often exerting 1,000 to 2,500 tons of force) pushes a punch against the metal, forcing it into a die cavity. The metal flows plastically to take the 3D shape of the quarter panel. The perimeter of the blank is held by a "binder," which applies precise pressure to control the flow of metal. Too much binder pressure causes the metal to split; too little causes it to wrinkle.

3. Trimming and Piercing

Once the general shape is formed, the panel moves to trimming dies. Here, the excess scrap metal around the edges (the "addendum" used for gripping during drawing) is sheared off. Simultaneously, piercing operations cut precise holes for the fuel filler door, side marker lights, and antenna mounts. Precision is paramount here; a misalignment of even a millimeter can lead to panel gaps during final assembly.

4. Flanging and Restriking

The final stages involve bending the edges of the panel to create flanges—the surfaces where the quarter panel will be welded to the inner wheelhouse, trunk floor, and roof. A "restrike" operation may be used to sharpen character lines and radius details that weren't fully formed during the initial draw.

Critical Defects & Quality Control

Because the quarter panel is a Class A surface, quality control goes far beyond simple dimensional checks. Manufacturers fight a constant battle against microscopic surface defects that become glaringly obvious once the car is painted.

The "Stoning" Test and Zebra Lighting

To detect "lows" (depressions) or "highs" (bumps) that are invisible to the naked eye, inspectors use a "stoning" technique. They rub a flat abrasive stone across the stamped panel; the stone scratches the high spots and skips over the low spots, creating a visual map of surface topography. Automated inspection tunnels equipped with "zebra striping" lights also scan panels, using the distortion of reflected light stripes to identify surface waves or "orange peel" texture issues.

Springback and Compensation

When the press lifts, the metal naturally tries to return to its original flat shape—a phenomenon known as springback. This is especially prevalent in high-strength steels and aluminum. To counteract this, die engineers use simulation software (like AutoForm) to design the die surface with "compensation," effectively over-bending the metal so that when it springs back, it settles into the correct final geometry.

Material Science: Steel vs. Aluminum

The push for fuel efficiency has driven a major shift in materials. While mild steel was once the standard, modern quarter panels are increasingly stamped from High-Strength Low-Alloy (HSLA) steel or aluminum alloys (5xxx and 6xxx series) to reduce vehicle weight.

| Feature | HSLA Steel | Aluminum (5xxx/6xxx) |

|---|---|---|

| Weight | Heavy | Light (up to 40% savings) |

| Formability | Good to Excellent | Lower (prone to tearing) |

| Springback | Moderate | Severe (requires advanced compensation) |

| Cost | Low | High |

Stamping aluminum quarter panels requires distinct lubrication strategies and often necessitates specialized coatings on the die surface to prevent "galling" (aluminum sticking to the tool). Additionally, aluminum scrap must be carefully segregated from steel scrap in the press shop to prevent cross-contamination.

Tooling Strategies and Sourcing Considerations

The dies required for quarter panels are massive, often cast from iron and weighing several tons. Developing these tools involves "die face engineering," where the addendum and binder surfaces are designed to manage metal flow. For high-volume production, these dies are typically hardened and coated with chrome or physical vapor deposition (PVD) layers to withstand millions of cycles.

However, not every component requires a 2,000-ton transfer line. For associated structural reinforcements, brackets, or chassis parts like control arms, manufacturers often rely on more agile partners. Companies like Shaoyi Metal Technology specialize in bridging the gap between rapid prototyping and mass production. With IATF 16949 certification and press capabilities up to 600 tons, they provide the precision necessary for these critical sub-components, ensuring the structural foundation of the vehicle matches the Class A excellence of the exterior skin.

Conclusion: The Future of Body Panels

Automotive quarter panel stamping remains one of the most demanding disciplines in manufacturing. As vehicle designs evolve toward sharper character lines and lighter materials, the margin for error shrinks. The future lies in "smart stamping," where press lines automatically adjust binder force in real-time based on sensor feedback, and digital twin technology predicts defects before a single blank is cut. For automakers, mastering this process is not just about shaping metal; it's about defining the brand's visual signature on the road.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the main steps in the stamping method?

The automotive stamping process generally consists of four to seven main steps depending on complexity. The primary sequence is: Blanking (cutting the raw shape), Deep Drawing (forming the 3D geometry), Trimming/Piercing (removing excess metal and cutting holes), and Flanging/Restriking (forming edges and sharpening details). Additional steps like bending or coining may be included for specific features.

2. What is the difference between a front fender and a rear quarter panel?

A front fender is the body panel covering the front wheel, typically bolted onto the chassis for easy replacement. A rear quarter panel, however, is usually welded directly to the vehicle's unibody structure, extending from the rear door to the taillights. Because it is a welded structural component, replacing a quarter panel is significantly more labor-intensive and expensive than replacing a bolted front fender.

3. What defines a 'Class A' surface in stamping?

A Class A surface refers to the visible outer skin of the vehicle that must be free of any aesthetic defects. In stamping, this means the panel must have perfect curvature continuity and be free from sink marks, dings, ripples, or "orange peel" texture. These surfaces are subject to the strictest quality control measures, including zebra light inspection and stoning tests.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —