Strategic Material Selection for Automotive Forming Dies

TL;DR

Strategic material selection for automotive forming dies is a critical engineering decision that extends beyond initial cost and hardness. The optimal choice balances performance against the total cost of ownership, involving a detailed evaluation of materials like tool steels (e.g., D2), carbon steels, and advanced powder metallurgy (PM) alloys. Key properties such as wear resistance, toughness, and thermal stability are paramount to withstand the extreme conditions of forming, especially with advanced high-strength steels (AHSS).

Beyond Hardness & Cost: A Strategic Approach to Die Material Selection

In manufacturing, a common but costly mistake is selecting a material for a forming die based primarily on its hardness rating and upfront price per kilogram. This oversimplified approach often fails catastrophically in high-demand automotive applications, leading to a cascade of hidden costs from premature die failure, production downtime, and poor part quality. A more sophisticated method is required—one that evaluates the material's performance within the entire production system and focuses on the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO).

Strategic material selection is a multi-factor analysis aimed at minimizing TCO by considering the die's entire lifecycle. This includes the initial material and fabrication costs plus lifetime operating expenses like maintenance, unscheduled repairs, and the immense cost of production stoppages. A material mismatch can have devastating financial consequences. For example, industry data shows a single hour of unplanned downtime for a major automotive manufacturer can cost millions in lost output and logistical chaos. A cheaper die that fails frequently is far more expensive in the long run than a premium one that delivers consistent performance.

The principle becomes clear with a direct comparison. Consider a conventional D2 tool steel die versus one made from a higher-grade Powder Metallurgy (PM) steel for a high-volume stamping job. While the PM steel's initial cost might be 50% higher, its superior wear resistance could extend its life by four to five times. This longevity drastically reduces the number of downtime events for die replacement, leading to significant savings. As detailed in a TCO analysis by Jeelix, a premium material can result in a 33% lower total cost of ownership, proving that a higher initial investment often yields a far greater long-term return.

Adopting a TCO model requires a shift in mindset and process. It necessitates establishing a cross-functional team that includes engineering, finance, and production to evaluate material choices holistically. By framing the decision around the long-term cost per part rather than the short-term price per kilogram, manufacturers can transform their tooling from a recurring expense into a strategic, value-creating asset that enhances reliability and profitability.

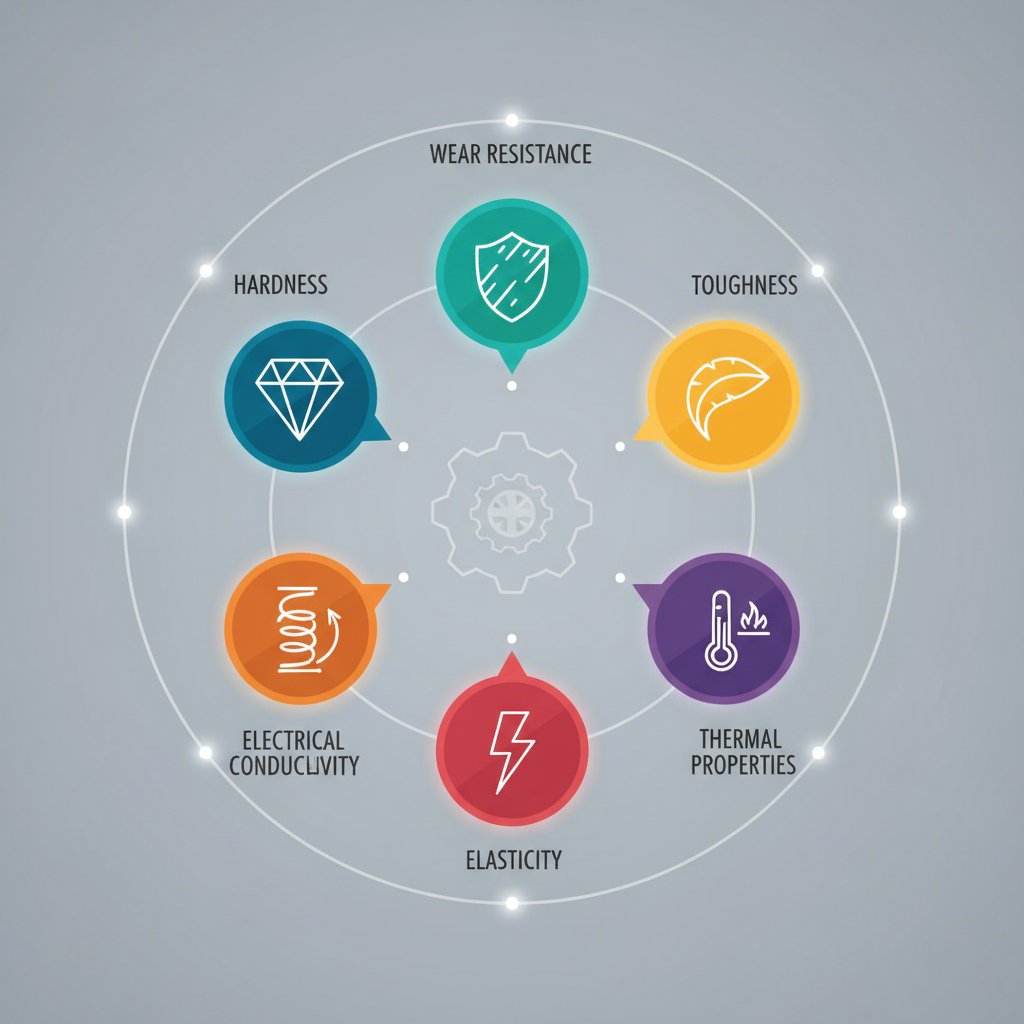

The Seven Pillars of Die Material Performance

To move beyond simplistic selection criteria, a structured evaluation based on a material's core performance attributes is essential. These seven interconnected pillars, adapted from a comprehensive framework, provide a scientific foundation for choosing the right material. Understanding the trade-offs between these properties is the key to engineering a successful and durable forming die.

1. Wear Resistance

Wear resistance is a material's ability to withstand surface degradation from mechanical use and is often the primary factor determining a die's lifespan in cold-work applications. It manifests in two key forms. Abrasive wear occurs when hard particles in the workpiece, like oxides, scratch and gouge the die surface. Adhesive wear, or galling, happens under intense pressure when microscopic welds form between the die and workpiece, tearing away material when the part is ejected. A high volume of hard carbides in the steel's microstructure is the best defense against both.

2. Toughness

Toughness is a material's capacity to absorb impact energy without fracturing or chipping. It is the die's ultimate safeguard against sudden, catastrophic failure. There is a critical trade-off between hardness and toughness; increasing one almost always decreases the other. A die for a complex part with sharp features requires high toughness to prevent chipping, while a simple coining die may prioritize hardness. Material purity and a fine grain structure, often achieved through processes like Electro-Slag Remelting (ESR), significantly enhance toughness.

3. Compressive Strength

Compressive strength is the material's ability to resist permanent deformation under high pressure, ensuring the die cavity maintains its precise dimensions over millions of cycles. For hot-work applications, the crucial measure is hot strength (or red hardness), as most steels soften at elevated temperatures. Hot-work tool steels like H13 are alloyed with elements like molybdenum and vanadium to maintain their strength at high operating temperatures, preventing the die from gradually sagging or sinking.

4. Thermal Properties

This pillar governs how a material behaves under rapid temperature changes, which is critical in hot forming and forging. Thermal fatigue, seen as a network of surface cracks called "heat checking," is a leading cause of failure in hot-work dies. A material with high thermal conductivity is advantageous as it dissipates heat from the surface more quickly. This not only allows for shorter cycle times but also reduces the severity of temperature swings, extending the die's life.

5. Manufacturability

Even the most advanced material is useless if it cannot be efficiently and accurately shaped into a die. Manufacturability encompasses several factors. Machinability refers to how easily the material can be cut in its annealed state. Grindability is crucial after heat treatment when the material is hard. Finally, weldability is vital for repairs, as a reliable weld can save a company from the massive expense and downtime of fabricating a new die.

6. Heat Treatment Response

Heat treatment unlocks a material's full performance potential by creating the ideal microstructure, typically tempered martensite. A material's response determines its final combination of hardness, toughness, and dimensional stability. Key indicators include predictable dimensional stability during treatment and the ability to achieve consistent hardness from surface to core (through-hardening), which is especially important for large dies.

7. Corrosion Resistance

Corrosion can degrade die surfaces and initiate fatigue cracks, particularly when dies are stored in humid environments or used with materials that off-gas corrosive substances. The primary defense is chromium, which, at levels above 12%, forms a passive protective oxide layer. This is the principle behind stainless tool steels like 420SS, which are often used where a pristine surface finish is mandatory.

Guide to Common & Advanced Die Materials

The selection of a specific alloy for an automotive forming die depends on a careful balance of the performance pillars against application demands. The most common materials are ferrous alloys, ranging from conventional carbon steels to highly advanced powder metallurgy grades. The "best" material is always application-specific, and a deep understanding of each family's characteristics is crucial for making an informed choice. For businesses seeking expert guidance and manufacturing of high-precision tooling, specialist firms like Shaoyi (Ningbo) Metal Technology Co., Ltd. offer comprehensive solutions, from rapid prototyping to mass production of automotive stamping dies using a wide array of these advanced materials.

Carbon Steels are iron-carbon alloys that offer a cost-effective solution for lower-volume or less demanding applications. They are categorized by carbon content: low-carbon steels are soft and easily machined but lack strength, while high-carbon steels offer better wear resistance but are more difficult to work with. Finding the right balance between performance and manufacturing cost is key.

Tool Steels represent a significant step up in performance. These are high-carbon steels alloyed with elements like chromium, molybdenum, and vanadium to enhance specific properties. They are broadly classified by their intended operating temperature. Cold-work tool steels like D2 and A2 are known for high wear resistance and hardness at ambient temperatures. Hot-work tool steels, such as H13, are engineered to retain their strength and resist thermal fatigue at elevated temperatures, making them ideal for forging and die casting.

Stainless Steels are used when corrosion resistance is a primary concern. With high chromium content, martensitic grades like 440C can be heat-treated to high hardness levels, while still offering good corrosion resistance. They are often chosen for applications in the medical or food processing industries but also find use in automotive tooling where environmental exposure is a factor.

Specialty & Nickel-Based Alloys, such as Inconel 625, are designed for the most extreme environments. These materials offer exceptional strength and resistance to oxidation and deformation at very high temperatures where even hot-work tool steels would fail. Their high cost reserves them for the most demanding applications.

Powder Metallurgy (PM) Tool Steels represent the cutting edge of die material technology. Produced by consolidating fine metal powders rather than casting large ingots, PM steels have a remarkably uniform microstructure with small, evenly distributed carbides. As highlighted in case studies from AHSS Insights, this eliminates the large, brittle carbide networks found in conventional steels. The result is a material that provides a superior combination of wear resistance and toughness, making PM steels an excellent choice for stamping high-strength automotive components where conventional tool steels like D2 might fail prematurely.

| Material Type | Key Properties | Common Grades | Pros | Cons | Ideal Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Steels | Good machinability, low cost | 1045, 1050 | Inexpensive, widely available, easy to machine | Low wear resistance, poor hot strength | Low-volume production, forming mild steels |

| Cold-Work Tool Steels | High hardness, excellent wear resistance | A2, D2 | Long life in abrasive conditions, holds a sharp edge | Lower toughness (brittle), poor for hot work | High-volume stamping, blanking, trimming AHSS |

| Hot-Work Tool Steels | High hot strength, good toughness, thermal fatigue resistance | H13 | Maintains hardness at high temperatures, resists heat checking | Lower abrasive wear resistance than cold-work steels | Forging, extrusion, die casting |

| Powder Metallurgy (PM) Steels | Superior blend of wear resistance and toughness | CPM-10V, Z-Tuff PM | Exceptional performance, resists chipping and wear simultaneously | High material cost, can be challenging to machine | Demanding applications, forming ultra-high-strength steels |

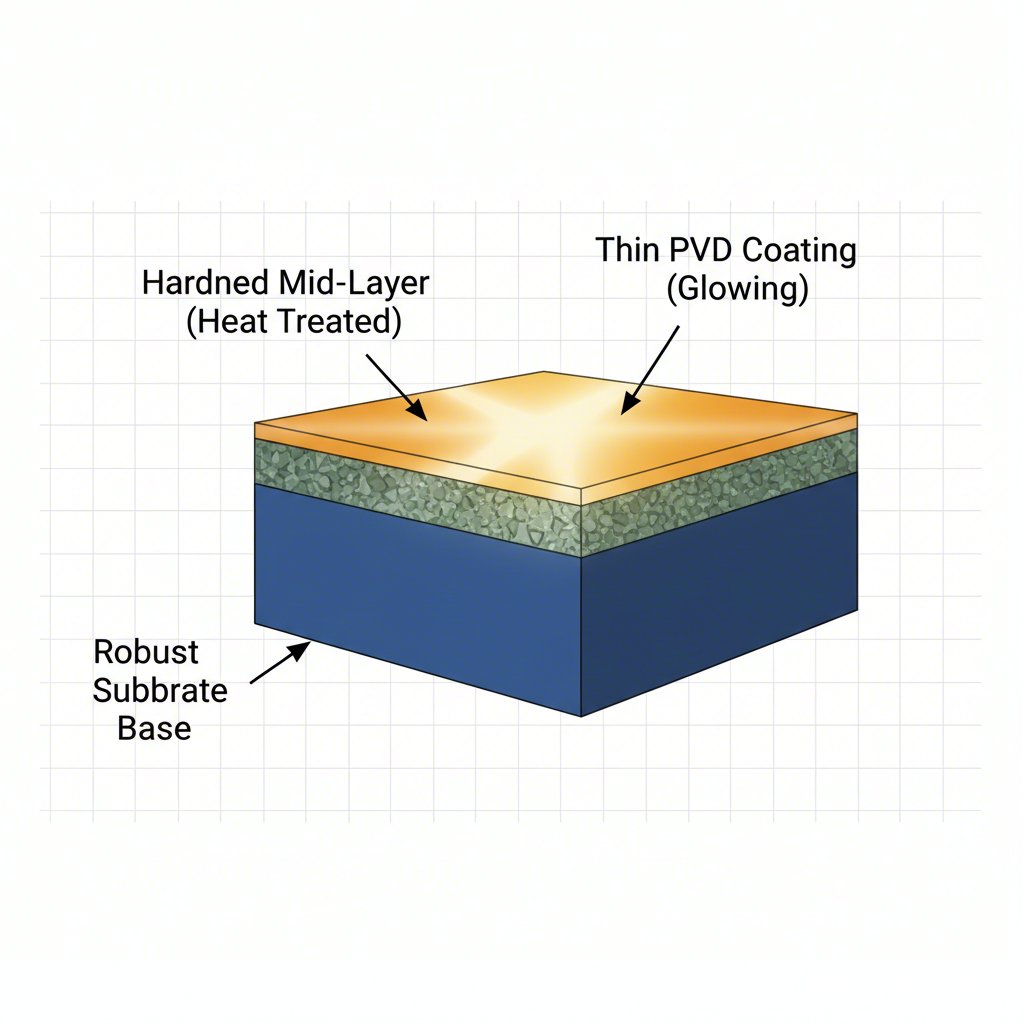

Performance Multipliers: Coatings, Heat Treatment & Surface Engineering

Relying on the base material alone is a limited strategy. True performance breakthroughs are achieved by viewing the die as an integrated system, where the substrate, its heat treatment, and a tailored surface coating work in synergy. This "performance trinity" can multiply a die's lifespan and effectiveness far beyond what the substrate could achieve on its own.

The substrate is the die's foundation, providing the core toughness and compressive strength to withstand forming forces. However, a common mistake is assuming a high-tech coating can compensate for a weak substrate. Hard coatings are incredibly thin (typically 1-5 micrometers) and require a solid base. Applying a hard coating to a soft substrate is like placing glass on a mattress—the base deforms under pressure, causing the brittle coating to fracture and peel away.

Heat treatment is the process that unlocks the substrate's potential, developing the necessary hardness to support the coating and the toughness to prevent fracture. This step must be compatible with the subsequent coating process. For example, Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) occurs at temperatures between 200°C and 500°C. If the substrate's tempering temperature is lower than this, the coating process will soften the die, severely compromising its strength.

Surface engineering applies a functional layer that delivers properties the bulk material cannot, such as extreme hardness or low friction. Diffusion treatments like Nitriding infuse nitrogen into the steel's surface, creating an integral, ultra-hard case that won't peel or delaminate. Deposited coatings like PVD and Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) add a distinct new layer. PVD is preferred for precision dies due to its lower processing temperatures, which minimize distortion.

Selecting the right coating depends on the dominant failure mode. The table below matches common failure mechanisms with recommended coating solutions, a strategy that turns surface engineering into a precise problem-solving tool.

| Dominant Failure Mode | Recommended Coating Type | Mechanism & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Abrasive Wear / Scratching | TiCN (Titanium Carbo-Nitride) | Offers extreme hardness to provide exceptional protection against hard particles in the workpiece. |

| Adhesive Wear / Galling | WC/C (Tungsten Carbide/Carbon) | A Diamond-Like Carbon (DLC) coating that provides intrinsic lubricity, preventing material pickup, especially with aluminum or stainless steel. |

| Heat Checking / Hot Wear | AlTiN (Aluminum Titanium Nitride) | Forms a stable, nanoscale layer of aluminum oxide at high temperatures, creating a thermal barrier that protects the die. |

A final, crucial recommendation is to always complete die tryouts and necessary adjustments before applying the final coating. This prevents the costly removal of a newly applied surface during the final tuning stages and ensures the system is optimized for production.

Diagnosing & Mitigating Common Die Failure Modes

Understanding why dies fail is as important as selecting the right material. By identifying the root cause of a problem, engineers can implement targeted solutions, whether through material upgrades, design changes, or surface treatments. The most common failure modes in automotive forming dies are wear, plastic deformation, chipping, and cracking.

Wear (Abrasive and Adhesive)

Problem: Wear is the gradual loss of material from the die surface. Abrasive wear appears as scratches caused by hard particles, while adhesive wear (galling) involves the transfer of material from the workpiece to the die, leading to scoring on the part surface. This is a primary concern when forming AHSS, where high contact pressures exacerbate friction.

Solution: To combat abrasive wear, select a material with high hardness and a large volume of hard carbides, such as D2 or a PM tool steel. For galling, the solution is often a low-friction PVD coating like WC/C or CrN, combined with proper lubrication. Surface treatments like nitriding also significantly improve wear resistance.

Plastic Deformation (Sinking)

Problem: This failure occurs when the stress from the forming operation exceeds the die material's compressive yield strength, causing the die to permanently deform, or "sink." This is especially common in hot-work applications where high temperatures soften the tool steel. The result is parts that are out of dimensional tolerance.

Solution: The mitigation strategy is to choose a material with higher compressive strength at the operating temperature. For cold work, this may mean upgrading to a harder tool steel. For hot work, selecting a superior hot-work grade like H13 or a specialty alloy is necessary. Ensuring proper heat treatment to maximize hardness is also critical.

Chipping

Problem: Chipping is a fatigue-based failure where small pieces break away from the sharp edges or corners of a die. It happens when localized stresses exceed the material's fatigue strength. This is often a sign that the die material is too brittle (lacks toughness) for the application, a common issue when using very hard tool steels for high-impact operations.

Solution: The primary solution is to select a tougher material. This might involve switching from a wear-resistant grade like D2 to a shock-resistant grade like S7, or upgrading to a PM tool steel that offers a better balance of toughness and wear resistance. Proper tempering after hardening is also essential to relieve internal stresses and maximize toughness.

Cracking (Brittle Fracture)

Problem: This is the most severe failure mode, involving a large, often catastrophic crack that renders the die useless. Cracks typically initiate from stress concentrators like sharp corners, machining marks, or internal metallurgical defects. They propagate rapidly when the operating stress exceeds the material's fracture toughness.

Solution: Preventing brittle fracture requires a focus on both material selection and design. Use a material with high toughness and cleanliness (few internal defects), such as an ESR or PM grade. In the design phase, incorporate generous radii on all internal corners to reduce stress concentration. Finally, proactive diagnostics like Liquid Penetrant Testing during maintenance can detect surface-breaking micro-cracks before they lead to catastrophic failure.

Optimizing Die Performance for the Long Term

Achieving superior performance in automotive forming is not a one-time decision but a continuous process of strategic selection, system integration, and proactive management. The key takeaway is to move beyond the simplistic metrics of initial cost and hardness. Instead, a successful approach is grounded in the Total Cost of Ownership, where a higher upfront investment in premium materials, coatings, and heat treatments is justified by substantially longer die life, reduced downtime, and higher quality parts.

The most durable and efficient solutions arise from treating the die as an integrated system—a performance trinity where a tough substrate, precise heat treatment, and a tailored surface coating work in harmony. By diagnosing potential failure modes before they occur and selecting a combination of materials and processes to counter them, manufacturers can transform tooling from a consumable expense into a reliable, high-performance asset. This strategic mindset is the foundation for building a more efficient, profitable, and competitive manufacturing operation.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the best material for die making?

There is no single "best" material; the optimal choice is application-dependent. For high-volume cold-work applications requiring excellent wear resistance, high-carbon, high-chromium tool steels like D2 (or its equivalents like 1.2379) are a classic choice. However, when forming advanced high-strength steels (AHSS), tougher materials like shock-resistant steels (e.g., S7) or advanced Powder Metallurgy (PM) steels are often superior to prevent chipping and cracking.

2. What is the most suitable material for die casting?

For die casting dies that handle molten metals like aluminum or zinc, hot-work tool steels are the standard. H13 (1.2344) is the most widely used grade due to its excellent combination of hot strength, toughness, and resistance to thermal fatigue (heat checking). For more demanding applications, premium H13 variants or other specialized hot-work grades may be used.

3. What material properties are important for bending forming?

For bending operations, key material properties include high yield strength to resist deformation, good wear resistance to maintain the die's profile over time, and sufficient toughness to prevent chipping at sharp radii. The material's ductility and plasticity are also important considerations as they influence how the workpiece material flows and forms without fracturing.

4. What is the best steel for forging dies?

Forging dies are subjected to extreme impact loads and high temperatures, requiring materials with exceptional hot strength and toughness. Hot-work tool steels are the primary choice. Grades like H11 and H13 are very common for conventional forging dies, as they are designed to withstand the intense thermal and mechanical stresses of the process without softening or fracturing.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —