Hot Stamping vs Cold Stamping Automotive Parts: The Engineering Decision Guide

TL;DR

The choice between hot stamping and cold stamping for automotive parts fundamentally depends on the balance between tensile strength, geometric complexity, and production cost. Hot stamping (press hardening) is the industry standard for safety-critical "Body-in-White" components like A-pillars and door rings, heating boron steel to 950°C to achieve ultra-high strengths (1,500+ MPa) with zero springback, albeit at higher cycle times (8–20 seconds). Cold stamping remains the efficiency leader for high-volume chassis and structural parts, offering lower energy costs and rapid production speeds, though it faces challenges with springback when forming modern 1,180 MPa Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS).

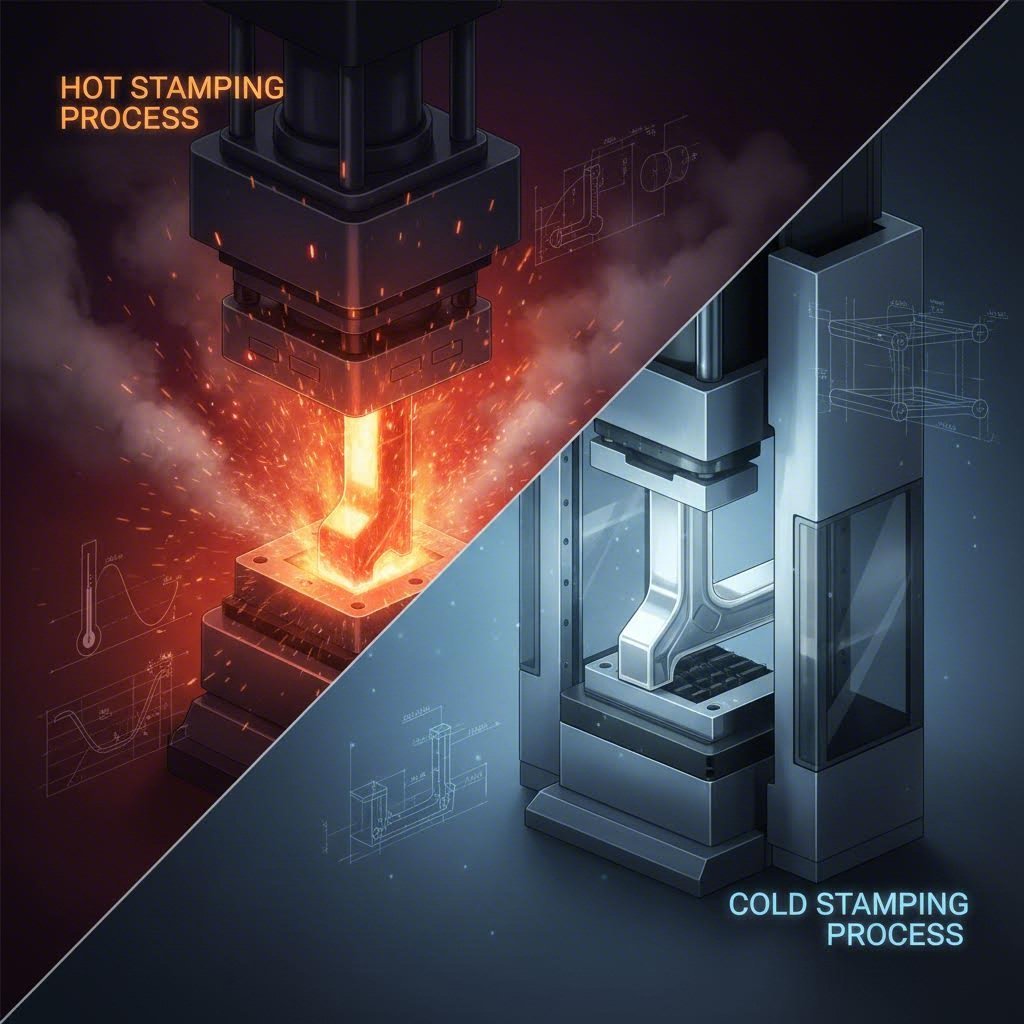

The Core Mechanism: Heat vs. Pressure

At an engineering level, the dividing line between these two processes is the recrystallization temperature of the metal. This thermal threshold dictates whether the microstructure of the steel changes during deformation or merely hardens through mechanical stress.

Hot stamping, also known as press hardening, involves heating the blank above its austenitization temperature (typically 900–950°C) before forming. The key is that the forming and quenching happen simultaneously within the water-cooled die. This rapid cooling transforms the steel’s microstructure from ferrite-pearlite into martensite, the hardest phase of steel. The result is a component that enters the press soft and pliable but exits as an ultra-high-strength safety shield.

Cold stamping occurs at room temperature (well below the recrystallization point). It relies on work hardening (or strain hardening), where the plastic deformation itself dislocates the crystal lattice to increase strength. While modern cold stamping presses—especially servo and transfer systems—can exert massive tonnage (up to 3,000 tons), the material’s formability is limited by its initial ductility. Unlike hot stamping, which "resets" the material state with heat, cold stamping must fight against the metal's natural tendency to return to its original shape, a phenomenon known as springback.

Hot Stamping (Press Hardening): The Safety Cage Solution

Hot stamping has become synonymous with the automotive "safety cage." As emissions regulations drive lightweighting and crash safety standards tighten, OEMs have turned to press hardening to produce thinner, stronger parts that don't compromise occupant protection.

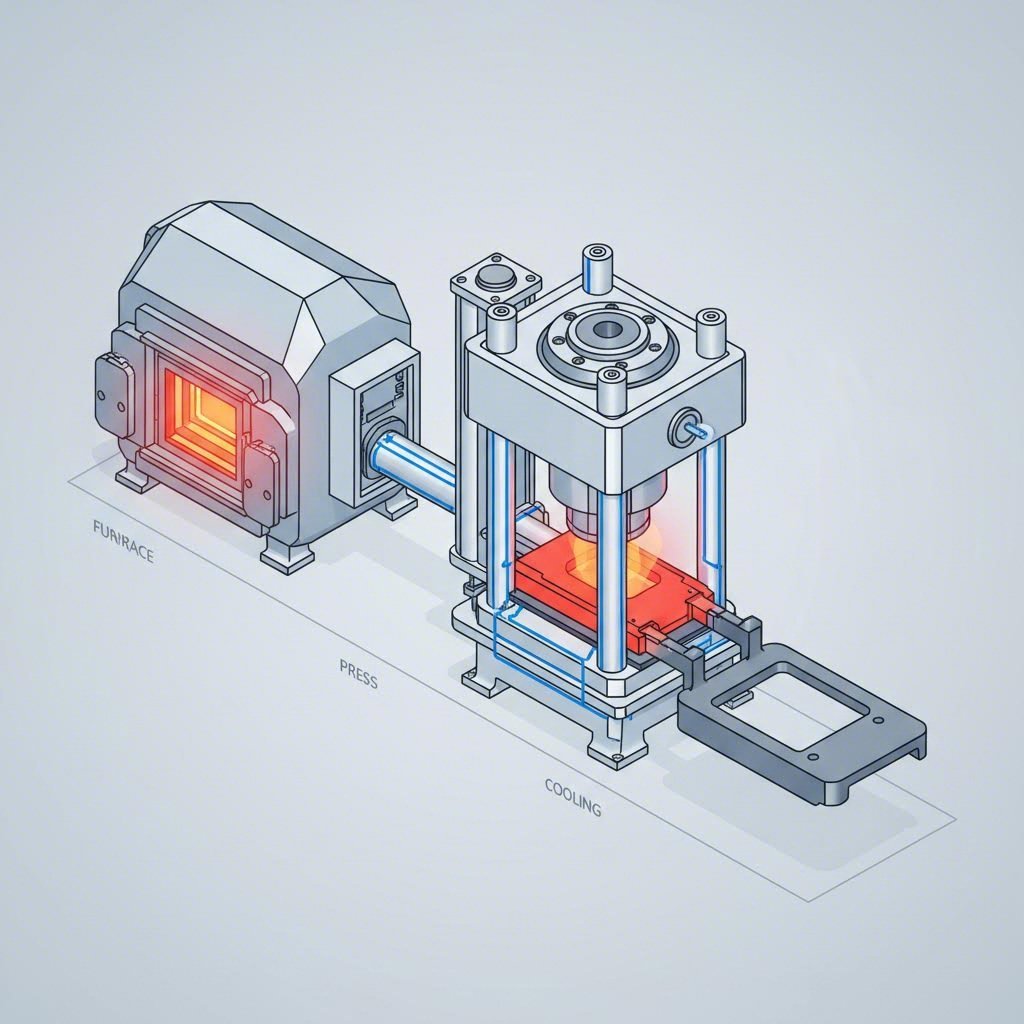

The Process: Austenitization and Quenching

The standard material for this process is 22MnB5 boron steel. The process flow is distinct and energy-intensive:

- Heating: Blanks travel through a roller-hearth furnace (often 30+ meters long) to reach ~950°C.

- Transfer: Robots rapidly move the glowing blanks to the press (transfer time <3 seconds to prevent premature cooling).

- Forming & Quenching: The die closes, forming the part while simultaneously cooling it at a rate of >27°C/s. This "holding time" in the die (5–10 seconds) is the bottleneck for cycle time.

The "Zero Springback" Advantage

The defining advantage of hot stamping is dimensional accuracy. Because the part is formed while hot and ductile, and then "frozen" into shape during the martensitic transformation, there is virtually no springback. This allows for complex geometries, such as one-piece door rings or intricate B-pillars, which would be impossible to stamp cold without severe warping or cracking.

Typical Applications

- A-Pillars and B-Pillars: Critical for rollover protection.

- Roof Rails and Door Rings: Integrating multiple parts into single high-strength components.

- Bumpers and Impact Beams: Requiring yield strengths often exceeding 1,200 MPa.

Cold Stamping: The Efficiency Workhorse

While hot stamping wins on ultimate strength and complexity, cold stamping dominates in volume efficiency and operational cost. For components that do not require complex, deep-draw geometries at gigapascal strength levels, cold stamping is the superior economic choice.

The Rise of 3rd Gen AHSS

Historically, cold stamping was limited to softer steels. However, the advent of 3rd Generation Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS), such as Quench and Partition (QP980) or TRIP-aided Bainitic Ferrite (TBF1180), has closed the gap. These materials allow cold stamped parts to reach tensile strengths of 1,180 MPa or even 1,500 MPa, encroaching on territory previously reserved for hot stamping.

Speed and Infrastructure

A cold stamping line, typically using progressive or transfer dies, operates continuously. Unlike the stop-and-go nature of press hardening (waiting for the quench), cold stamping presses can run at high stroke rates, producing parts in a fraction of a second. There is no furnace to power, significantly reducing the energy footprint per part.

For manufacturers seeking to leverage this efficiency for high-volume components, partnering with a capable supplier is critical. Companies like Shaoyi Metal Technology bridge the gap between prototyping and mass production, offering IATF 16949-certified precision stamping with press capacities up to 600 tons. Their ability to handle complex subframes and control arms demonstrates how modern cold stamping can meet rigorous OEM standards.

The Springback Challenge

The primary engineering hurdle in cold stamping high-strength steel is springback. As yield strength increases, the elastic recovery after forming increases. Tooling engineers must use sophisticated simulation software to design "compensated" dies that over-bend the metal, anticipating it will snap back to the correct tolerance. This makes tool design for cold AHSS significantly more expensive and iterative than for hot stamping.

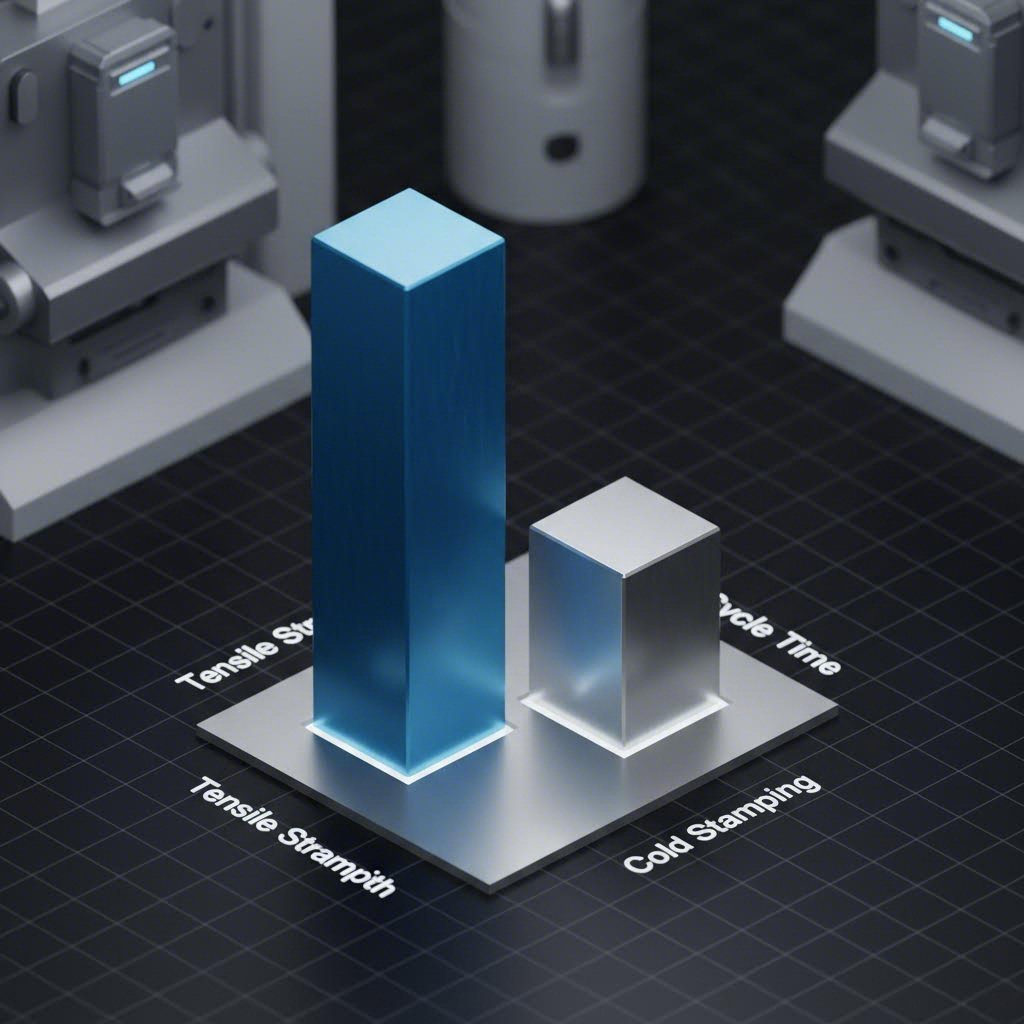

Critical Comparison Matrix

For procurement officers and engineers, the decision often comes down to a direct trade-off between performance metrics and production economics. The table below outlines the general consensus for automotive applications.

| Feature | Hot Stamping (Press Hardening) | Cold Stamping (AHSS) |

|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength | 1,300 – 2,000 MPa (Ultra High) | 300 – 1,200 MPa (Typical) |

| Cycle Time | 8 – 20 seconds (Slow) | < 1 second (Fast) |

| Springback | Minimal / Near Zero | Significant (Requires Compensation) |

| Geometric Complexity | High (Intricate shapes possible) | Low to Medium |

| Tooling Cost | High (Cooling channels, specialty steel) | Medium (Higher for AHSS compensation) |

| Capital Investment | Very High (Furnace + Laser Trimming) | Medium (Press + Coil Line) |

| Energy Consumption | High (Furnace heating) | Low (Mechanical force only) |

Technological Convergence: The Gap is Closing

The binary distinction between "hot" and "cold" is becoming less rigid. The industry is seeing a convergence where new technologies attempt to mitigate the downsides of each process.

- Press Quenched Steels (PQS): These are hybrid materials designed for hot stamping but engineered to retain some ductility (unlike fully brittle martensite). This allows for "tailored properties" within a single part—rigid in the impact zone, but ductile in the crush zone to absorb energy.

- Cold Formable 1500 MPa: Steelmakers are introducing cold-formable martensitic grades (MS1500) that can achieve hot-stamped strength levels without the furnace. However, these are currently limited to simple shapes like roll-formed rocker panels or bumper beams due to extremely limited formability.

Ultimately, the decision matrix prioritizes geometry. If the part has a complex shape (deep draw, tight radii) and requires >1,000 MPa strength, hot stamping is often the only viable option. If the geometry is simpler or the strength requirement is <1,000 MPa, cold stamping offers a significant cost and speed advantage.

Conclusion: Choosing the Right Process

The "hot vs. cold" debate is not about one process being superior, but about matching the manufacturing method to the component's function in the vehicle architecture. Hot stamping remains the undisputed king of the safety cage—essential for protecting passengers with high-strength, complex structural pillars. It is the premium solution where failure is not an option.

Conversely, cold stamping is the backbone of automotive mass production. Its evolution with 3rd Gen AHSS materials allows it to handle an increasing load of structural duties, delivering lightweighting benefits without the cycle-time penalty of press hardening. For procurement teams, the strategy is clear: specify hot stamping for complex, intrusion-resistant safety parts, and maximize cold stamping for everything else to keep program costs competitive.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the difference between hot and cold stamping?

The primary difference lies in temperature and material transformation. Hot stamping heats the metal to ~950°C to alter its microstructure (creating martensite), enabling the formation of complex, ultra-high-strength parts with no springback. Cold stamping shapes metal at room temperature using high pressure, relying on work hardening. It is faster and more energy-efficient but limited by springback and lower formability in high-strength grades.

2. Why is hot stamping used for automotive A-pillars?

A-pillars require a unique combination of complex geometry (to match the vehicle design and visibility lines) and extreme strength (to prevent roof collapse in a rollover). Hot stamping allows 22MnB5 steel to be formed into these intricate shapes while achieving tensile strengths of 1,500+ MPa, a combination that cold stamping generally cannot achieve without cracking or severe warping.

3. Does cold stamping produce weaker parts than hot stamping?

Generally, yes, but the gap is closing. Traditional cold stamping usually caps out around 590–980 MPa for complex parts. However, modern 3rd Generation AHSS (Advanced High-Strength Steels) allow cold stamped parts to reach 1,180 MPa or even 1,470 MPa in simpler shapes. Still, for the highest tier of strength (1,800–2,000 MPa), hot stamping is the only commercial solution.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —