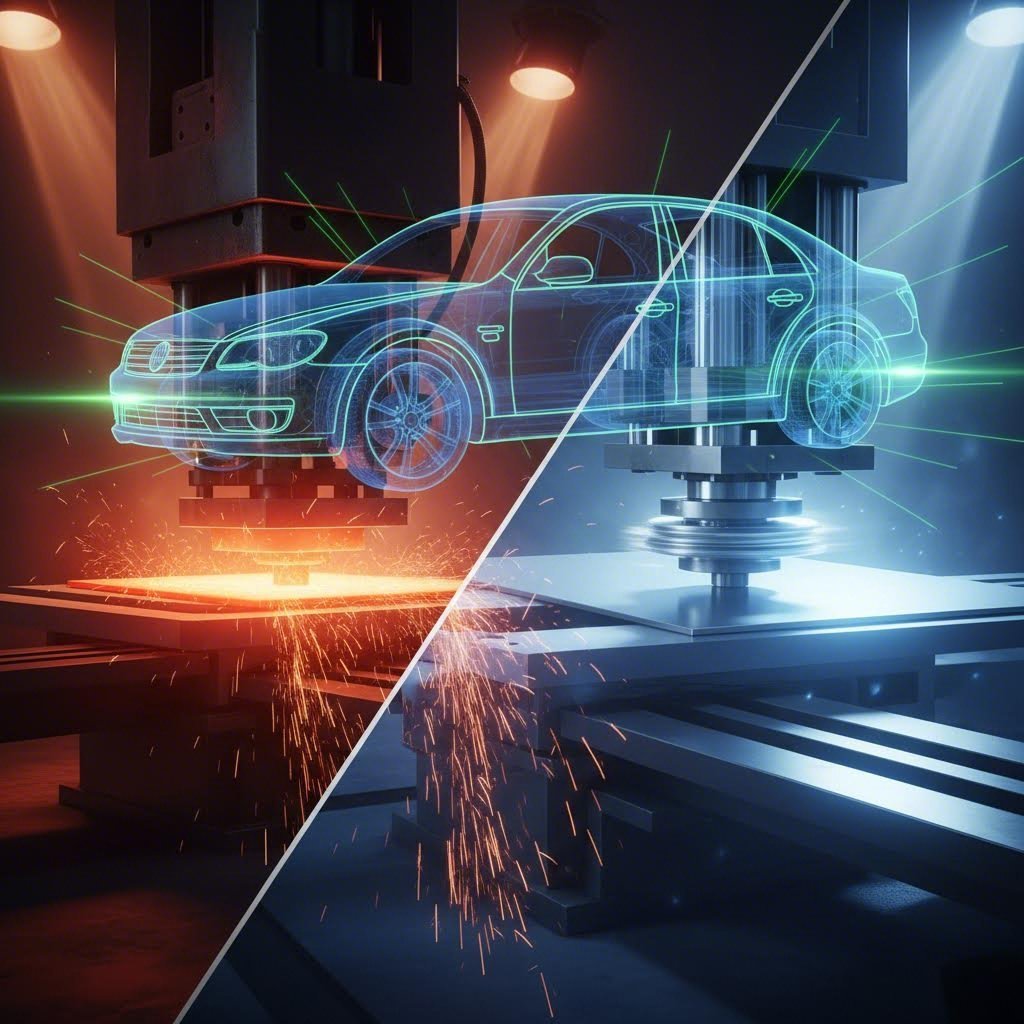

Hot Stamping vs Cold Stamping Automotive: Critical Engineering Trade-offs

TL;DR

Hot stamping (press hardening) is the industry standard for safety-critical automotive components like B-pillars and roof rails. It heats boron steel to ~950°C to achieve ultra-high tensile strengths (1500+ MPa) with complex geometries and virtually zero springback, though at a higher cost per part. Cold stamping remains the dominant method for high-volume structural parts and body panels, offering superior speed, energy efficiency, and lower costs for steels up to 1180 MPa. The choice depends on balancing the need for crashworthiness against production volume and budget constraints.

The Core Difference: Temperature & Microstructure

The fundamental distinction between hot stamping and cold stamping lies in the manipulation of the metal's phase transformations versus its work-hardening properties. This is not merely a difference in processing temperature; it is a divergence in how strength is engineered into the final component.

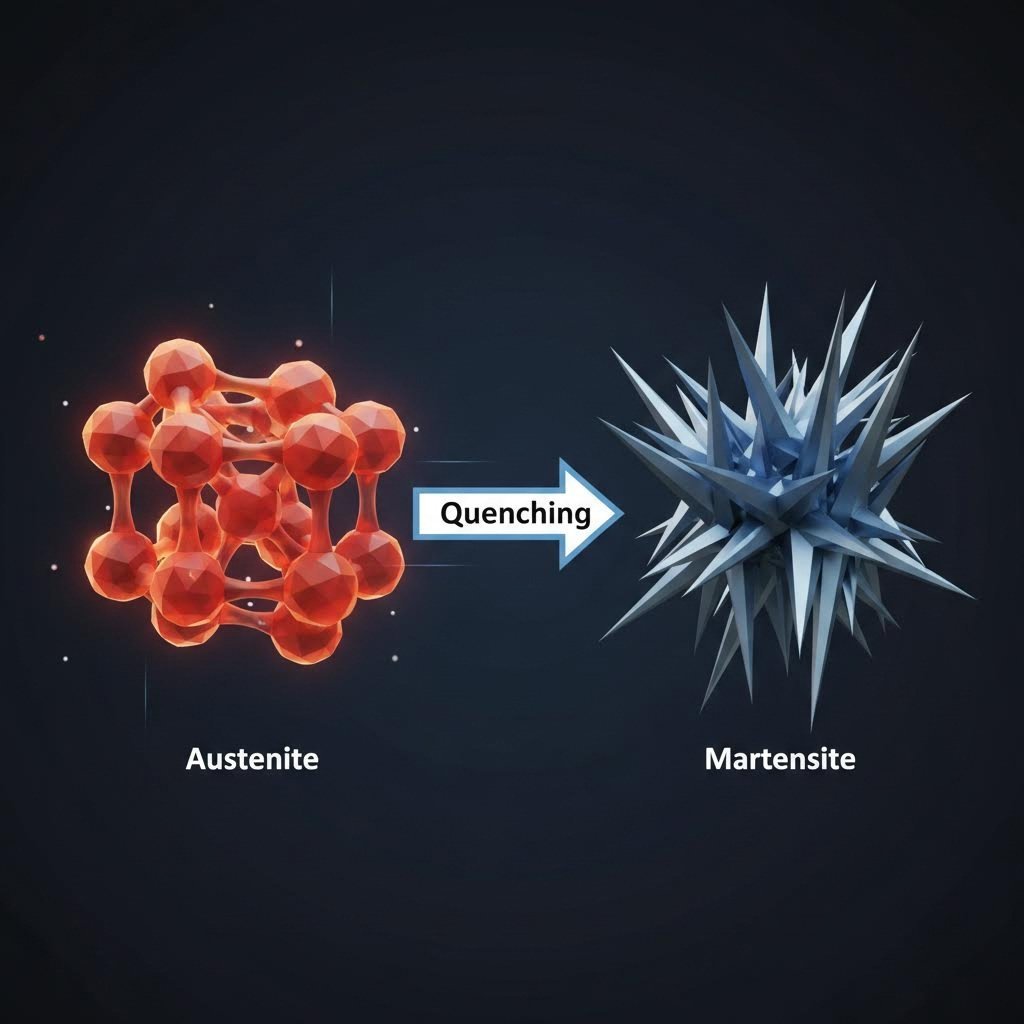

Hot stamping relies on a phase transformation. Low-alloy boron steel (typically 22MnB5) is heated to approximately 900°C–950°C until it creates a homogeneous austenitic microstructure. It is then formed and rapidly quenched (cooled) within the die. This quenching transforms the austenite into martensite, a distinct crystalline structure that provides exceptional hardness and tensile strength.

Cold stamping, conversely, operates at ambient temperature. It creates strength through work hardening (plastic deformation) and the inherent properties of the raw material, such as Advanced High-Strength Steel (AHSS) or Ultra-High-Strength Steel (UHSS). There is no phase change during the forming process; instead, the material's grain structure is elongated and strained to resist further deformation.

| Feature | Hot Stamping (Press Hardening) | Cold Stamping |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | ~900°C – 950°C (Austenitization) | Ambient (Room Temperature) |

| Primary Material | Boron Steel (e.g., 22MnB5) | AHSS, UHSS, Aluminum, HSS |

| Strengthening Mechanism | Phase Transformation (Austenite to Martensite) | Work Hardening & Initial Material Grade |

| Max Tensile Strength | 1500 – 2000 MPa | Typically ≤1180 MPa (some up to 1470 MPa) |

| Springback | Virtually Zero (High Geometric Accuracy) | Significant (Requires Compensation) |

Hot Stamping: The Safety Specialist

Hot stamping, often called press hardening, has revolutionized automotive safety cells. By enabling the production of components with tensile strengths exceeding 1500 MPa, engineers can design thinner, lighter parts that maintain or improve crash performance. This "lightweighting" capability is critical for modern fuel efficiency standards and EV range optimization.

The process is ideal for complex shapes that would crack under cold forming. Because the steel is hot and malleable during the stroke, it can be formed into intricate geometries with deep draws in a single step. Once the die closes and quenches the part, the resulting component is dimensionally stable with almost no springback. This precision is vital for assembly, as it reduces the need for downstream corrections.

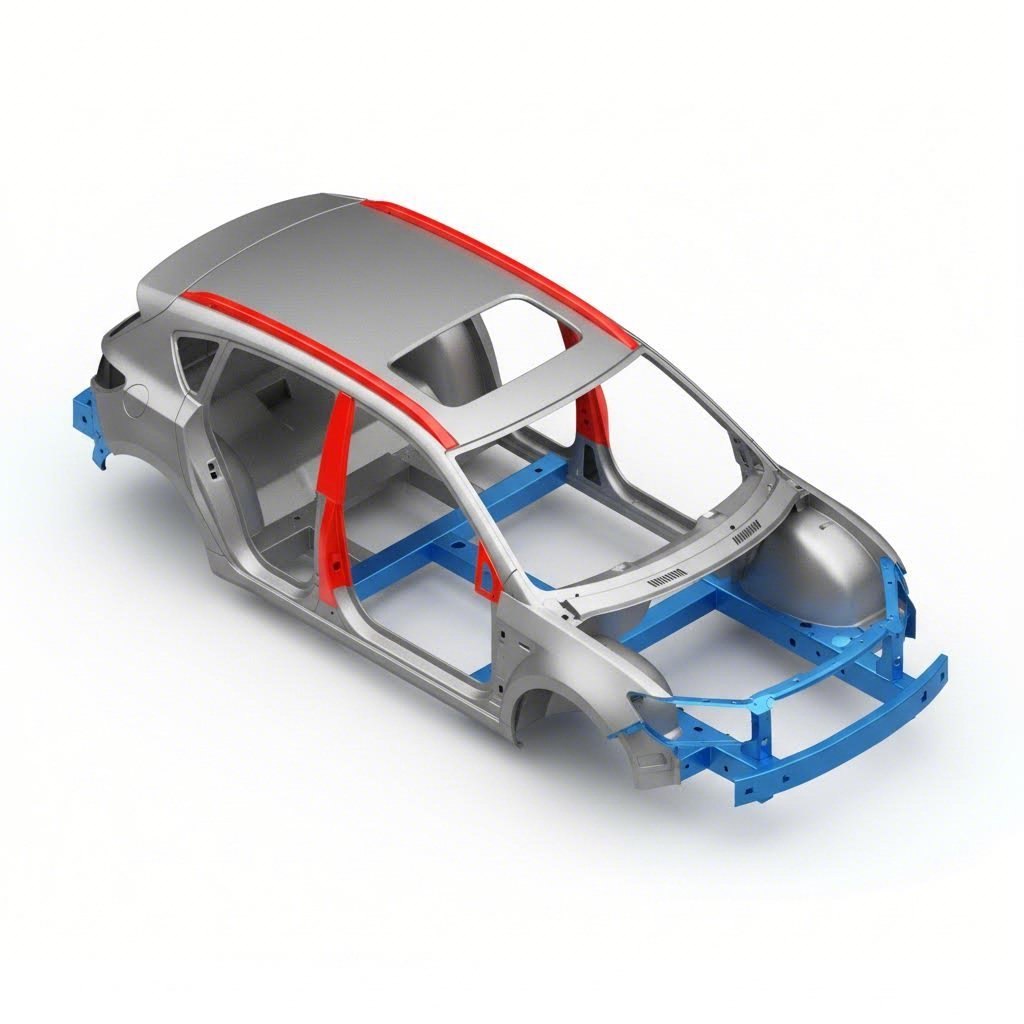

A unique advantage of hot stamping is the ability to create "soft zones" or tailored properties within a single part. By controlling the cooling rate in specific areas of the die, engineers can leave certain sections ductile (to absorb energy) while others are fully hardened (to resist intrusion). This is frequently applied in B-pillars, where the upper section must be rigid to protect occupants during a rollover, while the lower section crumples to manage impact energy.

Key Applications

- A-Pillars and B-Pillars: Critical anti-intrusion zones.

- Roof Rails and Bumpers: High strength-to-weight ratio requirements.

- EV Battery Enclosures: Protection against side impacts to prevent thermal runaway.

- Door Beams: Intrusion resistance.

Cold Stamping: The Mass Production Workhorse

Despite the rise of hot forming, cold stamping remains the backbone of automotive manufacturing due to its unmatched speed and cost-efficiency. For components that do not require the extreme 1500+ MPa strength of martensitic steel, cold stamping is almost always the more economical choice. Modern presses can run at high stroke rates (often 40+ strokes per minute), significantly outpacing the cycle times of hot stamping lines which are limited by heating and cooling durations.

Recent advancements in metallurgy have expanded the capabilities of cold stamping. Third-generation (Gen 3) steels and modern martensitic grades allow cold forming of parts with tensile strengths up to 1180 MPa and, in specialized cases, 1470 MPa. This allows manufacturers to achieve significant strength without the capital investment of furnaces and laser trimming cells required for hot stamping.

However, cold stamping high-strength materials introduces the challenge of springback—the tendency of metal to return to its original shape after forming. Managing springback in UHSS requires sophisticated simulation software and complex die engineering. Manufacturers must often compensate for "wall curling" and angular changes, which can increase tooling development time.

For manufacturers seeking a partner capable of navigating these complexities, Shaoyi Metal Technology offers comprehensive cold stamping solutions. With press capabilities up to 600 tons and IATF 16949 certification, they bridge the gap from rapid prototyping to high-volume production for critical components like control arms and subframes, ensuring global OEM standards are met.

Key Applications

- Chassis Components: Control arms, crossmembers, and subframes.

- Body Panels: Fenders, hoods, and door skins (often aluminum or mild steel).

- Structural Brackets: High-volume reinforcements and mountings.

- Seating Mechanisms: Rails and recliners requiring tight tolerances.

Critical Comparison: Engineering Trade-offs

Selecting between hot and cold stamping is rarely a matter of preference; it is a calculation of trade-offs involving cost, cycle time, and design constraints.

1. Cost Implications

Hot stamping is inherently more expensive per part. The energy cost to heat furnaces to 950°C is substantial, and the cycle involves a dwell time for quenching, reducing throughput. Additionally, boron steel parts typically require laser trimming after hardening because mechanical shears wear out instantly against martensitic steel. Cold stamping avoids these energy costs and secondary laser processes, making it cheaper for high-volume runs.

2. Complexity vs. Accuracy

Hot stamping offers superior dimensional accuracy ("what you design is what you get") because the phase transformation locks the geometry in place, eliminating springback. Cold stamping involves a constant battle against elastic recovery. For simple geometries, cold stamping is precise; for complex, deep-draw parts in high-strength steel, hot stamping provides better geometric fidelity.

3. Welding and Assembly

Joining these materials requires different strategies. Hot-stamped parts often use an Aluminum-Silicon (Al-Si) coating to prevent oxidation in the furnace. However, this coating can contaminate welds if not properly managed, potentially leading to issues like segregation or weaker joints. Zinc-coated steels used in cold stamping are easier to weld but carry risks of Liquid Metal Embrittlement (LME) if subjected to specific thermal cycles during assembly.

Automotive Application Guide: Which to Choose?

To finalize the decision, engineers should map the component's requirements against the process capabilities. Use this decision matrix to guide the selection:

-

Choose Hot Stamping If:

The part is part of the safety cage (B-pillar, rocker reinforcement) requiring >1500 MPa strength. The geometry is complex with deep draws that would split in cold forming. You need "zero springback" for assembly fit-up. Lightweighting is the primary KPI, justifying the higher piece price. -

Choose Cold Stamping If:

The part requires strength <1200 MPa (e.g., chassis parts, crossmembers). Production volumes are high (>100,000 units/year) where cycle time is critical. The geometry allows for progressive die forming. Budget constraints prioritize lower piece cost and tooling investment.

Ultimately, a modern vehicle architecture is a hybrid design. It utilizes hot stamping for the passenger safety cell to ensure survival in crashes and cold stamping for energy-absorbing zones and structural framework to maintain cost-effectiveness and reparability.

FAQ

1. What is the difference between hot and cold stamping?

The primary difference is the temperature and strengthening mechanism. Hot stamping heats boron steel to ~950°C to transform its microstructure into ultra-hard martensite (1500+ MPa) upon quenching. Cold stamping forms metal at room temperature, relying on the material's initial properties and work hardening, typically achieving strengths up to 1180 MPa with lower energy costs.

2. What are the disadvantages of hot stamping?

Hot stamping has higher operational costs due to the energy required for furnaces and the slower cycle times (due to heating and cooling). It also typically requires expensive laser trimming for post-process cutting, as the hardened steel damages traditional mechanical shears. Additionally, the Al-Si coatings used can complicate welding processes compared to standard zinc-coated steels.

3. Can cold stamping achieve the same strength as hot stamping?

Generally, no. While cold stamping technologies have advanced with Gen 3 steels reaching 1180 MPa or even 1470 MPa in limited geometries, they cannot reliably match the 1500–2000 MPa tensile strength of hot-stamped martensitic steel. Furthermore, forming ultra-high-strength steel cold leads to significant springback and formability challenges that hot stamping avoids.

4. Why is springback a problem in cold stamping?

Springback occurs when the metal tries to return to its original shape after the forming force is removed, caused by elastic recovery. In high-strength steels, this effect is more pronounced, leading to "wall curling" and dimensional inaccuracies. Hot stamping eliminates this by locking the shape in during the phase transformation from austenite to martensite.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —