Forged Aluminum Grades For Cars: Match The Right Alloy To Every Part

Why Forged Aluminum Grades Matter for Automotive Performance

When you think about what makes a modern aluminum car perform at its best, the answer often lies beneath the surface—in the very structure of the metal itself. Forged aluminum has become essential in automotive manufacturing, powering everything from suspension components to high-performance wheels. But here's the critical question most engineers and procurement professionals face: with so many aluminum grades available, how do you match the right alloy to every part?

Understanding this connection between alloy selection and component performance can mean the difference between a vehicle that excels and one that merely meets minimum standards. So, what is aluminum alloy exactly, and why does the forming method matter so much?

Why Forging Transforms Aluminum Performance

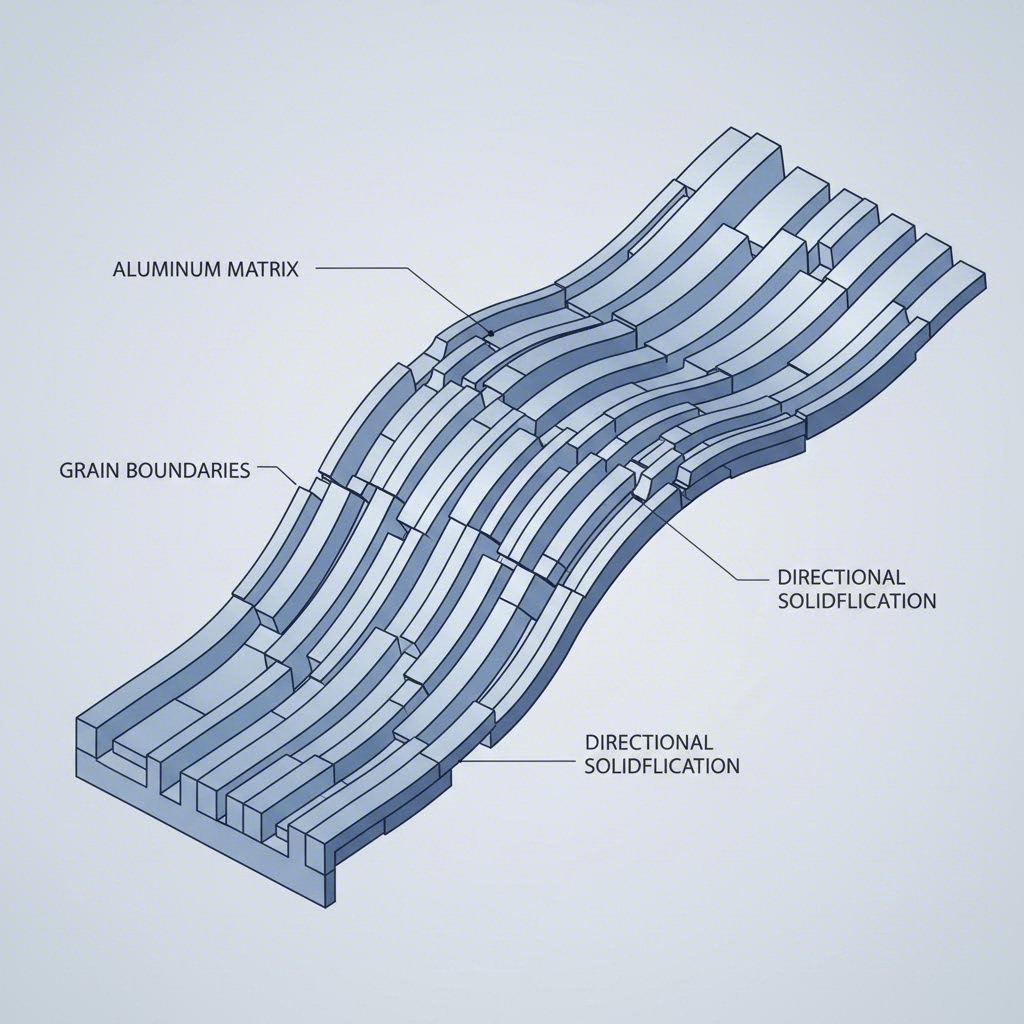

Unlike casting—where molten aluminum is poured into molds—or extrusion, which pushes heated metal through a die, forging applies intense pressure to shape aluminum at elevated temperatures. This process fundamentally changes the material's internal structure. The result? A denser, more continuous grain flow that follows the contours of the finished part.

According to manufacturing experts, forging compresses aluminum's grain structure, significantly enhancing both strength and toughness compared to cast alternatives. This refined microstructure also improves fatigue resistance and impact performance—properties that are non-negotiable for safety-critical automotive aluminum applications.

Forging refines aluminum's grain structure by compressing and aligning internal fibers, delivering mechanical properties that cast alternatives simply cannot match—especially for components subjected to repeated stress cycles.

This is why an alum car built with forged components in critical areas demonstrates superior durability under real-world driving conditions. The forging process eliminates internal voids and porosity common in castings, ensuring each aluminum automobile component can withstand the demanding loads of modern vehicles.

The Grade Selection Challenge in Automotive Manufacturing

Here's where it gets interesting—and complex. Not all aluminum grades forge equally well, and not every forged grade suits every application. Selecting the wrong alloy can lead to manufacturing difficulties, premature part failure, or unnecessary costs.

Engineers must balance several competing factors when choosing aluminum grades for automotive components:

- Strength requirements: Does the part need maximum tensile strength or good formability?

- Operating environment: Will the component face corrosive conditions or extreme temperatures?

- Manufacturing constraints: How complex is the part geometry, and what forging temperatures are feasible?

- Cost considerations: Does the application justify premium alloys, or will standard grades suffice?

This article serves as your practical selection guide, walking you through the essential forged aluminum grades used in today's vehicles. You'll discover which alloys suit specific component categories, understand the critical role of heat treatment, and learn how to avoid common selection mistakes. Whether you're specifying materials for suspension arms, wheels, or powertrain parts, matching the right grade to every application ensures both performance and value.

Aluminum Alloy Series and Their Forging Suitability

Before you can match the right alloy to an automotive component, you need to understand how aluminum alloys are organized. The Aluminum Association established a numbering system that categorizes wrought aluminum alloys into series based on their primary alloying element. This classification—ranging from 1xxx through 7xxx—tells you a great deal about an alloy's behavior during forging and its final performance characteristics.

But here's what many material specifications don't explain: why do certain aluminium alloy grades forge beautifully while others crack, distort, or simply refuse to cooperate? The answer lies in metallurgy, and understanding these fundamentals will transform how you approach grade selection for automotive applications.

Understanding the Aluminum Series System

Each aluminum alloy series is defined by its dominant alloying element, which determines the alloy's core properties. Think of it as a family tree where relatives share certain traits:

- 1xxx Series: Essentially pure aluminum (99%+ Al). Excellent corrosion resistance and conductivity, but too soft for structural automotive forgings.

- 2xxx Series: Copper is the primary additive. These alloys deliver high strength and excellent fatigue resistance—ideal for demanding aerospace and automotive powertrain applications.

- 3xxx Series: Manganese-alloyed. Moderate strength with good formability, but rarely used in forging because they cannot be heat-treated to higher strengths.

- 4xxx Series: Silicon-dominant. The high silicon content provides excellent wear resistance, making these alloys suitable for pistons, though they present machining challenges.

- 5xxx Series: Magnesium-based. Outstanding corrosion resistance and weldability, commonly forged for marine and cryogenic applications rather than typical automotive parts.

- 6xxx Series: Magnesium and silicon combined. This balanced chemistry delivers the versatility that makes 6xxx alloys the workhorses of automotive aluminum forging.

- 7xxx Series: Zinc, along with magnesium and copper, creates ultra-high-strength alloys. These represent the strongest aluminum alloys available, essential for weight-critical aerospace and high-performance automotive structures.

According to industry documentation from the Aluminum Association, this naming convention emerged after WWII to bring discipline to the growing catalog of aluminum materials. Understanding al alloy grades within this framework helps you quickly narrow down candidates for any given application.

Forgeability Factors Across Alloy Families

Here's where the real engineering insight comes in. Not every aluminum alloy forges the same way, and the differences aren't arbitrary—they're rooted in how each alloy's chemistry affects its behavior under pressure and heat.

Forgeability depends on several interconnected factors:

- Deformation resistance: How much force does the alloy require to flow into die cavities?

- Temperature sensitivity: How dramatically do properties change across the forging temperature range?

- Cracking tendency: Does the alloy tolerate severe deformation without developing surface or internal defects?

- Heat treatability: Can the forged part be strengthened through subsequent thermal processing?

Research from ASM International demonstrates that forgeability improves with increasing metal temperature for all aluminum alloys—but the magnitude of this effect varies considerably. High-silicon 4xxx alloys show the greatest temperature sensitivity, while high-strength 7xxx alloys display the narrowest workable temperature window. This explains why 7xxx series alloys demand precise temperature control: there's less margin for error.

The 6xxx series, particularly alloys like 6061, earns its reputation as "highly forgeable" because it offers a favorable combination of moderate flow stress and forgiving process windows. In contrast, 2xxx and 7xxx alloys exhibit higher flow stresses—sometimes exceeding those of carbon steel at typical forging temperatures—making them more challenging but necessary for high-performance components.

| Alloy Series | Primary Alloying Element | Forgeability Rating | Typical Automotive Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2xxx | Copper | Moderate | Pistons, connecting rods, engine components | High-temperature strength, superior fatigue resistance, heat-treatable |

| 5xxx | Magnesium | Good | Structural components in corrosive environments, marine-grade parts | Non-heat-treatable, exceptional marine corrosion resistance, high as-welded strength |

| 6xxx | Magnesium + Silicon | Excellent | Suspension arms, control arms, wheels, general structural parts | Balanced strength and formability, good corrosion resistance, heat-treatable, cost-effective |

| 7xxx | Zinc (+ Mg, Cu) | Moderate to Difficult | High-stress chassis components, performance wheels, aerospace-grade automotive parts | Ultra-high strength, excellent fatigue resistance, requires careful process control, heat-treatable |

Why does chemistry matter so much for forging versus other forming methods? When aluminum is cast, the metal solidifies from a liquid state, often trapping porosity and developing coarse grain structures. Extrusion pushes heated metal through fixed die openings, limiting geometric complexity. Forging, however, compresses the metal under tremendous pressure, refining the grain structure and eliminating internal voids—but only if the alloy can tolerate this severe deformation without cracking.

The common aluminum alloys used in automotive forging—primarily from the 2xxx, 6xxx, and 7xxx families—share a critical trait: they're all heat-treatable. This means their strength can be significantly enhanced after forging through solution treatment and aging processes. Non-heat-treatable alloys like the 5xxx series find limited use in automotive forgings because they cannot achieve the strength levels demanded by most vehicle components.

With this foundation in aluminum alloy grades and their forging behavior, you're ready to explore the specific grades that dominate automotive manufacturing—and understand exactly why engineers choose each one for particular applications.

Essential Forged Aluminum Grades for Automotive Components

Now that you understand how aluminum alloy families differ in their forging behavior, let's examine the specific grades that dominate automotive manufacturing. These five alloys—6061, 6082, 7075, 2024, and 2014—represent the core material options you'll encounter when specifying forged components. Each brings distinct advantages, and understanding their differences helps you make informed decisions that balance performance, cost, and manufacturability.

What makes these particular aluminum material grades so prevalent in vehicles? The answer lies in their optimized balance of strength, formability, and application-specific properties that have been refined through decades of automotive engineering experience.

6061 and 6082 for Structural Components

The 6xxx series dominates automotive forging for good reason. These magnesium-silicon alloys deliver the versatility that engineers need across a wide range of structural applications—without the premium pricing or manufacturing challenges of higher-strength alternatives.

6061 Aluminum stands as the most commonly used aluminum alloy in general manufacturing, and automotive applications are no exception. According to Protolabs' alloy comparison data, 6061 is "generally selected where welding or brazing is required or for its high corrosion resistance in all tempers." This makes it ideal for automotive parts, pipelines, furniture, consumer electronics, and structural components that may require joining during assembly.

Key characteristics of 6061 include:

- Composition: Primary alloying elements are magnesium (0.8-1.2%) and silicon (0.4-0.8%), with small additions of copper and chromium

- Weldability: Excellent—though welding can weaken the heat-affected zone, requiring post-weld treatment for strength recovery

- Corrosion resistance: Very good in all temper conditions

- Typical automotive uses: Structural frames, brackets, general CNC-machined parts, components requiring subsequent welding

6082 Aluminum represents a significant development in European automotive forging that many North American specifications overlook. This alloy has become almost exclusively used for automotive suspension and chassis components in European vehicle programs—and for compelling metallurgical reasons.

According to the European Aluminium Association's technical documentation, "Due to its excellent corrosion resistance alloy EN AW-6082-T6 is almost exclusively used for automotive suspension and chassis components." The documentation shows that major European manufacturers use 6082-T6 for control arms, steering knuckles, couplings, clutch cylinders, and drive shaft components.

What makes 6082 particularly suited for aluminum for automotive applications?

- Composition: Higher silicon (0.7-1.3%) and manganese (0.4-1.0%) content compared to 6061, along with magnesium (0.6-1.2%)

- Strength advantage: Slightly higher strength than 6061 in the T6 temper, with better performance under cyclic loading

- Corrosion performance: The general corrosion resistance is regarded as very good, with blast cleaning using aluminum shot providing additional surface protection

- Fatigue behavior: Forged 6082-T6 components endure approximately twice the strain amplitude of cast alternatives for equivalent service life

The European Aluminium Association's research demonstrates that 6082-T6 forgings maintain their fatigue properties even after moderate corrosion exposure—a critical consideration for suspension components exposed to road salt and moisture throughout their service life.

7075 and 2024 for High-Stress Applications

When structural requirements exceed what 6xxx alloys can deliver, engineers turn to the 7xxx and 2xxx series. These alloys command higher costs and demand more careful processing, but they provide the strength levels necessary for the most demanding automotive components.

7075 Aluminum is widely recognized as the strongest aluminium alloy commonly available for forging applications. Per industry specifications, 7075 "adds chromium to the mix to develop good stress-corrosion cracking resistance" and serves as "the go-to alloy for aerospace parts, military applications, bicycle equipment, camping and sports gear because of its lightweight yet strong characteristics."

Critical considerations for 7075 in automotive applications:

- Composition: Primary alloying elements are zinc (5.1-6.1%), magnesium (2.1-2.9%), and copper (1.2-2.0%), with chromium for stress-corrosion resistance

- Strength-to-weight ratio: Among the highest available in aluminum alloys—essential for weight-critical performance applications

- Weldability: Poor—this alloy does not weld well and can be quite brittle compared to lower-strength alternatives

- Typical automotive uses: High-stress chassis components, performance wheel applications, racing suspension parts, and components where maximum strength justifies the material premium

For applications requiring similar high-strength performance, engineers sometimes consider alu 7050 as an alternative to 7075. This closely related alloy offers excellent stress-corrosion resistance and toughness, making it particularly valuable for landing gear, structural ribs, and other fatigue-critical applications where 7075's limitations become concerns.

2024 Aluminum brings a different property profile to high-stress applications. This copper-based alloy excels in fatigue resistance—a property that makes it invaluable for components subjected to repeated loading cycles.

According to manufacturing data, 2024 aluminum offers "a high strength-to-weight ratio, excellent fatigue resistance, good machinability, and is heat treatable." However, engineers must account for its limitations: "poor corrosion resistance and is not suitable for welding."

Key 2024 aluminum characteristics include:

- Composition: Copper (3.8-4.9%) is the primary alloying element, with magnesium (1.2-1.8%) and manganese additions

- Fatigue performance: Outstanding resistance to cyclic loading—critical for rotating and reciprocating components

- Machinability: Good, allowing precise finishing of forged blanks

- Typical automotive uses: Pistons, connecting rods, and high-load powertrain components where fatigue resistance outweighs corrosion concerns

2014 Aluminum rounds out the primary forging alloys, offering high strength with better forgeability than some 7xxx alternatives. This alloy finds use in structural applications requiring the copper-based strength profile of the 2xxx series.

Mechanical Property Comparison

Selecting among these grades requires understanding how their mechanical properties compare under equivalent conditions. The following table summarizes relative performance rankings based on industry specifications and manufacturer data:

| Grade | Tensile Strength (T6 Temper) | Yield Strength (T6 Temper) | Elongation | Relative Hardness | Primary Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6061-T6 | Moderate | Moderate | Good (8-10%) | Moderate | Excellent weldability and corrosion resistance |

| 6082-T6 | Moderate-High | Moderate-High | Good (8-10%) | Moderate-High | Superior fatigue performance in corrosive environments |

| 7075-T6 | Very High | Very High | Moderate (5-8%) | High | Highest strength-to-weight ratio |

| 2024-T6 | High | High | Moderate (5-6%) | High | Excellent fatigue resistance |

| 2014-T6 | High | High | Moderate (6-8%) | High | Good forgeability with high strength |

Notice the trade-offs inherent in this comparison. The strongest aluminum alloy options—7075 and the 2xxx grades—sacrifice some ductility and corrosion resistance for their superior strength. Meanwhile, the 6xxx grades deliver a more balanced property profile that suits the majority of automotive structural applications.

When production volumes, cost constraints, and application requirements align, 6082-T6 often emerges as the optimal choice for European-specification suspension and chassis components. For applications demanding maximum strength regardless of other considerations, 7075-T6 delivers. And where fatigue resistance drives the design, 2024 aluminum remains the proven solution.

Understanding these grade-specific characteristics prepares you for the next critical decision: matching each alloy to specific component categories based on their unique performance demands.

Matching Grades to Automotive Component Requirements

You've now explored the essential forged aluminum grades and their mechanical properties. But here's the practical question every engineer and procurement professional asks: which grade belongs in which part of the car? Mapping specific alloys to component categories transforms theoretical knowledge into actionable specifications—and that's exactly what this section delivers.

Think about the diverse demands across a modern vehicle. Suspension arms endure millions of stress cycles over rough roads. Pistons face extreme heat and explosive forces. Wheels must balance strength, weight, and aesthetics. Each component category presents unique challenges that favor certain aluminum grades over others.

Suspension and Chassis Component Grade Selection

Suspension and chassis components represent one of the largest applications for aluminum parts in cars. These parts must absorb road impacts, maintain precise geometry under load, and resist corrosion from road salt and moisture—often simultaneously. The aluminum car frame and related structural elements demand materials that deliver consistent performance across millions of loading cycles.

Control Arms and Suspension Links

Control arms connect the wheel hub to the vehicle chassis, managing both vertical wheel movement and lateral forces during cornering. According to European Aluminium Association documentation, forged control arms made from 6082-T6 have become the standard in European vehicle programs due to their exceptional fatigue performance in corrosive environments.

- 6082-T6: Preferred choice for European OEMs—excellent corrosion resistance combined with superior fatigue life under cyclic loading; maintains properties even after salt spray exposure

- 6061-T6: Cost-effective alternative where weldability is required; slightly lower fatigue performance than 6082 but adequate for many applications

- 7075-T6: Reserved for high-performance and racing applications where maximum strength-to-weight ratio justifies the premium cost and reduced corrosion resistance

Steering Knuckles

Steering knuckles—the pivot points connecting suspension to wheels—face complex multi-directional loading. They must maintain dimensional stability while transmitting steering inputs and supporting vehicle weight. Forged aluminum knuckles typically weigh 40-50% less than cast iron alternatives while offering superior fatigue resistance.

- 6082-T6: Industry standard for production vehicles; the alloy's balanced properties handle the combination of static loads and dynamic forces effectively

- 6061-T6: Suitable for applications requiring post-forging welding or where cost optimization is paramount

- 2014-T6: Considered for heavy-duty applications requiring higher strength than 6xxx alloys can provide

Subframes and Structural Members

When examining what are car bodies made of in modern vehicles, you'll find increasing aluminum content in subframes and structural cross-members. These components form the backbone of vehicle architecture, supporting the powertrain and connecting major suspension attachment points.

- 6061-T6: Excellent choice when subframe design includes welded joints; maintains good properties in heat-affected zones with proper post-weld treatment

- 6082-T6: Preferred for closed-section forged subframe components where corrosion resistance and fatigue performance are critical

Powertrain and Wheel Applications

Powertrain components operate in demanding thermal and mechanical environments that require specialized alloy selection. Meanwhile, wheels must satisfy engineering requirements while meeting aesthetic expectations—a unique combination that shapes material choices.

Pistons

Pistons endure perhaps the most extreme conditions in any engine. Each combustion cycle subjects them to explosive pressure, extreme temperature swings, and high-speed reciprocating motion. According to industry research, aluminum is virtually the only material used for modern pistons, with most produced using gravity die casting or forging.

- 2618 (low-silicon Al-Cu-Mg-Ni alloy): The standard for high-performance forged pistons; maintains strength at elevated temperatures and resists thermal fatigue

- 4032 (eutectic/hypereutectic Al-Si alloy with Mg, Ni, Cu): Offers lower thermal expansion and improved wear resistance for specialized high-temperature applications

- 2024-T6: Selected for racing pistons where fatigue resistance under extreme cyclic loading is the primary design driver

As the reference documentation notes, "Forged pistons made from eutectic or hypereutectic alloys exhibit higher strength and are used in high-performance engines where pistons endure greater stress. Forged pistons with the same alloy composition have a finer microstructure than cast pistons, and the forging process provides greater strength at lower temperatures, allowing for thinner walls and reduced piston weight."

Connecting Rods

Connecting rods transfer combustion forces from piston to crankshaft, experiencing both tensile and compressive loading at high frequencies. According to performance engineering data, material selection depends heavily on the specific engine application.

- 2024-T6: Excellent fatigue resistance makes this the aluminum choice for high-revving naturally aspirated engines where weight reduction is paramount

- 7075-T6: Provides maximum aluminum strength for forced-induction applications, though many builders prefer steel alloys (4340, 300M) for extreme boost levels

For most high-performance applications, the reference material indicates that "Aluminum rods, often reserved for drag racing, provide excellent shock absorption and can handle short bursts of extreme horsepower. Their lightweight nature helps maximize engine acceleration. Yet aluminum's relatively low fatigue resistance and shorter lifespan mean they are unsuitable for daily drivers or endurance racing."

Forged Wheels

Wheels represent a unique intersection of structural engineering and consumer-facing aesthetics. The aluminium car body and wheel combination significantly influences both vehicle performance and buyer perception. Forged wheels offer substantial weight savings over cast alternatives—typically 15-30% lighter—while providing superior strength and impact resistance.

- 6061-T6: Most common choice for production forged wheels; balances strength, formability, and cost-effectiveness; excellent surface finish for aesthetic applications

- 6082-T6: Growing adoption in European wheel programs; slightly higher strength than 6061 with comparable manufacturing characteristics

- 7075-T6: Reserved for motorsport and ultra-premium applications; the highest strength-to-weight ratio justifies significantly higher material and processing costs

The industry data confirms that "A365 is a casting aluminum alloy with good casting properties and high overall mechanical performance, widely used for cast aluminum wheels worldwide." However, forged wheels using 6xxx and 7xxx series alloys deliver superior strength and reduced weight for performance-oriented applications.

Structural Body Components

Modern aluminum body cars increasingly incorporate forged structural nodes and reinforcements within their car aluminum body architecture. These components provide critical load paths and crash energy management in aluminum-intensive vehicle designs.

- 6061-T6: Preferred where components require welding to sheet or extruded aluminum body structures

- 6082-T6: Selected for high-stress nodes in space frame construction; European OEMs favor this grade for integrated structural applications

- 7xxx series: Used selectively for crash-critical components where maximum energy absorption is required

As vehicle architectures evolve toward greater aluminum content, the selection of forged grades for structural applications becomes increasingly important for meeting crash safety requirements while minimizing weight.

With clear grade recommendations now mapped to each component category, the next critical consideration emerges: how heat treatment transforms forged aluminum properties to meet specific performance targets.

Heat Treatment and Temper Selection for Forged Parts

You've selected the right aluminum grade for your automotive component—but your work isn't finished. The heat treatment applied after forging determines whether that carefully chosen alloy delivers its full potential or falls short of expectations. This is where different types of aluminum transform from promising materials into high-performance automotive components.

Sounds complex? Think of heat treatment as the final tuning step that unlocks an alloy's hidden capabilities. Just as a guitar needs proper tuning to produce the right notes, forged aluminum needs precise thermal processing to achieve its specified properties. Understanding aluminum types and properties requires grasping how temper designations define this critical transformation.

T6 Temper for Maximum Strength Applications

When automotive engineers specify maximum strength from heat-treatable aluminum alloys, they almost always call for T6 temper. According to ASM International's documentation on aluminum temper designations, T6 indicates the alloy has been "solution heat treated and, without any significant cold working, artificially aged to achieve precipitation hardening."

What does this two-step process actually involve?

- Solution heat treatment: The forged part is heated to a high temperature—typically 480-540°C depending on the alloy—and held long enough for alloying elements to dissolve uniformly into the aluminum matrix

- Quenching: Rapid cooling, usually in water, locks these dissolved elements in a supersaturated solid solution

- Artificial aging: The part is then held at a moderate temperature (150-175°C for most alloys) for several hours, allowing microscopic strengthening particles to precipitate throughout the metal structure

As technical manufacturing data explains, "T6 heat treatment transforms ordinary aluminum into high-strength components through careful heating and cooling steps. This process creates metals with the perfect balance of strength and workability for many industries."

For automotive applications, T6 delivers the strength levels that suspension arms, wheel hubs, and structural components demand. The documentation confirms that 6061 aluminum, for example, sees its yield strength more than triple—from approximately 55 MPa in the annealed condition to around 275 MPa after T6 treatment.

However, this strength increase comes with a trade-off. Elongation typically drops from about 25% to roughly 12% as the material becomes harder and stronger. For most automotive structural applications, this ductility reduction is acceptable—the components are designed around the T6 property envelope rather than requiring maximum formability.

Alternative Tempers for Specialized Requirements

While T6 dominates automotive forging specifications, several alternative temper designations serve critical roles when application requirements extend beyond maximum strength.

T651 Temper: Stress-Relieved for Dimensional Stability

When you see T651 on an aluminum grades chart, you're looking at T6 properties combined with stress relief. According to the ASM temper designation reference, the "51" suffix indicates the product has been stress relieved by stretching 1.5-3% after quenching but before aging.

Why does this matter for automotive components? Quenching induces significant residual stresses in forged parts. Without stress relief, these internal stresses can cause:

- Dimensional distortion during subsequent machining

- Reduced fatigue life due to additive stress effects

- Increased susceptibility to stress corrosion cracking in certain environments

For precision-machined components like steering knuckles or complex suspension arms, T651 provides the dimensional stability that tight tolerances demand.

T7 Temper: Enhanced Corrosion Resistance

When stress corrosion cracking represents a significant risk—particularly with 7xxx series alloys—engineers specify T7-type tempers. The ASM documentation explains that T7 indicates the alloy has been "solution heat treated and artificially aged to an overaged (past peak strength) condition."

This deliberate overaging sacrifices some strength—typically 10-15% below T6 levels—but dramatically improves resistance to stress corrosion cracking. Two important variants exist:

- T73: Maximum stress corrosion resistance, with approximately 15% lower yield strength than T6

- T76: Enhanced exfoliation corrosion resistance with only 5-10% strength reduction

For high-strength 7xxx alloys used in aerospace-grade automotive components, T7 tempers often represent the optimal balance between strength and long-term reliability in corrosive environments.

T5 Temper: Cost-Effective Processing

T5 temper offers a simplified heat treatment path—the forged part is cooled from the elevated forging temperature and then artificially aged, skipping the separate solution heat treatment step. As industry documentation notes, T5 is "best for medium-strength applications where some flexibility is needed."

While T5 delivers lower strength than T6, it reduces processing costs and cycle times. This makes it suitable for components where maximum strength isn't required—such as certain decorative trim elements or non-structural brackets.

Temper Designation Reference

When consulting an aluminum temper chart or aluminum alloys chart for forged automotive components, you'll encounter these temper designations most frequently:

| Temper | Treatment Process | Resulting Property Changes | Typical Automotive Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| T4 | Solution heat treated, naturally aged at room temperature | Moderate strength, higher ductility than T6, good formability | Components requiring post-forming, intermediate processing stages |

| T5 | Cooled from forging temperature, artificially aged | Medium strength, cost-effective processing, adequate for non-critical parts | Brackets, covers, non-structural components |

| T6 | Solution heat treated, quenched, artificially aged to peak strength | Maximum strength and hardness, reduced ductility compared to T4 | Suspension arms, knuckles, wheels, high-stress structural parts |

| T651 | T6 treatment plus stress relief by stretching (1.5-3%) | T6 properties with improved dimensional stability and reduced residual stress | Precision-machined components, close-tolerance parts |

| T7 | Solution heat treated, overaged beyond peak strength | Slightly lower strength than T6, significantly improved stress corrosion resistance | High-strength alloy components in corrosive environments |

| T73 | Solution heat treated, specifically overaged for maximum SCC resistance | ~15% lower yield than T6, excellent stress corrosion cracking resistance | 7xxx series structural components in demanding environments |

| T76 | Solution heat treated, overaged for exfoliation corrosion resistance | 5-10% lower strength than T6, enhanced exfoliation corrosion resistance | 7xxx series components exposed to humidity and moisture |

Connecting Temper Selection to Performance Requirements

How do you choose the right temper for a specific automotive component? The decision flows from understanding what failure modes the part must resist and what manufacturing constraints exist.

Consider a forged suspension control arm. The component experiences:

- Millions of fatigue loading cycles over vehicle life

- Exposure to road salt and moisture

- Potential stone impact damage

- Precise dimensional requirements for proper suspension geometry

For a 6082 alloy control arm, T6 temper provides the strength and fatigue resistance needed. If the manufacturing process includes significant machining after heat treatment, T651 ensures dimensional stability. The 6xxx alloys' inherent corrosion resistance generally eliminates the need for T7-type overaging.

Now consider a 7075 forged component for a high-performance application. The ultra-high strength of 7075-T6 delivers maximum performance, but the alloy's susceptibility to stress corrosion cracking in the T6 condition may be unacceptable for safety-critical parts. Specifying 7075-T73 reduces peak strength by roughly 15% but provides the stress corrosion resistance necessary for long-term reliability.

The key insight? Temper selection isn't simply about achieving maximum strength—it's about matching the complete property profile to what each component actually requires. This understanding of heat treatment effects prepares you for the manufacturing considerations that determine whether forged aluminum components meet their specifications consistently.

Forging Process Parameters and Manufacturing Considerations

Understanding which aluminum grade suits your component is only half the equation. The other half? Knowing how to actually forge that alloy successfully. Process parameters—temperature ranges, pressure requirements, die heating, and strain rates—vary significantly between aluminum grades. Get these wrong, and even the perfect alloy selection can result in cracked parts, incomplete die filling, or components that fail prematurely in service.

Why do these details matter so much? Unlike aluminium grades for casting where molten metal flows freely into molds, forging requires precise control of solid-state deformation. Each aluminum alloy responds differently to pressure at various temperatures, making process parameter selection critical for structural aluminum applications.

Critical Forging Parameters by Alloy Grade

According to ASM Handbook research on aluminum forging, workpiece temperature is perhaps the most critical process variable. The recommended forging temperature ranges for commonly used automotive grades are surprisingly narrow—typically within ±55°C (±100°F)—and exceeding these limits risks either cracking or inadequate material flow.

Here's what the research reveals about specific alloy families:

- 6061 Aluminum: Forging temperature range of 430-480°C (810-900°F). This alloy demonstrates nearly a 50% decrease in flow stress when forged at the upper temperature limit compared to lower temperatures, making temperature control essential for consistent results.

- 6082 Aluminum: Similar temperature range to 6061. European manufacturers often forge this alloy at temperatures closer to the upper limit to optimize die filling for complex suspension geometries.

- 7075 Aluminum: Narrower forging range of 380-440°C (720-820°F). The 7xxx series displays the least sensitivity to temperature variation, but this also means less margin for error—the alloy won't "forgive" processing mistakes the way more ductile grades will.

- 2014 and 2024 Aluminum: Temperature ranges of 420-460°C (785-860°F). These copper-based alloys require careful preheating control because they're susceptible to deformation heating during rapid forging strokes.

The research emphasizes that "achieving and maintaining proper preheating metal temperatures in the forging of aluminum alloys is a critical process variable that is vital to the success of the forging process." Soak times of 10-20 minutes per inch of section thickness typically ensure uniform temperature distribution before forging begins.

Die Temperature and Strain Rate Effects

Unlike steel forging where dies often remain relatively cool, aluminum forging requires heated dies—and the temperature requirements vary by process type:

| Forging Process/Equipment | Die Temperature Range °C (°F) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Hammers | 95-150 (200-300) | Lower temperatures due to rapid deformation; reduces risk of overheating from adiabatic heating |

| Mechanical Presses | 150-260 (300-500) | Moderate temperatures balance die life with material flow |

| Screw Presses | 150-260 (300-500) | Similar to mechanical presses; excellent for complex aluminum blades |

| Hydraulic Presses | 315-430 (600-800) | Highest temperatures due to slow deformation—isothermal conditions develop |

| Ring Rolling | 95-205 (200-400) | Moderate temperatures maintain metal workability during incremental forming |

Strain rate also significantly influences forging outcomes. The ASM research demonstrates that at a strain rate of 10 s⁻¹ versus 0.1 s⁻¹, the flow stress of 6061 aluminum increases by approximately 70%, while 2014 aluminum nearly doubles its flow stress. This means hammer forging (high strain rates) requires substantially more force than hydraulic press forging (low strain rates) for the same alloy.

For the high-strength 2xxx and 7xxx alloys, rapid strain rate forging equipment like hammers can actually cause problems. The ASM documentation notes that "some high-strength 7xxx alloys are intolerant of the temperature changes possible in rapid strain rate forging, and as a consequence this type of equipment is not employed in the fabrication of forgings in these alloys." Manufacturers often reduce preheating temperatures to the low end of acceptable ranges when using fast equipment to compensate for deformation heating.

Weldability and Assembly Considerations

Once aluminum automotive components are forged and heat treated, many must be joined to create complete vehicle structures. Understanding weldable aluminum grades and their limitations prevents costly assembly failures and ensures structural integrity.

The weldability of forged aluminum grades varies dramatically by alloy family:

- 6061 and 6082: Excellent weldability—these alloys can be joined using conventional MIG and TIG processes with 4043 or 5356 filler metals. However, welding creates a heat-affected zone (HAZ) where the T6 temper properties degrade significantly. According to Lincoln Electric's welding research, post-weld heat treatment may be required to restore strength in critical applications.

- 7075: Poor weldability—this alloy is prone to hot cracking during welding and generally should not be fusion welded. Mechanical fastening or adhesive bonding represents the preferred joining methods for 7075 forged components.

- 2024 and 2014: Limited weldability—while technically weldable, these copper-bearing alloys are susceptible to hot cracking and typically require specialized procedures. Many automotive applications specify mechanical fastening instead.

- 5xxx Series: Excellent weldability—these non-heat-treatable alloys weld readily, though they're less common in forged aluminum automotive components due to lower strength levels.

When welding heat-treatable aluminum forgings like 6061-T6 or 6082-T6, the HAZ can lose up to 40% of its yield strength. Lincoln Electric's research on advanced waveform control technology notes that "variations in chemistry dramatically change an alloy's physical properties" and custom welding waveforms can be designed for specific alloys to minimize these effects.

For critical structural aluminum applications, consider these process strategies:

- Minimize heat input: Use pulsed MIG processes to reduce overall heat transferred to the base metal

- Design for weld location: Position welds away from maximum stress regions when possible

- Specify post-weld treatment: For applications requiring full strength recovery, include solution treatment and aging after welding

- Consider mechanical joining: For high-strength 2xxx and 7xxx forgings, bolted or riveted connections often provide superior reliability

Modern automotive structures increasingly combine forged aluminum nodes with extruded and sheet aluminum components. The joining strategy for these assemblies must account for the different tempers and alloys involved—a forged 6082-T6 suspension mounting point may connect to a 6063-T6 extruded beam using adhesive bonding combined with self-piercing rivets.

With process parameters and weldability considerations understood, the logical next question becomes: how does forged aluminum compare to alternative manufacturing methods for the same components? That comparison reveals when forging truly delivers superior value.

Forged vs Cast vs Billet Aluminum in Automotive Applications

You've explored the essential forged aluminum grades and their manufacturing parameters. But here's a question that procurement professionals and engineers frequently face: should this component even be forged in the first place? Understanding when forging delivers superior value—versus when casting or billet machining makes more sense—can save significant costs while ensuring optimal performance.

The truth is, each manufacturing method exists because it solves specific problems better than the alternatives. When selecting the right material for car body components, powertrain parts, or suspension elements, the manufacturing process matters just as much as the alloy grade. Let's break down exactly how these three approaches compare.

Performance Comparison Across Manufacturing Methods

What actually happens inside the metal during each process? The differences are fundamental—and they directly determine how each component performs in your vehicle.

Forged Aluminum

According to automotive manufacturing research, forging produces parts by "deforming heated metal using pressure, which alters its internal structure and enhances its strength." This process aligns the metal's grain structure, creating a significantly stronger material compared to cast alternatives.

The forging process delivers several distinct advantages:

- Superior mechanical integrity: Grain structure alignment enables forged components to handle greater loads

- Enhanced fatigue resistance: Critical for components enduring millions of stress cycles

- Minimal internal defects: The compression process eliminates voids and porosity common in castings

- Excellent toughness: Ideal for impact-prone applications like wheels and suspension parts

Cast Aluminum

Casting creates components by pouring molten aluminum into molds and allowing it to solidify. As manufacturing analysis explains, this process "enables complex shapes through controlled solidification" and offers unmatched design flexibility.

When evaluating cast aluminum grades and die cast aluminum alloys, consider these characteristics:

- Complex geometry capability: Intricate internal passages and detailed features are achievable

- Lower tooling costs for complex parts: Casting molds often cost less than forging dies for equivalent complexity

- Porosity risk: Trapped gases can create internal voids that compromise strength

- Variable mechanical properties: Aluminum alloy castings exhibit more property variation than forged equivalents

The research notes that advances in high-pressure die casting have considerably improved aluminum alloy castings quality, "making it possible to create components that are both lightweight and durable." However, for safety-critical applications, the inherent limitations of the casting process remain relevant.

Billet Aluminum

Billet machining starts with solid aluminum stock—typically extruded or rolled—and removes material using CNC equipment to create the final geometry. According to industry documentation, this approach "allows for tight tolerances, making it ideal for high-performance parts."

Key billet characteristics include:

- Maximum precision: CNC machining achieves tolerances that casting and forging cannot match directly

- Consistent grain structure: Starting material has uniform properties throughout

- High material waste: Significant aluminum is machined away, increasing effective material costs

- No tooling investment: Programming changes replace physical die modifications

Manufacturing Method Comparison

| Criteria | Forged Aluminum | Cast Aluminum | Billet Aluminum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strength | Highest—aligned grain structure maximizes mechanical properties | Lower—grain structure is random; potential porosity weakens material | High—consistent base material, but machining removes favorable grain flow |

| Weight Optimization | Excellent—strength allows thinner walls while maintaining performance | Good—complex shapes enable material placement optimization | Moderate—limited by starting stock geometry and machining constraints |

| Unit Cost | Moderate to high—depends on complexity and volume | Low for high volumes—tooling amortizes over large production runs | High—significant machine time and material waste per part |

| Tooling Investment | High—precision forging dies require significant upfront investment | Moderate to high—varies by casting method and complexity | Low—CNC programming replaces physical tooling |

| Production Volume Suitability | Medium to high volumes—tooling investment favors larger runs | High volumes—die casting excels at mass production | Low volumes—ideal for prototypes and specialty parts |

| Design Complexity | Moderate—limited by die design and material flow constraints | High—internal passages and intricate features are achievable | Very high—virtually any geometry that CNC tooling can reach |

| Typical Automotive Applications | Suspension arms, wheels, connecting rods, steering knuckles | Engine blocks, transmission housings, intake manifolds | Prototype parts, low-volume performance components, custom brackets |

When Forging Delivers Superior Value

Given the trade-offs outlined above, when does forging emerge as the clear winner? The decision criteria become straightforward once you understand what each application truly demands.

Choose forging when:

- Fatigue resistance is critical: Components experiencing repeated loading cycles—suspension arms, wheels, connecting rods—benefit most from forging's aligned grain structure. The research confirms that forged parts "tend to have superior fatigue resistance and toughness," making them "especially suitable for performance-oriented vehicles."

- Maximum strength-to-weight ratio matters: Among metals used in cars bodies and structural applications, forged aluminum achieves the highest strength with minimum weight. When every gram counts for performance or efficiency, forging justifies its premium.

- Production volumes justify tooling: For annual volumes exceeding several thousand units, forging die investment amortizes effectively. Below this threshold, billet machining may prove more economical despite higher per-part costs.

- Safety-critical applications demand reliability: The absence of internal porosity in forgings provides confidence that cast alternatives cannot match. For components where failure consequences are severe, forging's consistent quality reduces risk.

Consider alternatives when:

- Complex internal geometries are required: Casting enables passages and chambers that forging cannot create. Engine blocks and transmission housings exemplify where casting's design flexibility proves essential.

- Volumes are extremely high: For commodity components produced in millions annually, die casting's per-unit economics become compelling despite lower strength.

- Prototype or low-volume production: Billet machining eliminates tooling investment entirely, making it ideal for development parts or specialty applications with volumes below economical forging thresholds.

- Aesthetic surfaces are paramount: Cast and machined surfaces often require less finishing for decorative applications than as-forged surfaces.

The automotive industry's material for car body selection increasingly reflects these trade-offs. High-stress structural nodes often use forged aluminum, while complex housings rely on advanced casting techniques, and prototype programs leverage billet machining for rapid development.

Understanding when forging outperforms alternatives helps you specify the right process from the start. But even with this knowledge, grade selection mistakes still occur—and knowing how to avoid them, or how to substitute grades when needed, can prevent costly manufacturing problems.

Grade Substitution and Selection Best Practices

Even with perfect knowledge of aluminum alloy properties and forging parameters, real-world manufacturing presents unexpected challenges. Supply chain disruptions, material availability issues, or cost pressures sometimes force engineers to consider alternatives to their preferred aluminum grade. Knowing which substitutions work—and which create problems—separates successful programs from costly failures.

Beyond substitution scenarios, many grade selection mistakes occur simply because engineers apply steel-design thinking to aluminum structures. Understanding these common pitfalls helps you avoid expensive rework and component failures before they happen.

Grade Substitution Guidelines

When your specified aluminum alloy becomes unavailable, resist the temptation to simply grab the next option on the list. Different grades of aluminum behave differently under forging, heat treatment, and service conditions. Successful substitutions require matching the most critical performance requirements while accepting trade-offs in secondary characteristics.

Here are proven substitution pairs for common automotive forging grades:

- 6082 → 6061: The most common substitution in automotive forging. Expect slightly lower yield strength (approximately 5-10% reduction) and somewhat reduced fatigue performance in corrosive environments. Both alloys share excellent weldability and corrosion resistance. Acceptable for most suspension and structural applications where 6082 was specified primarily for availability reasons rather than marginal strength advantages.

- 6061 → 6082: Works well when material is available—6082 actually provides slightly better strength. No significant property downgrades, though 6082 may cost more depending on regional availability. European supply chains often favor 6082, while North American sources typically stock 6061 more readily.

- 7075 → 7050: Both deliver ultra-high strength, but 7050 offers improved stress corrosion cracking resistance and better toughness. This substitution often represents an upgrade rather than a compromise. Expect similar or slightly lower peak strength with improved fracture toughness.

- 7075 → 2024: Use cautiously—while both are high-strength alloys, their property profiles differ significantly. 2024 provides excellent fatigue resistance but lower ultimate strength than 7075. Suitable when cyclic loading dominates the design case, but not when maximum static strength is required.

- 2024 → 2014: Both copper-based alloys with similar forging characteristics. 2014 offers slightly better forgeability with comparable strength. Acceptable for most powertrain applications where 2024 was originally specified.

- 6061 → 5083: Generally not recommended for forged components. While 5083 offers excellent corrosion resistance, it's not heat-treatable and cannot achieve the strength levels of 6061-T6. Only consider this substitution for non-structural applications where corrosion resistance outweighs strength requirements.

When evaluating any substitution, verify that the alternative grade meets all critical specifications—including forging temperature compatibility, heat treatment response, and any downstream assembly requirements like weldability. A grade that works metallurgically may still fail if your production equipment cannot process it properly.

Avoiding Common Selection Mistakes

According to Lincoln Electric's engineering guidance, one of the most frequent aluminum design errors is simply selecting the strongest available alloy without considering other critical factors. As their technical documentation states: "Very often, the designer will choose the very strongest alloy available. This is a poor design practice for several reasons."

Why does choosing the strongest aluminium alloy sometimes backfire?

- Deflection often governs design, not strength: The elastic modulus of most aluminum alloys—weak and strong alike—is approximately the same (one-third that of steel). If your component's critical limit is stiffness rather than yield strength, paying a premium for 7075 over 6061 gains you nothing.

- Many high-strength alloys are not weldable: The Lincoln Electric research emphasizes that "many of the strongest aluminum alloys are not weldable using conventional techniques." Specifying 7075 for a component that must be welded into a larger assembly creates manufacturing impossibilities. The documentation specifically notes that 7075 "should never be welded for structural applications."

- Weld zone properties differ from base material: Even with weldable grades like 6061, "the weld will rarely be as strong as the parent material." Designing around T6 base material properties while ignoring heat-affected zone degradation leads to undersized welds and potential failures.

Here are additional selection mistakes to avoid:

- Specifying strain-hardened tempers for welded assemblies: For non-heat-treatable alloys (1xxx, 3xxx, 5xxx), welding acts as a local annealing operation. "No matter what temper one starts with, the properties in the HAZ will be those of the O temper annealed material," the research confirms. Buying expensive strain-hardened material that will be welded wastes money—the HAZ reverts to annealed properties regardless.

- Ignoring post-weld treatment requirements: Heat-treatable alloys like 6061-T6 experience significant strength degradation in the weld zone. The research shows that "the minimum as-welded tensile strength of 24 ksi" compares to "40 ksi" for the T6 base material—a 40% reduction. Failing to specify post-weld aging when strength recovery is needed compromises structural integrity.

- Overlooking stress corrosion susceptibility: High-strength 7xxx alloys in T6 temper can be susceptible to stress corrosion cracking. Specifying 7075-T6 for components exposed to moisture and sustained loading without considering T73 or T76 tempers risks premature field failures.

- Confusing casting alloys with forging alloys: Some specifications incorrectly call out aluminium grades for casting when forged components are required. A356 and A380 are excellent die casting alloys but are not suitable for forging—their chemistry is optimized for fluidity in the molten state, not solid-state deformation.

Working with Qualified Forging Partners

Many grade selection challenges become manageable when you work with experienced forging suppliers who understand automotive requirements. Specialty alloys for automotive applications often require precise process control that only established manufacturers can provide consistently.

When evaluating potential forging partners, consider their engineering support capabilities. Can they advise on optimal grade selection for your specific component? Do they have experience with the tempers and post-forge treatments your application requires? IATF 16949-certified manufacturers like Shaoyi bring the quality systems and technical expertise that help translate grade selection decisions into reliable production components.

Their rapid prototyping capabilities—delivering initial parts in as little as 10 days—allow you to validate grade selections before committing to high-volume production tooling. For components like suspension arms and drive shafts where aluminum quality directly impacts vehicle safety, having engineering partners who understand both metallurgy and automotive requirements proves invaluable.

The combination of proper grade selection knowledge and qualified manufacturing partnerships creates the foundation for successful forged aluminum programs. With these elements in place, you're prepared to make final material decisions that balance performance requirements, manufacturing constraints, and cost considerations effectively.

Selecting the Right Forged Aluminum Grade for Your Application

You've now explored the complete landscape of forged aluminum grades for cars—from understanding alloy series designations through matching specific grades to component requirements, and from heat treatment considerations to manufacturing parameters. But how do you pull all this knowledge together into actionable decisions? Let's distill the essential guidance that transforms technical understanding into successful procurement outcomes.

Whether you're specifying aluminum for cars in a new vehicle program or optimizing an existing supply chain, the grade selection process follows a logical sequence. Getting this sequence right prevents costly mistakes and ensures your aluminum automotive parts deliver the performance your vehicles demand.

Key Takeaways for Grade Selection

After examining the full spectrum of car aluminum options, several decision factors consistently determine success:

- Start with stress requirements, not material preferences: Define what your component actually experiences—static loads, cyclic fatigue, impact forces, or combinations thereof. A suspension arm enduring millions of road cycles demands different properties than a bracket seeing only static loads. Match the alloy family to these real-world demands: 6xxx for balanced performance, 7xxx for maximum strength, 2xxx for superior fatigue resistance.

- Factor in manufacturing volume early: Forging economics favor medium to high production volumes where tooling investment amortizes effectively. For volumes below several thousand annually, validate that forging remains cost-competitive against billet machining alternatives. High-volume programs benefit most from forging's combination of superior properties and efficient production.

- Account for downstream processing: If your component requires welding into a larger assembly, this single requirement eliminates entire alloy families from consideration. Specify 6061 or 6082 when weldability matters; avoid 7075 for any structural welded application. Similarly, consider post-forge machining requirements—T651 tempers provide the dimensional stability that precision machining demands.

- Evaluate total cost, not just material price: The cheapest aluminium for cars isn't always the most economical choice. A premium alloy that enables thinner walls, reduced finishing, or simplified heat treatment may deliver lower total component cost than a cheaper grade requiring additional processing. Calculate the complete picture before finalizing specifications.

- Build supply chain resilience: Identify acceptable substitution grades before production begins. Knowing that 6061 can substitute for 6082—or that 7050 provides an upgrade path from 7075—gives you options when supply disruptions occur. Document these alternatives in your specifications so procurement teams can respond quickly to availability changes.

The most critical selection principle: choose the alloy that best matches your component's actual performance requirements—not the strongest available option. Overspecification wastes money and can create manufacturing complications, while underspecification risks field failures that damage both vehicles and reputations.

Partnering for Automotive Forging Success

Here's the reality that every experienced engineer understands: even perfect grade selection means nothing without a manufacturing partner capable of executing consistently. The gap between material specification and quality components requires expertise that only qualified forging suppliers can bridge.

When aluminum in cars must meet demanding performance standards, supplier selection becomes as critical as alloy selection. According to industry guidance on evaluating forging suppliers, three factors matter most: certifications and quality systems, production capabilities and equipment, and rigorous quality control standards.

For automotive applications specifically, IATF 16949 certification demonstrates that a supplier has implemented the quality management systems the automotive industry demands. This certification—building on ISO 9001 foundations with automotive-specific requirements—validates that the manufacturer understands traceability, process control, and continuous improvement at the level your vehicle programs require.

Beyond certification, evaluate practical capabilities that translate specifications into parts:

- Engineering support: Can the supplier advise on optimal grade selection for your specific geometry and loading conditions? Do they understand heat treatment implications and can recommend appropriate tempers?

- Prototyping speed: Modern vehicle development timelines demand rapid iteration. Partners offering prototype forgings in compressed timeframes—some as fast as 10 days—enable design validation before committing to production tooling.

- Component expertise: Suppliers with demonstrated experience in your component category—whether suspension arms, drive shafts, or structural nodes—bring application-specific knowledge that general forging houses may lack.

- Quality control infrastructure: Advanced inspection technologies, in-process monitoring, and comprehensive documentation systems ensure that every component meets specification. The reference materials emphasize that leading suppliers invest in coordinate measuring machines, non-destructive testing equipment, and material analysis capabilities.

For engineers and procurement professionals seeking aluminium cars component manufacturing, Shaoyi (Ningbo) Metal Technology exemplifies the partner profile that successful programs require. Their IATF 16949 certification validates automotive-grade quality systems, while their in-house engineering team provides the technical guidance that helps translate grade selection decisions into production-ready specifications. Located near Ningbo Port, they combine rapid prototyping capabilities—with initial parts available in as little as 10 days—alongside high-volume mass production capacity for mature programs.

Their demonstrated expertise with demanding aluminum automotive parts like suspension arms and drive shafts reflects the component-specific knowledge that makes grade selection guidance actionable. When specifications call for 6082-T6 control arms or 7075-T6 performance components, having a manufacturing partner who understands both the metallurgy and the automotive quality requirements ensures that material selection translates into reliable components.

The journey from alloy specification to vehicle performance runs through manufacturing execution. By combining the grade selection knowledge you've gained throughout this guide with qualified forging partners who share your commitment to quality, you position your automotive programs for success—delivering the strength, weight savings, and reliability that modern vehicles demand from their forged aluminum components.

Frequently Asked Questions About Forged Aluminum Grades for Cars

1. What are the grades of aluminum forging?

The most commonly forged aluminum grades for automotive applications include 6061, 6063, 6082 from the 6000 series, and 7075 from the 7000 series. The 6xxx alloys offer excellent forgeability, corrosion resistance, and balanced strength, making them ideal for suspension arms and wheels. The 7xxx series delivers ultra-high strength for performance-critical components. Additionally, 2024 and 2014 from the 2xxx series provide superior fatigue resistance for powertrain parts like pistons and connecting rods. IATF 16949-certified manufacturers like Shaoyi can guide optimal grade selection based on specific component requirements.

2. What grade of aluminium is used in cars?

Automotive applications utilize multiple aluminum grades depending on component requirements. Common grades include 1050, 1060, 3003, 5052, 5083, 5754, 6061, 6082, 6016, 7075, and 2024. For forged components specifically, 6082-T6 dominates European suspension and chassis applications due to excellent fatigue performance in corrosive environments. 6061-T6 remains popular in North America for its weldability. High-performance applications often specify 7075-T6 for maximum strength-to-weight ratio, while 2024-T6 excels in fatigue-critical powertrain components.

3. Is 5052 or 6061 aluminum stronger?

6061 aluminum is significantly stronger than 5052. In the T6 temper, 6061 achieves tensile strength around 310 MPa compared to 5052's approximately 220 MPa. However, strength isn't everything—5052 offers superior corrosion resistance and better formability since it's a non-heat-treatable alloy. For forged automotive components requiring structural integrity, 6061-T6 is preferred because it can be heat-treated to achieve higher strength levels essential for suspension arms, wheels, and chassis components.

4. What is the difference between forged and cast aluminum wheels?

Forged aluminum wheels are created by compressing heated aluminum under extreme pressure, aligning the grain structure for superior strength and fatigue resistance. Cast wheels are made by pouring molten aluminum into molds, resulting in random grain structure and potential porosity. Forged wheels typically weigh 15-30% less than cast equivalents while offering better impact resistance and durability. For performance vehicles, forged 6061-T6 or 7075-T6 wheels deliver the strength-to-weight ratio that cast alternatives cannot match.

5. How do I choose the right aluminum grade for automotive forging?

Start by defining your component's actual stress requirements—static loads, cyclic fatigue, or impact forces. For balanced structural applications, 6xxx alloys like 6082-T6 or 6061-T6 offer excellent performance. When maximum strength is critical, specify 7075-T6. For superior fatigue resistance in powertrain parts, consider 2024-T6. Factor in weldability needs (6xxx alloys weld well; 7075 does not), production volumes, and heat treatment requirements. Working with experienced forging partners like Shaoyi, who offer rapid prototyping and IATF 16949 certification, helps validate grade selections before committing to production tooling.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —