Die Galling Prevention in Stamping: Engineering Solutions for Adhesive Wear

TL;DR

Die galling in stamping is a destructive form of adhesive wear, often called "cold welding," where the tool and workpiece fuse at a microscopic level due to excessive friction and heat. Prevention requires a multi-layered engineering approach rather than a single quick fix. The three primary lines of defense are: optimizing die design by increasing punch-to-die clearance in thickening zones (like draw corners), selecting dissimilar tool materials (such as Aluminum Bronze) to break chemical affinity, and applying advanced coatings like TiCN or DLC only after the surface is perfectly polished. Operational adjustments, such as using Extreme Pressure (EP) lubricants and reducing press speed, serve as final countermeasures.

The Physics of Galling: Why Cold Welding Occurs

To prevent die galling, one must first understand that it is fundamentally different from abrasive wear. While abrasive wear is like sanding wood with coarse paper, galling is a phenomenon of adhesive wear. It occurs when the protective oxide layers on metal surfaces break down under the immense pressure of the stamping press. When this happens, the chemically active "virgin" metal of the workpiece comes into direct contact with the tool steel.

At a microscopic level, surfaces are never perfectly smooth; they consist of peaks and valleys known as asperities. Under high tonnage, these asperities interlock and generate intense localized heat. If the two metals have a chemical affinity—such as stainless steel and D2 tool steel, which both contain high amounts of chromium—they can atomically bond. This process is known as surface-to-surface migration or cold welding. As the tool continues to move, these welded bonds shear, tearing chunks of material from the softer surface and depositing them onto the harder tool. These deposits, or "galls," then act as plowshares, causing catastrophic scoring on subsequent parts.

First Line of Defense: Die Design & Geometry

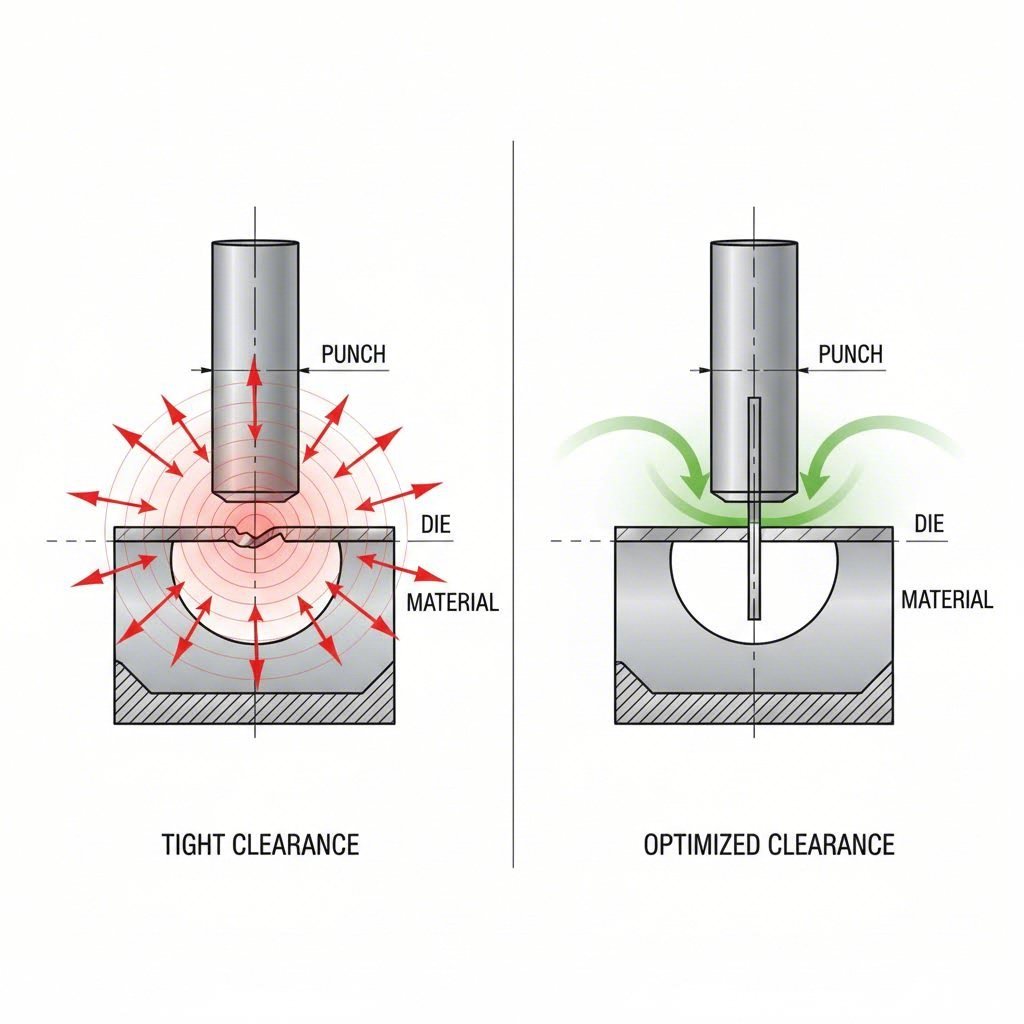

The most common misconception in the industry is that coatings can fix any wear problem. However, industry experts caution that if the root cause is mechanical, applying a coating merely "coats the problem." The primary mechanical culprit is often insufficient punch-to-die clearance, particularly in deep-drawn parts.

In deep drawing, the sheet metal undergoes in-plane compression as it flows into the die cavity, which causes the material to naturally thicken. If the die design does not account for this thickening—especially in the vertical walls of draw corners—the clearance disappears. The die effectively "pinches" the material, creating massive friction spikes that no amount of lubricant can overcome. According to MetalForming Magazine, a critical preventive measure is to machine additional clearance (often 10–20% of material thickness) into these thickening zones.

For complex production runs, such as automotive control arms or subframes, predicting these thickening zones requires sophisticated engineering. This is where partnering with specialized manufacturers becomes a strategic advantage. Companies like Shaoyi Metal Technology leverage advanced CAE analysis and IATF 16949-certified protocols to engineer these clearance allowances into the die design phase, ensuring that high-volume automotive stamping remains gall-free from the first stroke.

Another geometric factor is the polishing direction. Tool and die makers should polish die sections parallel to the direction of the punching or drawing motion. Cross-polishing leaves microscopic grooves that act as abrasive files against the workpiece, accelerating the breakdown of the lubricant film.

Material Science: The "Dissimilar Metals" Strategy

When stamping stainless steel or high-strength alloys, the choice of tool steel is critical. A common failure mode involves using D2 tool steel to stamp stainless steel. Since D2 contains roughly 12% chromium and stainless steel also relies on chromium for corrosion resistance, the two materials have a high "metallurgical compatibility." They want to stick together.

The solution is to use dissimilar metals to break this chemical affinity. For severe galling applications, engineering bronze materials, specifically Aluminum Bronze, are often superior to conventional tool steels. Although Aluminum Bronze is softer than steel, it possesses excellent lubricity and thermal conductivity, and crucially, it refuses to cold-weld to ferrous substrates. Using Aluminum Bronze inserts or bushings in high-friction areas can eliminate adhesive wear where harder materials fail.

If tool steel is required for toughness, consider Powder Metallurgical (PM) grades (like CPM 3V or M4). These offer a finer carbide distribution than conventional D2, providing a smoother surface that is less prone to initiating the adhesive wear cycle.

Advanced Surface Treatments & Coatings

Once the mechanics and materials are optimized, surface coatings provide the final barrier. Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) coatings are standard for modern stamping, but selecting the right chemistry is vital.

- TiCN (Titanium Carbonitride): An excellent general-purpose coating that offers higher hardness and lower friction than standard TiN. It is widely used for forming high-strength steels.

- DLC (Diamond-Like Carbon): Known for its extremely low coefficient of friction, DLC is the premium choice for aluminum and difficult non-ferrous applications. It mimics the properties of graphite, allowing the workpiece to slide with minimal resistance.

- Nitriding: A diffusion process rather than a coating, nitriding hardens the surface of the tool steel itself. It is often used as a base treatment before applying PVD coatings to prevent the "eggshell effect," where a hard coating cracks because the substrate underneath creates a soft spot.

Critical Warning: A coating is only as good as the substrate preparation. The tool surface must be polished to a mirror finish before coating. Any existing scratches or asperities will simply be reproduced by the coating, creating hard, sharp peaks that will aggressively attack the workpiece.

Operational Countermeasures: Lubrication & Maintenance

On the shop floor, operators can mitigate galling risks through disciplined process control. The first variable is lubrication. For galling prevention, simple oils are often insufficient. The process requires lubricants with Extreme Pressure (EP) additives (such as sulfur or chlorine) or solid barriers (like graphite or molybdenum disulfide). These additives form a "tribological film" that separates the metals even when the liquid oil is squeezed out by tonnage.

Heat management is the second operational lever. Galling is thermally activated; higher temperatures soften the workpiece and encourage bonding. If galling appears, try reducing the press speed (strokes per minute). This lowers the process temperature and gives the lubricant more time to recover between hits. Rolleri also suggests adopting a "bridge" slitting sequence for punching operations, which alternates hits to prevent localized heat buildup and material accumulation.

Finally, routine maintenance must be proactive. Do not wait for a gall to appear. Implement a schedule to stone and clean die radii, removing microscopic pickup before it grows into a damaging lump. Sharp tools reduce the tonnage required to form the part, thereby reducing the friction and heat that drive the galling mechanism.

Engineering Reliability Into the Process

Preventing die galling is not a matter of luck; it is a discipline of physics and engineering. By respecting the laws of friction—providing adequate clearance for material flow, choosing chemically incompatible materials, and maintaining a barrier film of lubricant—manufacturers can virtually eliminate cold welding. The cost of upfront design analysis and premium materials is minuscule compared to the downtime of a seized die or the scrap rate of scored parts. Treat the root cause, not the symptom, and production reliability will follow.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How do you reduce galling in stamping dies?

To reduce galling, focus on three areas: Mechanics, Materials, and Lubrication. First, ensure the punch-to-die clearance is sufficient (adding 10-20% extra in thickening zones). Second, use dissimilar metals like Aluminum Bronze or coated PM steels to prevent cold welding. Third, use high-viscosity lubricants with Extreme Pressure (EP) additives to maintain a barrier film under load.

2. Does anti-seize prevent galling?

Yes, anti-seize compounds can prevent galling by introducing solid lubricants (like copper, graphite, or molybdenum) between the surfaces. These solids provide a physical barrier that keeps the mating metals apart even when high pressure squeezes out liquid oils. However, anti-seize is a localized operational fix and does not correct underlying design flaws like tight clearance.

3. What is the primary cause of galling?

The primary cause of galling is adhesive wear driven by friction and heat. When high pressure breaks the protective oxide film on metal surfaces, the exposed atoms can bond or "weld" together. This is most common when the tool and workpiece have similar chemical compositions (e.g., stamping stainless steel with uncoated tool steel), leading to high metallurgical affinity.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —