Curling Process in Metal Stamping: Mechanics, Tooling & Design

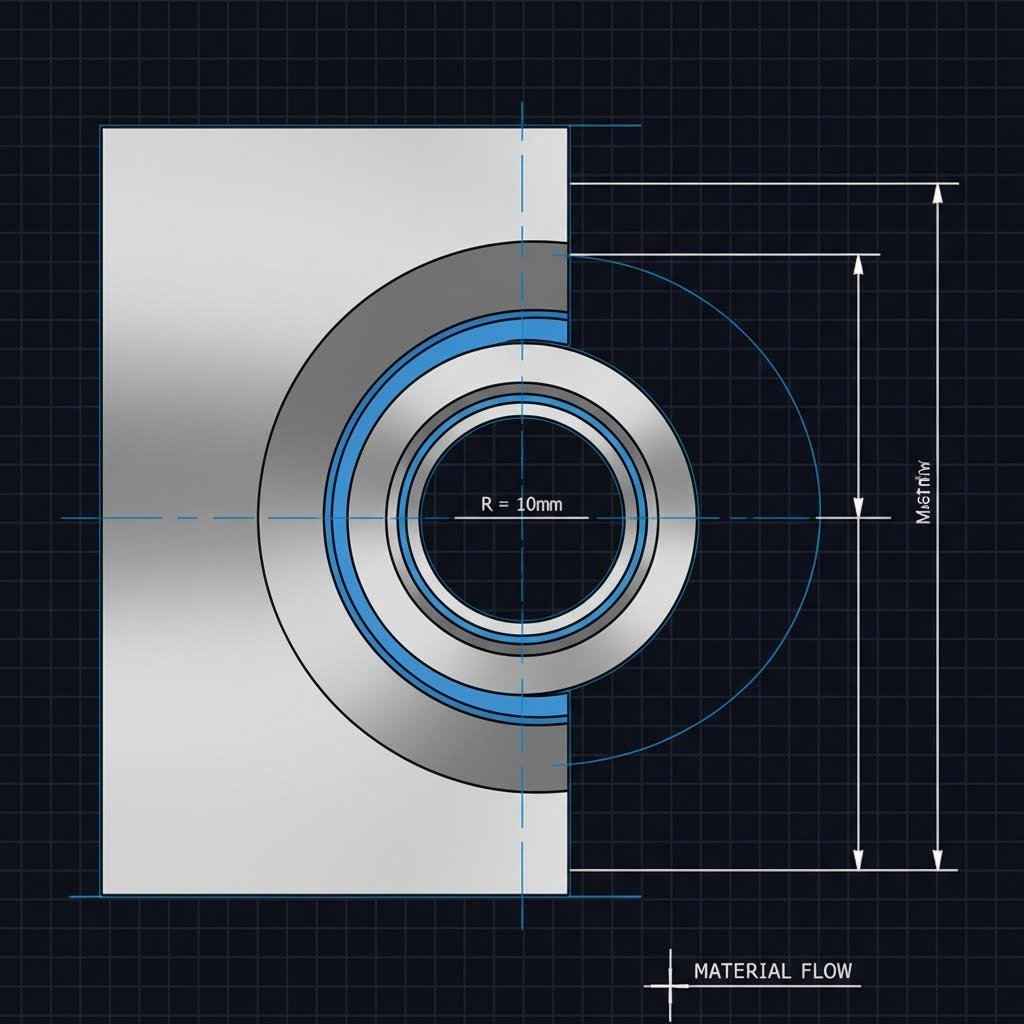

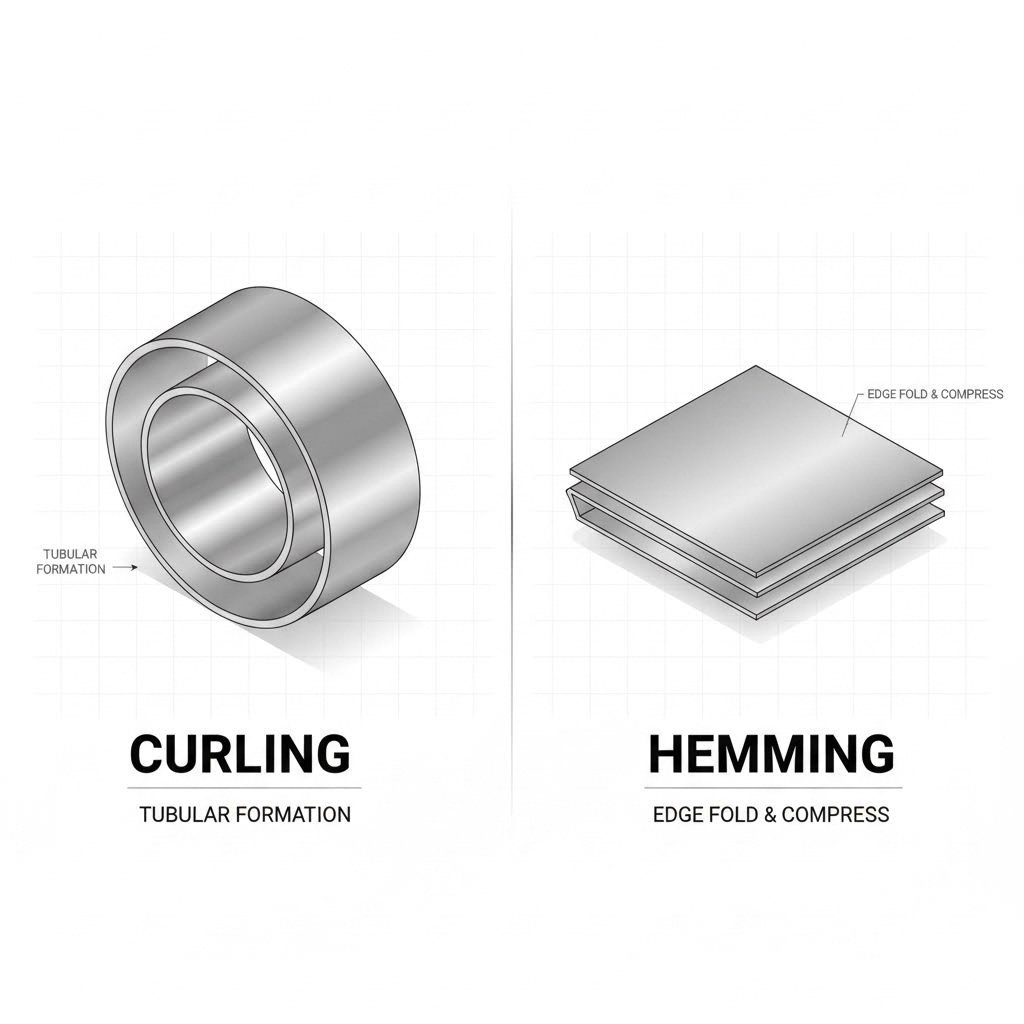

<h2>TL;DR</h2><p>The <strong>curling process in metal stamping</strong> is a precision forming operation that rolls the edge of a sheet metal workpiece into a hollow, circular ring. Unlike simple bending, curling hides the raw edge inside the roll, creating a safe, smooth finish while significantly increasing the part's structural stiffness (moment of inertia). Common examples include door hinges, handle grips, and the reinforced rims of metal cups, where both safety and rigidity are critical.</p><h2>What is Curling in Metal Stamping?</h2><p>Curling is a sheet metal forming method used to create a hollow, circular roll at the edge of a workpiece. This process is distinct from other edge-finishing techniques because it forces the material to roll back upon itself, enclosing the cut edge completely. The result is a tubular radial profile that serves two primary engineering purposes: it eliminates sharp, dangerous burrs created during the blanking stage, and it adds substantial rigidity to otherwise flimsy sheet metal without increasing the material's gauge.</p><p>It is crucial to distinguish curling from <strong>hemming</strong> or <strong>teardrop hemming</strong>. While a hem folds the metal flat against itself (often leaving the raw edge exposed or merely tucked), a curl maintains a circular cross-section. According to tooling experts at <a href="https://sheetmetal.me/tooling-terminology/curling/">SheetMetal.Me</a>, the defining characteristic of a curl is that the edge finishes <em>inside</em> the roll. This geometry is what generates the superior stiffness known as the "moment of inertia," making the curled edge highly resistant to bending forces.</p><p>Curling can be applied to both flat sheets (linear curling) and round parts (rotary curling). A classic real-world example is the standard door hinge, where the metal is curled to create the housing for the hinge pin. The process transforms a flat strip into a functional, load-bearing mechanical feature.</p><h2>The Mechanics of the Curling Process</h2><p>The physics of curling involves feeding the sheet metal edge into a specially shaped die cavity that forces the material to follow a circular path. As the punch pushes the metal into the die, the leading edge hits a smooth radius and begins to turn upwards and inwards. This deformation continues until the edge completes the circle (or partial circle) and tucks inside itself.</p><p>One of the most critical technical rules in curling mechanics concerns <strong>burr orientation</strong>. As noted in <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curling_(metalworking)">Wikipedia's technical overview</a>, the burr (the rough, raised edge left by the initial cutting process) should always be turned <em>away</em> from the die radius. If the sharp burr drags against the curling die's surface, it causes premature wear, scratching, and galling (material adhesion), which destroys the tool's finish and ruins part quality.</p><p>Engineers also categorize curls based on the position of the roll's center relative to the sheet:</p><ul><li><strong>Off-Center Curl:</strong> The center of the circular roll sits above the plane of the sheet metal. This is easier to form as the material naturally wants to lift.</li><li><strong>On-Center Curl:</strong> The center of the roll is perfectly aligned with the sheet's plane. This is geometrically more demanding and often requires more complex, multi-stage tooling to force the material downwards before it curls up.</li></ul><h2>Tooling and Die Design Considerations</h2><p>Successful curling requires high-precision tooling designed to manage the high friction and stress of the operation. The curling dies are typically manufactured from <strong>hardened tool steel</strong> to withstand the abrasive nature of the metal sliding against the cavity. To ensure a uniform curl and prevent the material from sticking, the die cavities must be lapped and polished to a mirror finish.</p><p>For consistent production, simply pushing metal into a groove is rarely enough. Most robust curling operations utilize a <strong>three-stage tooling approach</strong>. The first two stages pre-form the initial curves (often called the "start"), while the third stage closes the curl into its final circular shape. A <strong>locating notch</strong> or stop block is essential in the die design to align the workpiece precisely; if the sheet enters the die at a slight angle, the curl will spiral (corkscrew) rather than close perfectly.</p><p>Die designers must also account for <strong>springback</strong>—the metal's tendency to return to its original shape after forming. To compensate, the curling die is often designed to slightly "over-bend" the material, ensuring that when it relaxes, it settles into the correct diameter. Without this compensation, the curl may end up loose or open, failing to capture the raw edge securely.</p><h2>Applications and Strategic Benefits</h2><p>The decision to use the curling process is usually driven by safety, strength, and aesthetics. By burying the sharp edge inside the roll, manufacturers make parts safe for handling without the need for secondary grinding or deburring operations. This is vital in consumer goods like stainless steel mixing bowls, pots, and metal furniture handles.</p><p>Structurally, curling acts like a stiffening rib. It dramatically increases the moment of inertia along the edge, allowing engineers to use thinner, lighter, and cheaper gauge materials while maintaining the part's rigidity. This is particularly valuable in the automotive industry for panels and structural components where weight reduction is a priority.</p><p>For high-volume automotive applications requiring such precision—like control arms or subframes—manufacturers often rely on specialized partners to manage the complex tooling transitions. <a href="https://www.shao-yi.com/auto-stamping-parts/">Shaoyi Metal Technology</a>, for instance, offers IATF 16949-certified stamping services that scale from rapid prototyping to mass production, ensuring that critical features like curled edges meet global OEM standards for safety and durability.</p><h2>Troubleshooting Common Defects</h2><p>Despite being a standard operation, curling is prone to specific defects if process variables aren't controlled. Understanding these failure modes is key to maintaining quality:</p><ul><li><strong>Uneven or Spiraling Curls:</strong> Usually caused by misalignment. If the blank is not firmly held against the locating notch, the material feeds unevenly into the radius. Increasing the clamping pressure or adjusting the back gauge often resolves this.</li><li><strong>Material Cracking:</strong> Occurs when the curl radius is too tight for the material's ductility. Harder metals (like certain aluminum alloys or high-strength steels) generally require a larger curl radius to prevent fracturing on the outer tension surface.</li><li><strong>Galling and Scoring:</strong> As mentioned in the mechanics section, this is often due to the burr facing the die. Alternatively, it indicates a lack of lubrication or a degraded die finish. Regular polishing of the die cavity and proper lubricant application are mandatory preventative maintenance.</li><li><strong>Part Deformation:</strong> If the main body of the part buckles while the edge is being curled, the unsupported area is too large. Support blocks or pressure pads must be added to hold the flat portion of the part rigid while the edge is being formed.</li></ul><h2>Summary</h2><p>The curling process transforms a simple sheet metal edge into a robust, safe, and functional feature. By understanding the interaction between burr orientation, material ductility, and die polish, manufacturers can produce high-quality curls that enhance both the utility and longevity of stamped components. Whether for a simple hinge or a complex automotive assembly, success lies in the precision of the die design and the control of the forming mechanics.</p><section><h2>Frequently Asked Questions</h2><h3>1. What is the difference between curling and hemming?</h3><p>Curling rolls the edge into a hollow, circular ring where the raw edge is tucked inside the roll. Hemming folds the metal flat against itself, which doubles the thickness but typically leaves the edge exposed or flattened rather than rounded. Curling provides greater stiffness (moment of inertia) compared to a flat hem.</p><h3>2. Why is the burr orientation important in curling?</h3><p>The burr (the sharp, raised edge from cutting) should always be oriented <em>away</em> from the curling die. If the burr faces the die, it acts like a cutting tool, scratching the polished die surface and causing galling, which ruins both the tool and the finish of subsequent parts.</p><h3>3. Can you curl any type of metal?</h3><p>Most ductile metals like mild steel, stainless steel, aluminum, and copper can be curled. However, materials with low ductility or high hardness may crack if the curl radius is too tight. The tooling design must account for the specific material's springback and forming limits.</p></section>

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —