Coining Process in Automotive Stamping: Precision & Springback Control

TL;DR

The coining process in automotive stamping is a high-precision cold-forming technique where sheet metal is compressed between a punch and die with a clearance significantly less than the material thickness. Unlike standard air bending, coining forces the metal to flow plastically, effectively eliminating internal stresses and reducing springback to near-zero levels. This process requires immense tonnage—typically 5 to 8 times that of standard forming—to create structurally rigid, tight-tolerance features like chamfers, stiffeners, and calibrated angles.

What is Coining in Automotive Stamping?

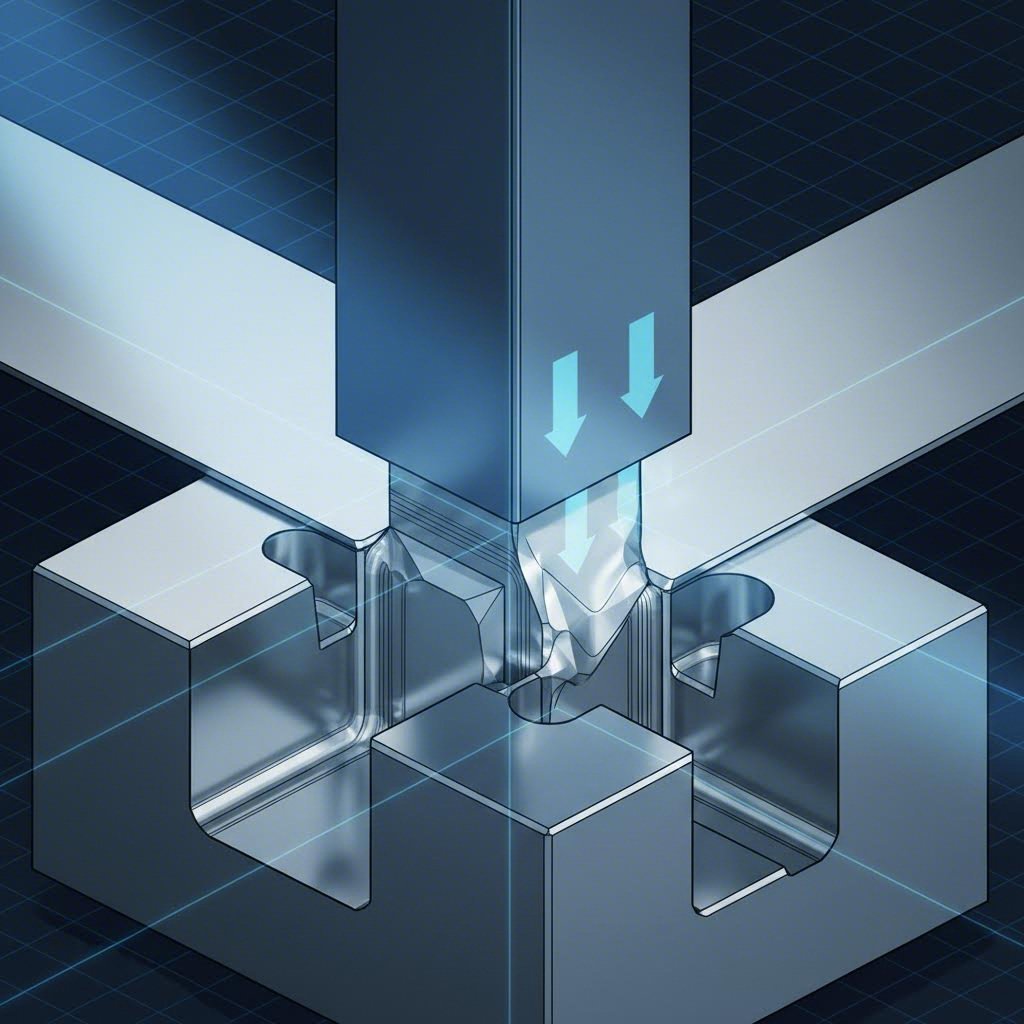

At its core, coining is defined by a distinct mechanical condition: the clearance between the punch and the die is less than the thickness of the sheet metal being formed. While standard stamping operations fold or stretch the metal, coining aggressively compresses it. This compressive force is sufficient to exceed the material's yield strength, inducing plastic flow that forces the metal to conform perfectly to the die cavity, much like a liquid.

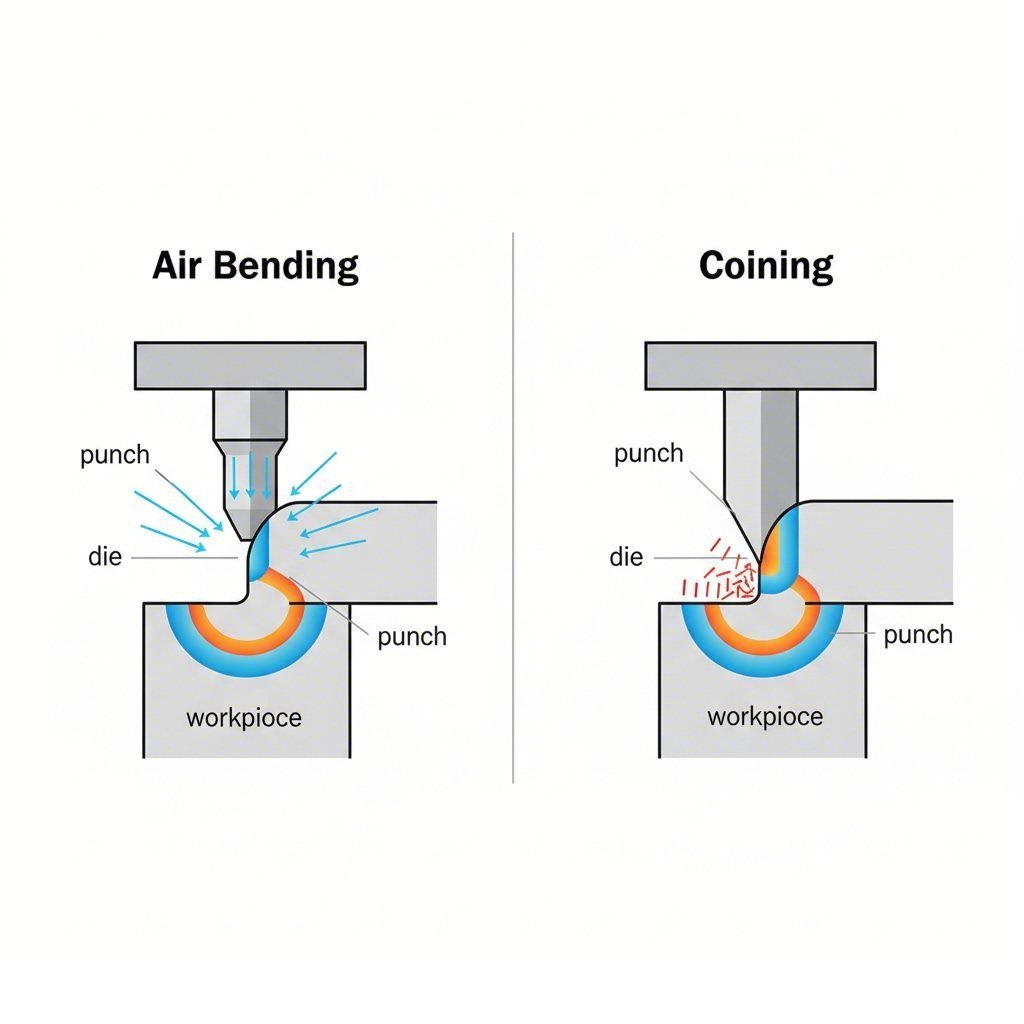

This mechanism distinguishes coining from other forming methods. In "air bending," the punch pushes the metal into a V-die without bottoming out, leaving the final angle dependent on elastic recovery. In coining, the punch tip penetrates the metal past the neutral axis, thinning the material at the point of contact. This action works to harden the surface and refine the grain structure, resulting in a part that is not only dimensionally precise but often structurally superior in the coined region.

The term "closed die" is often used to describe this environment. Because the metal is trapped and pressurized, it cannot escape, forcing it to fill every detail of the tooling. This is why coining is the preferred method for creating intricate features on automotive components that require absolute repeatability, such as electrical contacts and precision sensor brackets.

The "Killer App": Springback Reduction & Precision

The single most critical application of the coining process in automotive stamping is the management of springback. High-strength steels used in modern vehicle chassis are notorious for springing back toward their original shape after the forming load is removed, causing significant assembly issues.

Coining solves this by "calibrating" the bend. When the punch compresses the radius of a bent part (such as a flange), it relieves the tensile and compressive stresses that naturally build up during the bending phase. By neutralizing these internal forces, the metal loses its "memory" of the flat shape and locks into the coined angle.

Industry data highlights the effectiveness of this approach. For complex automotive flanges, springback can cause deviations of up to 3mm, which is unacceptable for robotic welding assembly. Applying a coining operation to the bend radius can bring these deviations down to within ±0.5mm tolerances. This precision makes coining indispensable for manufacturing safety-critical parts where geometric accuracy is non-negotiable.

Coining vs. Embossing vs. Bottoming

Confusion often arises between coining, embossing, and bottoming, but they are distinct processes with different engineering requirements. The table below outlines the key differences for automotive engineers:

| Feature | Coining | Embossing | Bottoming (Bottom Bending) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material Thickness | Thins the material intentionally | Stretches material (maintains or thins slightly) | Thickness remains largely constant |

| Tonnage Requirement | Extremely High (5-8x standard) | Low to Moderate | Moderate (2-3x air bending) |

| Clearance | < Material Thickness | ~ Material Thickness + Gap | = Material Thickness |

| Primary Purpose | Precision, Structural, Springback Kill | Decorative, Stiffening, ID Marks | Angle Consistency |

| Springback | Near Zero | Moderate | Low |

While embossing creates raised or recessed features primarily for stiffness (like on heat shields) or identification, it does not alter the material's internal structure as drastically as coining. Bottoming is a middle ground, pressing the sheet against the die to set an angle, but without the extreme compressive flow that defines true coining.

Process Parameters & Tooling Requirements

Implementing coining requires robust equipment capable of delivering massive force. The tonnage formula for coining is aggressive: engineers often calculate the required force as 5 to 8 times the tonnage required for air bending. This places immense stress on the press and tooling. A 600-ton press might be necessary for coining relatively small areas on thick automotive structural steel.

Tooling Design & Hydrostatic Lock

Tooling for coining must be manufactured from high-grade hardened tool steel to resist cracking under compressive load. A critical design consideration is lubrication. Because coining is a closed-die process, applying too much lubricant can lead to hydrostatic lock. Since fluids are incompressible, trapped oil can prevent the die from closing fully or even shatter the tooling under pressure. Controlled, minimal lubrication is essential.

The Importance of Press Rigidity

The press itself must be exceptionally rigid. Any deflection in the press bed or ram will result in uneven coining, leading to inconsistent part thickness. For manufacturers moving from prototyping to mass production, validating press capacity is a crucial step. Companies like Shaoyi Metal Technology bridge this gap by offering precision stamping services with press capabilities up to 600 tons, ensuring that even high-tonnage coining operations are executed with IATF 16949-certified accuracy for critical components like control arms and subframes.

Common Automotive Applications

Beyond simple "coins" or medallions, the coining process is integral to the functionality of many vehicle systems. Common applications include:

- Structural Brackets: Coining the bend radii of thick mounting brackets ensures the angles remain perfectly 90 degrees, allowing for seamless bolt alignment during assembly.

- Electrical Contacts: In EV battery systems and sensors, coining creates perfectly flat, work-hardened contact surfaces that improve conductivity and wear resistance.

- Precision Washers: Coining is used to create chamfered edges on washers and spacers, removing sharp burrs and creating a lead-in for fasteners.

- Burr Flattening: After a blanking operation, edges can be coined to flatten the fracture zone, making the part safe to handle without a secondary tumbling process.

Precision is the Standard

Coining remains the gold standard for achieving high-tolerance geometries in automotive stamping. While it demands higher tonnage and more expensive tooling than simple forming, the payoff in eliminated springback and assembly-ready precision is unmatched. For engineers designing the next generation of chassis and safety components, mastering the coining process is not just an option—it is a necessity for meeting modern quality standards.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the main difference between coining and embossing?

The primary difference lies in material flow and thickness. Coining compresses the metal to reduce its thickness and induce plastic flow for high precision, whereas embossing stretches the metal to create raised or recessed designs without significantly altering the material's bulk density or internal structure.

2. How much tonnage is required for coining?

Coining is extremely force-intensive, typically requiring 5 to 8 times the tonnage needed for standard air bending. The exact force depends on the material's tensile strength and the surface area being coined, but it is common for the pressure to exceed the material's yield strength significantly to ensure permanent deformation.

3. Does coining eliminate springback?

Yes, coining is one of the most effective methods for eliminating springback. By compressing the material past its yield point, coining relieves residual internal stresses that cause metal to return to its original shape. This allows for the production of parts with extremely tight angular tolerances, often within ±0.25 degrees.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —