Cleaning Stamped Metal Parts: Process Guide & Method Comparison

TL;DR

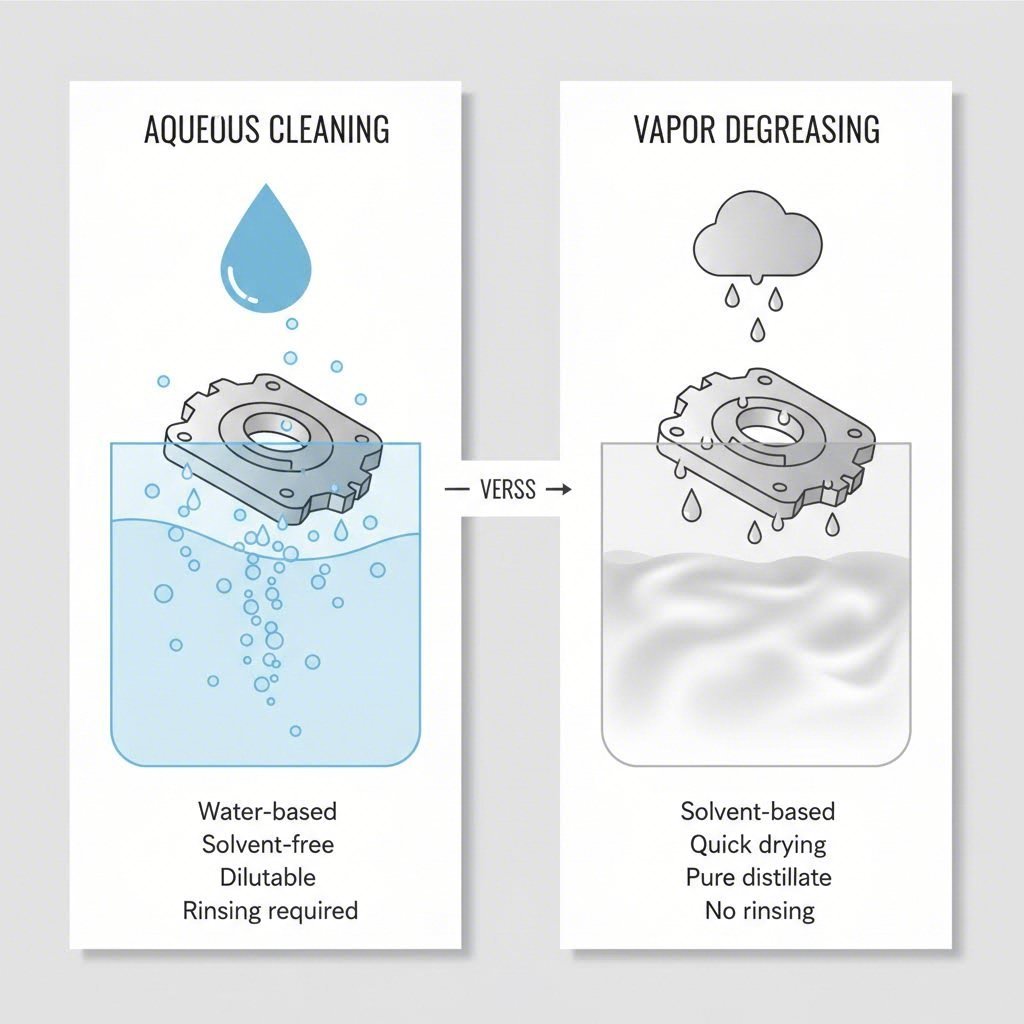

Cleaning stamped metal parts is a critical manufacturing step that bridges the gap between raw fabrication and finishing operations like plating, welding, or painting. The process generally relies on one of three primary methods: Aqueous Cleaning (using water and detergents for polar soils), Vapor Degreasing (using solvents for heavy oils and complex geometries), or Ultrasonic Cleaning (using cavitation for precision needs). Success depends on the "Clean-Rinse-Dry" cycle: removing the specific contaminant, preventing re-deposition through proper rinsing, and ensuring complete dryness to prevent flash rust or spotting.

The choice of method is dictated by the soil type (petroleum-based vs. water-soluble), the part's geometry (blind holes vs. flat surfaces), and downstream requirements. Failure to clean parts effectively leads to costly defects, including weld porosity, adhesion failure, and assembly rejections.

The High Cost of Dirty Parts: Downstream Impact

In precision manufacturing, "visually clean" is rarely clean enough. Stamped parts leave the press covered in drawing lubricants, metal fines, oxides, and shop dust. If these contaminants remain on the surface, they act as barrier layers that compromise every subsequent operation. For process engineers, the cost of inadequate cleaning is measured in scrap rates and warranty claims.

The impact of residual soil is specific and severe:

- Welding Failures: Oil residues vaporize during welding, causing porosity and weak joints. Metal fines can create inclusions that compromise structural integrity.

- Plating and Coating Delamination: For processes like e-coating, powder coating, or electroplating, the surface must be chemically active. Residual surfactants or oils prevent adhesion, leading to peeling, blistering, or "fish-eye" defects.

- Assembly Issues: In automated assembly, particulate contamination can cause friction or jamming in tight-tolerance mechanisms.

High-stakes industries enforce strict cleanliness standards. For instance, automotive stamping specialists like Shaoyi Metal Technology integrate rigorous quality controls from rapid prototyping through mass production to ensure components meet global OEM standards (such as IATF 16949) before they ever reach the assembly line. This holistic approach highlights that cleaning is not just a final wash—it is a quality gate.

Identifying Contaminants & Substrates

Effective cleaning starts with the principle of "Like Dissolves Like." Engineers must classify the soil to select the correct chemistry. A mismatch—such as using a water-based cleaner on heavy petroleum grease without the right emulsifiers—will result in parts that are merely wet, not clean.

Contaminant Classification

Polar Contaminants (Inorganic): These include salts, metal oxides, laser scale, and water-soluble coolants. They are best removed by aqueous systems because water is a polar solvent that naturally dissolves salts and, with the help of detergents, lifts inorganic soils.

Non-Polar Contaminants (Organic): These include petroleum-based stamping oils, waxes, grease, and rust inhibitors. These hydrophobic soils repel water. They are most effectively removed by solvent cleaning (vapor degreasing) or aqueous systems heavily fortified with specific surfactants and emulsifiers.

Substrate Sensitivity

The metal itself dictates the pH and aggressiveness of the cleaner. Stainless steel and mild steel are generally robust, tolerating high-temperature alkaline washes. However, soft metals like aluminum, zinc, and magnesium are reactive. High-pH alkaline cleaners can etch aluminum, turning it black or compromising its dimensions. For these materials, neutral pH cleaners or inhibited alkaline solutions are mandatory.

Method 1: Aqueous Cleaning Systems

Aqueous cleaning is the most common method for general industrial washing. It relies on a combination of Time, Temperature, Mechanical Action, and Chemistry (TACT) to remove soils. The process typically involves immersion or spray washing with water-based detergents followed by rinsing and drying.

How It Works

In an aqueous system, detergents lower the surface tension of water, allowing it to wet the part. Surfactants emulsify oils, trapping them in micelles so they can be rinsed away. Mechanical action—provided by spray nozzles, agitation, or rotation—physically dislodges particulates like metal fines and shop dust.

Pros and Cons

- Pros: Excellent for removing polar soils and particulates; environmentally compliant (no hazardous air pollutants); generally lower chemical costs.

- Cons: High energy consumption (heating water and drying parts); risk of flash rust if not dried immediately; difficulty cleaning blind holes where water gets trapped; wastewater treatment requirements.

Aqueous systems are ideal for flat parts, high-volume runs, and water-soluble contaminants. However, the "drying challenge" is significant: complex stamped parts with hems or crevices may trap water, leading to corrosion before the part reaches the next station.

Method 2: Vapor Degreasing (Solvent Cleaning)

Vapor degreasing is the preferred method for parts with complex geometries, blind holes, or heavy petroleum-based oils. It uses a solvent (often a fluorinated fluid or modified alcohol) instead of water. The process occurs in a closed-loop system where solvent is boiled, creates a vapor, condenses on the cool parts, and drips off, carrying soils with it.

The Condensation Cycle

When cool metal parts enter the vapor zone, the hot solvent vapor instantly condenses on the surface. This pure, distilled solvent dissolves oils and greases on contact. Because the solvent has a low surface tension (often < 20 dynes/cm vs. water's 72 dynes/cm), it penetrates deep into tight crevices, threaded holes, and spot-welded seams where water cannot reach.

Vacuum Degreasing

Advanced systems use vacuum technology to remove air from blind holes, forcing solvent into every void. This ensures 100% surface contact even in the most intricate stamped designs. Vacuum drying subsequently boils off the solvent at low temperatures, leaving parts completely dry.

Pros and Cons

- Pros: Superior cleaning of complex geometries; instant drying (no rust risk); small footprint; "one-step" clean/rinse/dry; effective on heavy oils and waxes.

- Cons: Higher initial equipment cost; chemical handling regulations (though modern solvents are much safer than legacy nPB or TCE).

Method 3: Ultrasonic & Immersion Cleaning

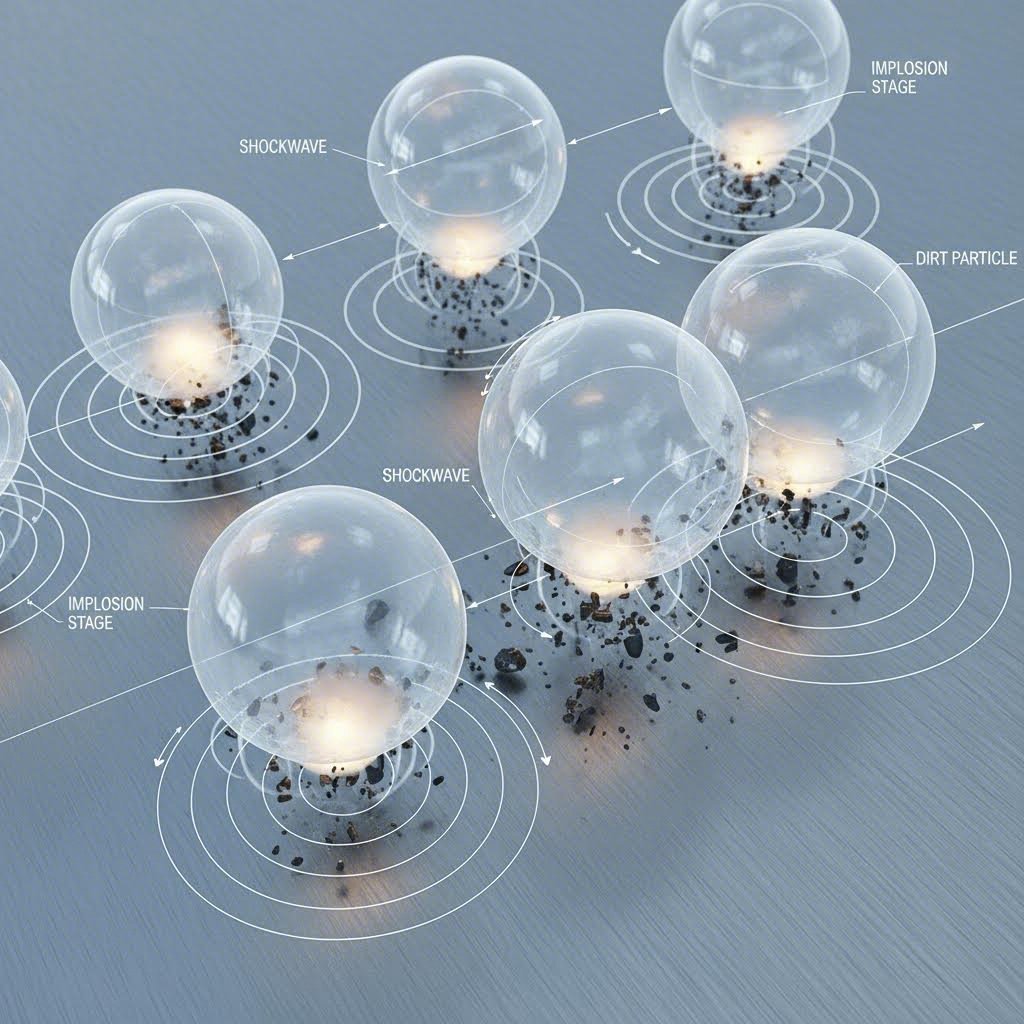

When parts require precision cleaning to remove microscopic particles or tenacious films, ultrasonic cleaning is added to either aqueous or solvent-based systems. This method uses high-frequency sound waves to create cavitation bubbles in the liquid.

The Power of Cavitation

Transducers generate sound waves (typically 25 kHz to 80 kHz) that create millions of microscopic vacuum bubbles. When these bubbles implode against the metal surface, they generate intense localized energy (temperatures up to 10,000°F and pressures up to 5,000 psi at the microscopic level). This scrubbing action blasts contaminants out of surface irregularities, blind holes, and internal threads.

Frequency Selection:

- 25 kHz: Large bubbles, aggressive cleaning. Best for heavy distinct parts like engine blocks.

- 40 kHz: The industry standard. Balanced cleaning for general stamped parts.

- 80+ kHz: Fine bubbles, gentle cleaning. Best for delicate electronics, soft metals, or removing sub-micron particles.

Process Control: Rinsing, Drying, & Validation

The cleaning agent lifts the soil, but the rinse removes it. A common failure mode in stamping is "drag-out," where contaminated cleaner dries on the part, leaving a residue. A cascade rinse system (using successively cleaner water tanks) is standard practice to prevent this.

The Drying Criticality

Drying is not passive; it is an active process control. For aqueous systems, air knives shear water off flat surfaces, while vacuum dryers are necessary for complex shapes to boil water out of crevices. Incomplete drying leads to staining and corrosion. Vapor degreasing systems inherently solve this by using volatile solvents that evaporate rapidly without leaving residue.

Validation Methods

How do you know it's clean? Validation depends on the required cleanliness level:

- Water Break Test: A simple shop-floor test. If a continuous sheet of water clings to the part (sheets), it is clean. If the water beads up, oils remain.

- Dyne Pens: Markers with specific surface tension fluids. If the ink stays wet, the surface energy is high (clean). If it reticulates (beads), the surface is below that energy level (dirty).

- White Glove / Wipe Test: Visual inspection for gross particulates.

By matching the cleaning method to the soil and substrate, and rigorously controlling the rinse and dry cycles, manufacturers ensure that their stamped metal parts are truly ready for the demands of the real world.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —