Automotive Fender Stamping Process: Engineering Class A Precision

TL;DR

The automotive fender stamping process is a high-precision manufacturing sequence that transforms flat metal coils into complex, aerodynamic "Class A" exterior panels. This process typically utilizes a tandem or transfer press line with forces exceeding 1,600 tons to execute four critical die operations: drawing, trimming, flanging, and piercing. Success depends on rigorous control of material flow, die surface finish, and elastic recovery (springback) to ensure the final component meets the flawless aesthetic standards required for vehicle assembly.

Phase 1: Material Preparation & Blanking

Before entering the main press line, the raw material—typically Cold Rolled Steel (CRS) or high-strength Aluminum alloy—must be prepared with exacting cleanliness. For exterior panels like fenders, surface quality begins at the coil level. Aluminum is increasingly preferred for modern EVs to reduce weight, though it presents higher challenges with springback compared to traditional steel.

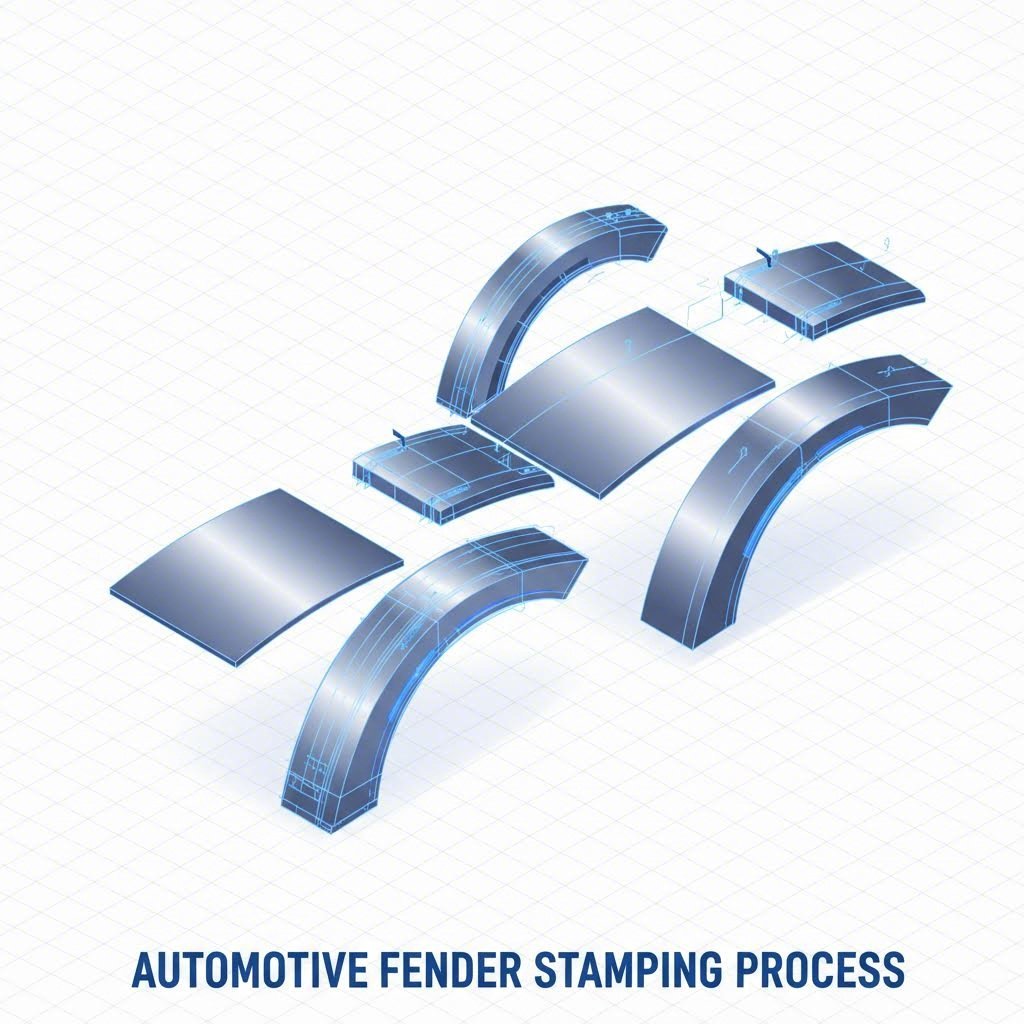

The process starts with Blanking, where the continuous coil is unrolled, washed, and cut into shaped flat sheets called "blanks." Unlike internal structural parts, fender blanks require a trapezoidal or contoured profile that roughly mimics the final part's footprint. This optimization minimizes scrap material during the subsequent trimming phase.

Washing and Lubrication are critical here. The blank passes through a washer to remove any rolling mill oil or debris. Even a microscopic particle of dust trapped between the blank and the die during the next phase can create a "pimple" or surface defect, rendering the part scrap. A precise film of forming lubricant is then applied to facilitate the deep drawing process.

Phase 2: The Press Line (Draw, Trim, Flange, Pierce)

The heart of the automotive fender stamping process occurs on a transfer or tandem press line, typically consisting of four to six distinct die stations. Each station performs a specific operation to shape the metal incrementally.

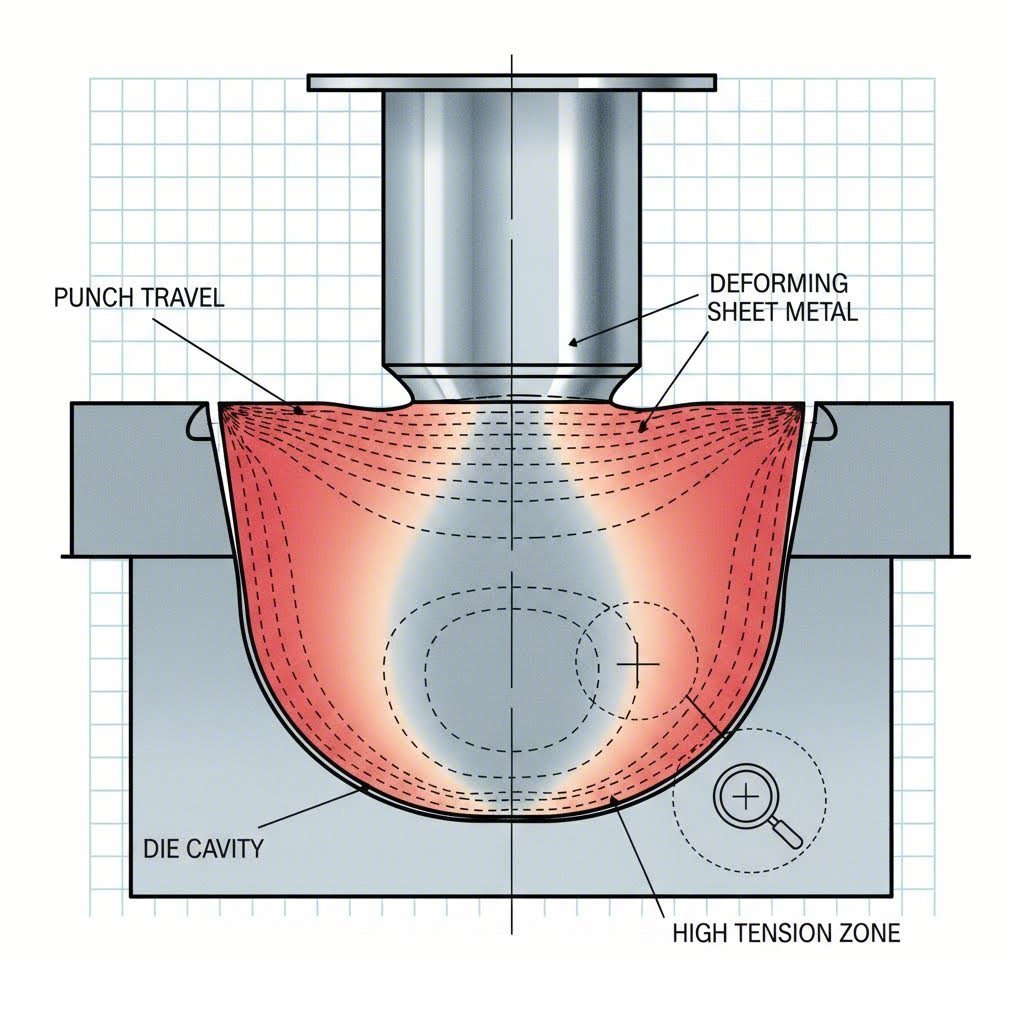

Op 10: Deep Drawing

The first and most violent impact happens in the Draw Die. A press exerting 1,000 to 2,500 tons of force pushes a punch into the metal blank, forcing it into a cavity. This creates the primary 3D geometry of the fender, including the wheel arch and headlight contours. The metal flows plastically, stretching by up to 30-40%. Binder rings hold the edges of the sheet to control the flow rate; if the metal flows too fast, it wrinkles; too slow, and it splits.

Op 20: Trimming & Scrap Removal

Once the shape is set, the part moves to the Trim Die. Here, high-precision shearing blades cut away the excess metal (binder scrap) used to hold the part during drawing. This operation defines the fender's true perimeter and wheel well opening. The scrap metal falls down chutes to be recycled, while the part moves forward.

Op 30: Flanging & Restriking

Fenders need 90-degree edges (flanges) to mount to the vehicle's unibody and to create safe, hemmed edges for the wheel well. The Flange Die bends these edges down. Simultaneously, a "restrike" operation may occur, where the die hits specific areas of the panel again to calibrate the surface and lock in the geometry, reducing springback.

Op 40: Piercing & Cam Operations

The final mechanical stage involves piercing mounting holes, antenna cutouts, or side-marker light openings. Cam dies—mechanism-driven tools that convert vertical press motion into horizontal cutting action—are often used here to punch holes on the vertical surfaces of the fender without deforming the main panel.

Phase 3: Class A Surface Engineering

Unlike floor pans or structural pillars, a fender is a Class A surface. This means it must be aesthetically perfect, with G2 or G3 curvature continuity that reflects light without distortion. Achieving this requires engineering that goes beyond simple metal forming.

Die surfaces for fenders are polished to a mirror finish. During the design phase, engineers use simulation software to predict "skid lines"—marks caused by the material dragging across the tool. To counteract this, the stamping process often employs "over-crowning" compensation, bending the panel slightly past its intended shape so that when it springs back, it settles into the perfect nominal dimension.

Manufacturers must also bridge the gap between rapid prototyping and high-volume consistency. For companies scaling production, partners like Shaoyi Metal Technology utilize IATF 16949-certified precision stamping solutions to deliver critical automotive components, ensuring that rigorous global OEM standards are met from the initial tooling design to the final stamped output.

Phase 4: Common Defects & Quality Control

Stamping large, complex panels introduces specific defect risks that must be managed continuously. Quality control is not just a final step but an integrated part of the line.

- Splits and Cracks: Occur when the material thins excessively during the Deep Draw (Op 10), usually due to insufficient lubrication or excessive binder pressure.

- Wrinkles: Caused by loose material flow where the metal bunches up rather than stretching. This is catastrophic for Class A surfaces.

- Springback: The tendency of metal (especially aluminum) to return to its original shape after the press opens. This creates dimensional inaccuracies that create gaps during vehicle assembly.

- Surface Lows/Highs: Subtle depressions or bumps invisible to the naked eye but glaring once painted.

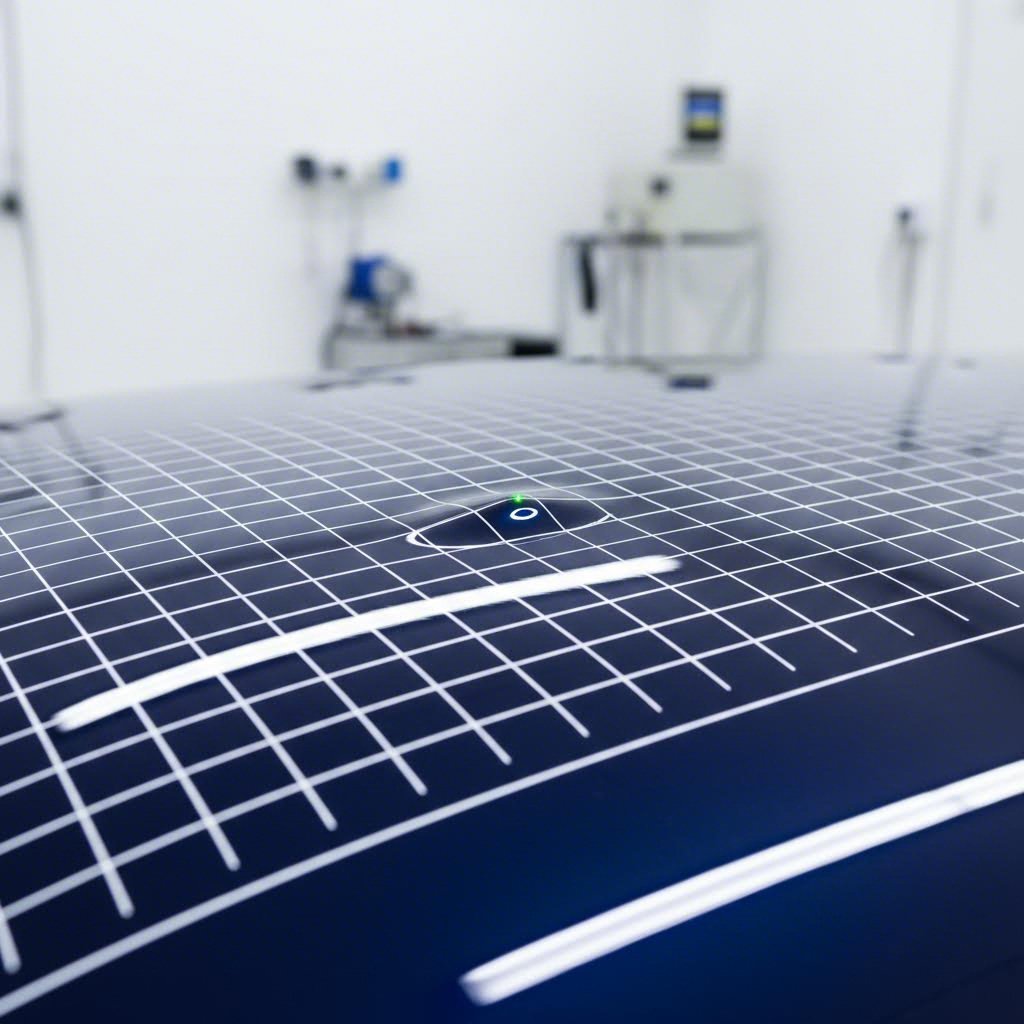

The Highlight Room

To detect these surface flaws, fenders pass through a "Highlight Room" or "Green Room." Inspectors apply a thin film of oil to the panel and view it under high-intensity light grids. The oil creates a reflective surface, causing the grid lines to warp visually if there is even a micron-level depression or ding in the metal. Automated optical inspection systems are also increasingly used to map the surface topology against the CAD model.

Phase 5: Assembly & Finishing

Once the stamping is verified, the fender moves to post-processing. While fenders are primarily single-piece stampings, they often require the attachment of small reinforcement brackets or nuts for mounting.

Hemming and Racking

If the fender is a dual-layer design (rare for front fenders, common for doors/hoods), it would undergo hemming. For standard fenders, the focus is on safe racking. Finished panels are placed into specialized racks with non-abrasive dunnage. These racks prevent the panels from touching each other, preserving the Class A surface during transport to the Body Shop for welding and painting.

Mastering the Curve

The production of an automotive fender is a balance of brute force and microscopic precision. From the initial 1,600-ton draw to the final light-grid inspection, every step is calculated to maintain the integrity of the metal's surface. As automakers shift toward lighter aluminum alloys and more complex aerodynamic designs, the stamping process continues to evolve, demanding tighter tolerances and more advanced die engineering to deliver the flawless curves seen on the showroom floor.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the main steps in the fender stamping process?

The core process typically follows four main stages: Blanking (cutting the raw coil), Drawing (forming the 3D shape), Trimming (cutting away excess metal), and Flanging/Piercing (creating edges and mounting holes). Some lines may include a Restrike operation for final surface calibration.

2. Why is the drawing stage critical for fenders?

The drawing stage is where the flat metal is stretched into its three-dimensional form. It is the most critical step because it establishes the panel's geometry and surface tension. Improper drawing can lead to splits, wrinkles, or "soft" areas that dent easily, ruining the part's Class A quality.

3. Do you need a special hammer for metal stamping?

No, industrial automotive stamping does not use hammers. It relies on massive hydraulic or mechanical presses and precision-machined dies. While manual metal shaping might use hammers and dollies for restoration or custom work, mass production is an automated, high-tonnage process.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —