Automotive Chassis Stamping Process: The Technical Guide

TL;DR

The automotive chassis stamping process is a high-precision manufacturing method essential for producing the structural backbone of modern vehicles. It involves deforming heavy-gauge sheet metal—typically High-Strength Steel (HSS) or aluminum—into complex geometries using massive hydraulic or mechanical presses, often exceeding 1,600 tons of force. The workflow moves from blanking and piercing to deep drawing and final trimming, requiring strict adherence to tolerances as tight as ±0.01 mm to ensure crash safety and structural rigidity. For engineers and procurement managers, understanding the trade-offs between hot and cold stamping, as well as choosing the right die technology, is critical for balancing cost, weight, and performance.

Fundamentals: Chassis vs. Body Stamping

While both chassis and body panels utilize metal stamping, their engineering requirements diverge significantly. Body stamping focuses on "Class A" surface aesthetics—creating flawless, aerodynamic curves for fenders and doors where visual perfection is paramount. In contrast, chassis stamping prioritizes structural integrity and durability. Chassis components, such as frame rails, cross-members, and suspension control arms, must withstand immense dynamic loads and crash forces without failure.

This functional difference dictates the material selection and processing parameters. Chassis parts are typically stamped from thicker gauges of High-Strength Steel (HSS) or Advanced High-Strength Steel (AHSS), which offer superior tensile strength but are more difficult to form due to reduced ductility. According to Neway Precision, producing these large, deep-drawn components often requires specialized deep drawing techniques where the depth of the part exceeds its diameter, a process distinct from standard shallow stamping.

The equipment used reflects these demands. While body panels might be formed on high-speed transfer lines, chassis components often require higher tonnage presses—sometimes hydraulic or servo-driven—to manage the work-hardening characteristics of HSS. The goal is to achieve geometric complexity while maintaining uniform material thickness, ensuring the vehicle's frame meets rigorous safety standards.

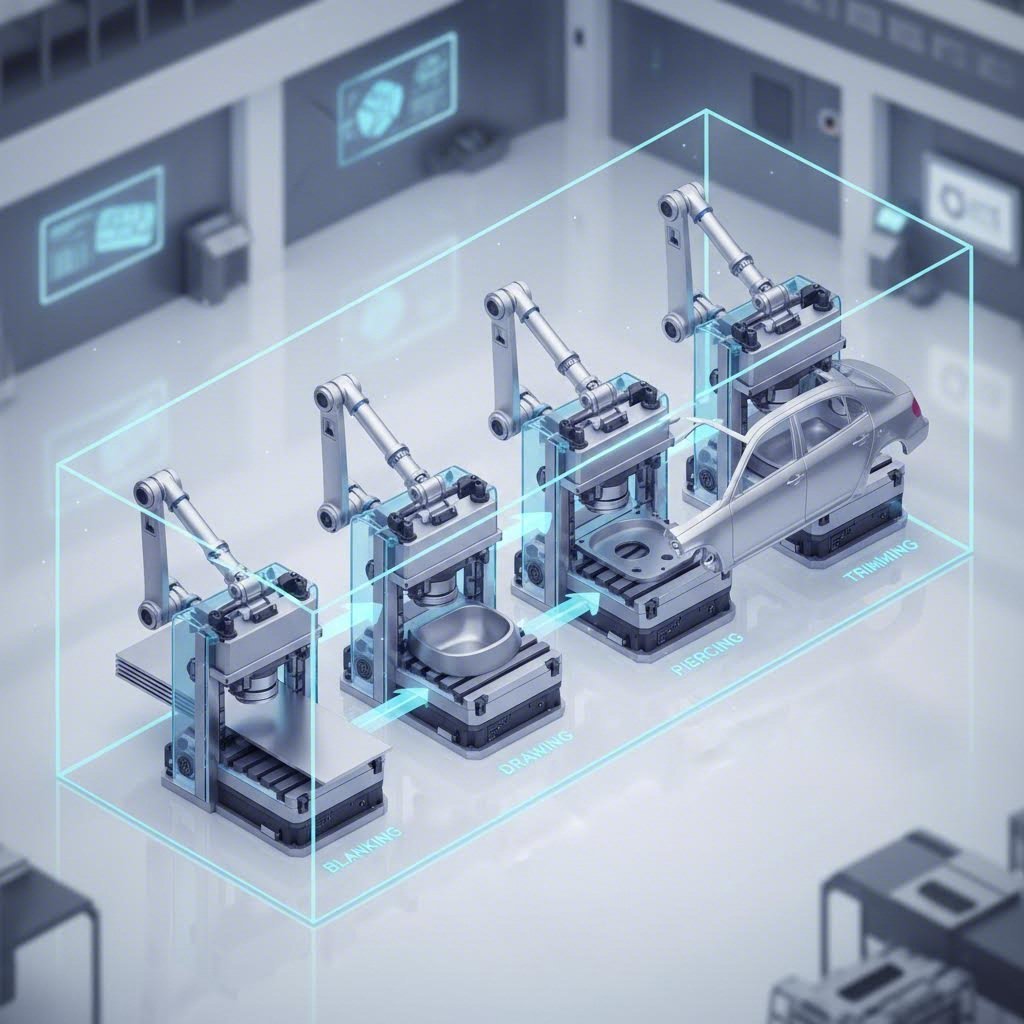

The Stamping Workflow: Step-by-Step

The transformation from a flat metal coil to a finished chassis component follows a rigorous sequential workflow. Based on production patterns observed at major manufacturers like Toyota, the process can be broken down into four primary stages, each critical for dimensional accuracy:

- Blanking and Preparation: The process begins with unwinding the metal coil. The material is leveled to remove internal stresses and then cut into rough "blanks"—flat shapes that approximate the final part's footprint. This stage determines material utilization; efficient nesting of blanks minimizes scrap waste.

- Forming and Deep Drawing: The blank is fed into the press, where a male punch forces it into a female die. For chassis parts, this is often a deep drawing operation that creates the 3D geometry, such as the U-channel of a frame rail. The metal flows plastically under tons of pressure, defining the component's structural profile.

- Trimming and Piercing: Once the general shape is formed, secondary dies trim away excess material (flash) and pierce necessary mounting holes or slots. Precision is vital here; mounting points for suspension or engine components must align perfectly with other sub-assemblies.

- Flanging and Coining: The final steps involve bending edges (flanging) to increase stiffness and "coining" specific areas to flatten surfaces or imprint details. This ensures the part creates a tight, vibration-free interface when welded or bolted to the vehicle frame.

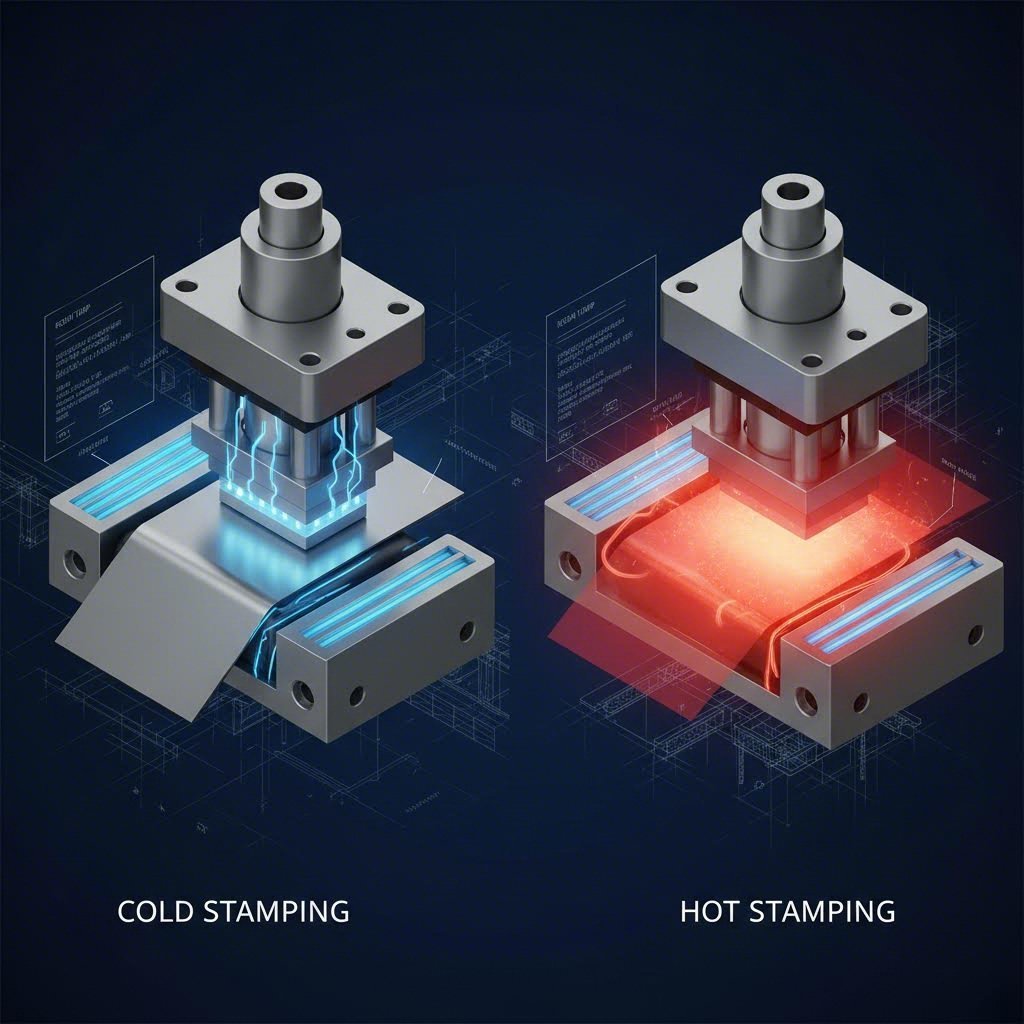

Critical Decision: Hot Stamping vs. Cold Stamping

One of the most significant technical decisions in chassis manufacturing is choosing between hot and cold stamping. This choice is largely driven by the material's strength requirements and the component's complexity.

| Feature | Cold Stamping | Hot Stamping (Press Hardening) |

|---|---|---|

| Process Temperature | Room temperature | Heated to ~900°C+, then quenched |

| Material Strength | Typically < 1,000 MPa | Up to 1,500+ MPa (Ultra-High-Strength) |

| Springback Risk | High (requires compensation) | Near zero (part "freezes" in shape) |

| Cycle Time | Fast (high volume) | Slower (requires heating/cooling) |

| Primary Use | General chassis parts, brackets | Safety-critical reinforcements (B-pillars, rockers) |

Cold stamping is the traditional method, favored for its speed and lower energy costs. It is ideal for parts made from ductile steel grades where extreme strength is not the limiting factor. However, as manufacturers push for lightweighting, they increasingly turn to Hot Stamping.

Hot stamping involves heating boron steel blanks until they become malleable, forming them in the die, and then rapidly cooling (quenching) them within the tool. This process produces parts with exceptional strength-to-weight ratios, essential for modern safety cages. While more expensive due to energy consumption and cycle times, it eliminates the issue of "springback," ensuring precise geometric tolerances for high-tensile parts.

Die Selection: Progressive vs. Transfer Dies

Selecting the right tooling strategy is a balance between production volume, part size, and capital investment. Two primary die configurations dominate the automotive chassis sector:

Progressive Dies

In progressive die stamping, the metal strip is fed through a single die with multiple stations. Each stroke of the press performs a different operation (cut, bend, form) as the strip advances. This method is highly efficient for smaller chassis components like brackets and reinforcements, capable of producing hundreds of parts per minute. However, it is limited by the size of the strip and is less suitable for massive structural rails.

Transfer Dies

For large chassis parts such as cross-members and subframes, transfer dies are the standard. Here, individual blanks are mechanically moved from one die station to the next by "transfer arms" or robotic systems. According to American Industrial, this method allows for more complex forming operations on larger parts that wouldn't fit in a continuous strip. Transfer lines offer greater flexibility and material efficiency for heavy-gauge components, as blanks can be nested more effectively prior to entering the press.

Challenges and Quality Control

Chassis stamping faces unique challenges due to the high-strength materials involved. Springback—the tendency of metal to return to its original shape after forming—is a persistent issue with Cold Stamped HSS. If not calculated correctly, it leads to parts that are out of tolerance, causing assembly fit-up issues.

To mitigate this, engineers use advanced Finite Element Analysis (FEA) simulations to predict material behavior and design dies with "over-bend" compensation. Eigen Engineering notes that modern stamping also integrates technologies like electromagnetically assisted forming to control strain distribution and reduce wrinkling or thinning in complex areas.

Ensuring these precise tolerances usually requires a partner with specialized capabilities. For manufacturers bridging the gap between prototype validation and mass production, firms like Shaoyi Metal Technology offer IATF 16949-certified precision stamping. Their ability to handle press tonnages up to 600 tons allows for the production of critical control arms and subframes that meet global OEM standards, ensuring that the transition from design to high-volume manufacturing maintains strict quality continuity.

Future Trends: Lightweighting and Automation

The future of the automotive chassis stamping process is being shaped by the drive for fuel efficiency and electrification. Lightweighting is the dominant trend, pushing the industry toward thinner, stronger steels and increased use of aluminum alloys. Stamping aluminum presents its own challenges, such as a higher tendency to crack, requiring precise lubrication and force control.

Simultaneously, Smart Stamping is revolutionizing the factory floor. Servo presses, which allow programmable slide motion, are replacing traditional flywheels, offering infinite control over ram speed and dwell time. This flexibility enables the forming of difficult materials that would split under constant velocity. As highlighted by Automation Tool & Die, these advanced techniques are critical for producing NVH (Noise, Vibration, and Harshness) reduction brackets and next-generation chassis structures that are both lighter and stronger.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —