Stamping Defects in Aluminum Panels: Root Causes & Technical Solutions

TL;DR

Stamping aluminum panels presents a unique engineering challenge compared to steel, primarily due to aluminum's low Young's Modulus and narrow Forming Limit Curve (FLC). The most critical defects usually fall into three categories: springback (dimensional deviation), formability failures (cracks and wrinkles), and surface imperfections (galling and surface lows). Mastering these issues requires a shift from traditional trial-and-error to digital simulation and precise process control.

For automotive applications using alloys like 6016-T4, success depends on managing the material's elastic recovery and tendency to adhere to tool steel. This guide breaks down the physics behind these failure modes and provides technical solutions for detecting, preventing, and correcting stamping defects in aluminum panels.

The Aluminum Challenge: Physics Behind the Defects

To solve stamping defects in aluminum panels, engineers must first understand why aluminum behaves differently than mild or high-strength steel. The root cause of most defects lies in two specific material properties: Elastic Modulus and Tribology.

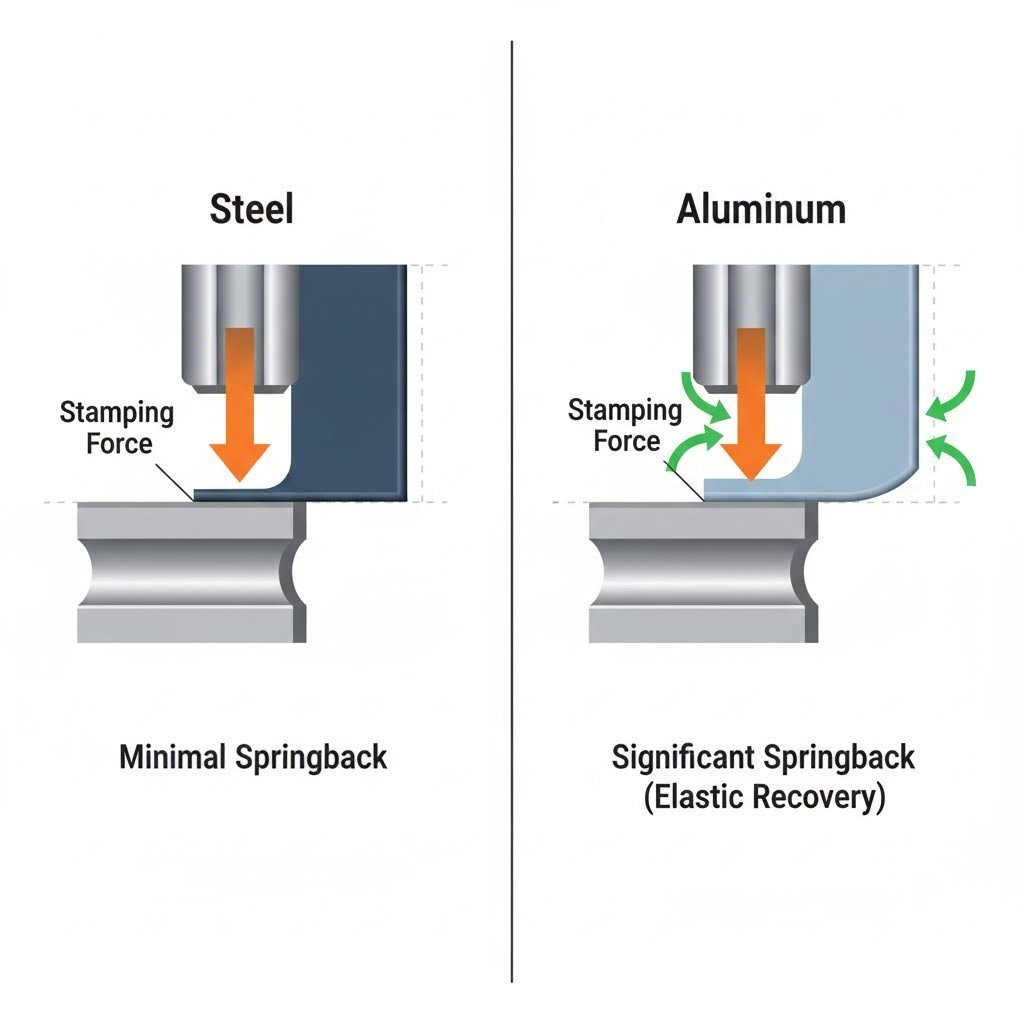

Aluminum has a Young's Modulus (elasticity) approximately one-third that of steel (approx. 70 GPa vs. 210 GPa). This means that for the same amount of stress, aluminum deforms elastically three times as much. When the forming pressure is released, the material tries to return to its original shape with much greater force, leading to severe springback. If the process does not account for this, the panel will not meet dimensional tolerances.

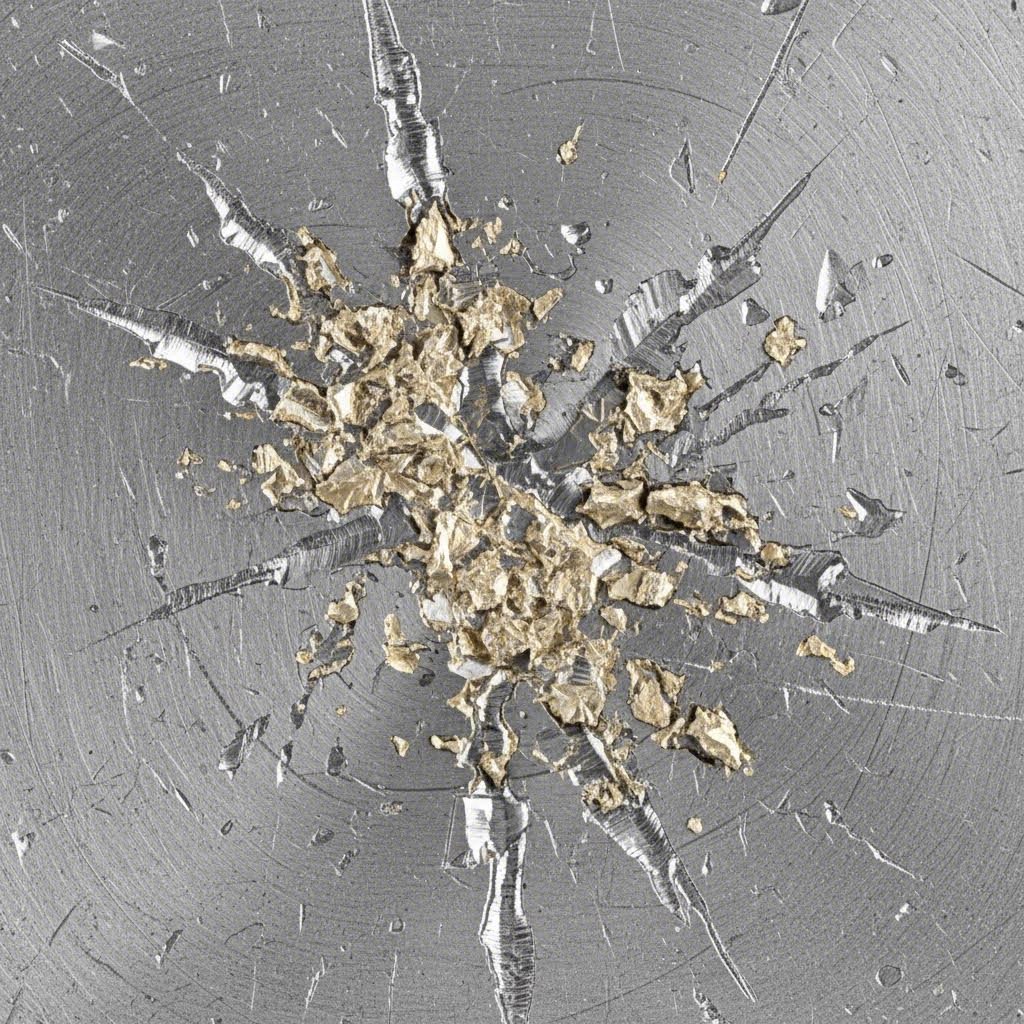

Secondly, aluminum has a high affinity for tool steel. Under the heat and pressure of stamping, the aluminum oxide layer can break down and bond to the die surface—a phenomenon known as galling. This buildup changes the friction conditions instantly, leading to inconsistent material flow, splits, and surface scratches.

Category 1: Formability Defects (Cracks, Splits & Wrinkles)

Formability defects occur when the material fails under stress, either by separating (cracking) or folding (wrinkling). These are often driven by the layout of the blank holder and the draw depth.

Cracks and Splits

Cracking is a tensile failure that happens when the material is stretched beyond its Forming Limit Curve (FLC). In aluminum panels, this often occurs at tight radii or deep draw areas where the metal cannot flow fast enough.

- Root Cause: Excessive blank holder force preventing material flow, or a draw radius that is too sharp for the alloy's thickness (commonly 0.9mm to 1.2mm for body panels).

- Solution: Reduce blank holder pressure locally or apply differential lubrication. In the design phase, increase the product radii or use simulation software (like AutoForm) to modify the addendum and allow better material feed.

Wrinkling

Wrinkling is a compressive instability. It occurs when the metal is compressed rather than stretched, causing it to buckle. This is common in the flange areas or where there is insufficient blank holder pressure.

- Root Cause: Low blank holder force or uneven die gaps. If the material is not held taut, it will fold over itself before entering the draw cavity.

- Solution: Increase blank holder force or use drawbeads to restrict material flow and generate tension. However, be careful—too much tension will flip the defect from a wrinkle to a split.

Category 2: Dimensional Defects (Springback & Twisting)

Dimensional accuracy is arguably the hardest metric to hit with aluminum panels. Unlike steel, where the part largely stays where you put it, aluminum parts "spring back" significantly.

Springback Types

Springback manifests in several ways: angular change (walls opening up), sidewall curl (curved walls), and torsional twist (the entire part twisting like a propeller). This is critical for "Class A" surfaces like hoods and doors, where even a millimeter of deviation affects the assembly gap and flushness.

Compensation Strategies

You cannot simply "iron out" springback in aluminum. The industry standard solution is geometric compensation:

- Over-bending: Designing the die to bend the metal past 90 degrees (e.g., to 93 degrees) so that it springs back to the desired 90-degree angle.

- Process Simulation: Using CAE tools to predict the elastic recovery and machining the die surface to the "compensated" shape (the inverse of the expected error).

- Restrike Operations: Adding a secondary restrike station to set critical dimensions and lock in the geometry.

Category 3: Surface & Cosmetic Defects (Class A Panels)

For automotive outer panels, surface quality is paramount. Defects here may be micro-sized but become glaringly obvious under paint.

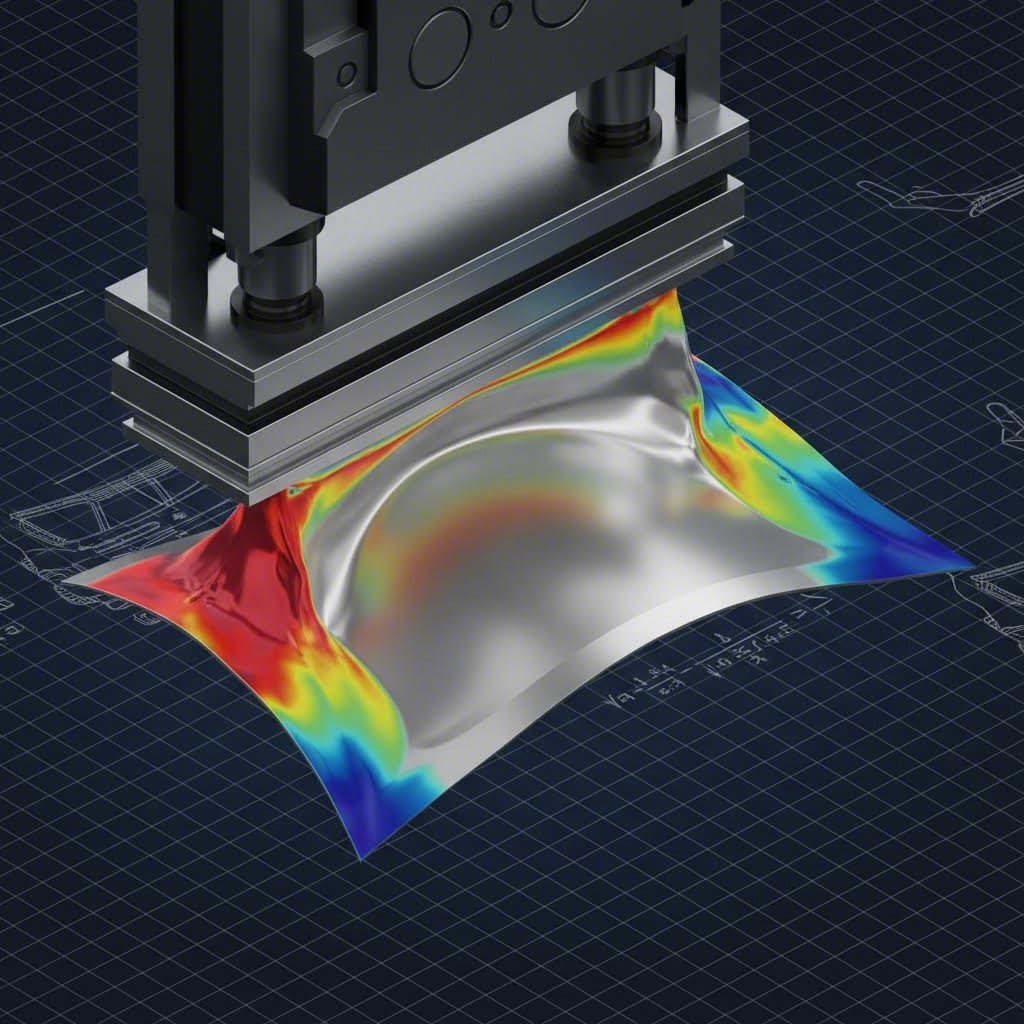

Surface Lows and Zebra Lines

Surface lows are localized depressions that disrupt the reflection of light. They often occur near door handle recesses or character lines. Quality inspectors visualize these using "Zebra Line" analysis—projecting striped light onto the panel. If the stripes distort, there is a surface low.

These defects typically result from uneven strain distribution. If the material goes slack during the stroke and then snaps tight, it creates a permanent surface distortion. The fix involves optimizing the drawbead layout to ensure positive tension is maintained on the panel skin throughout the entire stroke.

Galling (Adhesion)

Galling appears as scratches or gouges on the panel surface. It is caused by aluminum particles adhering to the die and then scoring subsequent parts. Unlike steel debris, aluminum oxide is extremely hard and abrasive.

- Prevention: Use dies coated with PVD (Physical Vapor Deposition) or DLC (Diamond-Like Carbon) to reduce friction.

- Maintenance: Implement a rigorous die cleaning schedule. Once galling starts, it compounds rapidly.

Category 4: Cutting & Edge Defects (Burrs & Slivers)

Aluminum does not break cleanly like steel; it tends to smear. This leads to unique edge defects.

Burrs

A burr is a sharp, raised edge along the trim line. While common in all stamping, aluminum burrs are often caused by improper cutting clearance. If the gap between the punch and die is too large (typically >10-12% of material thickness), the metal rolls over before cutting, creating a large burr.

Slivers and Dust

A specific nuisance in aluminum stamping is the generation of "slivers" or fine metallic dust. This dust can accumulate in the die, causing pimples or indentations on the panel surface. Managing this requires vacuum scrap removers and regular die washing.

Mastering Process Control & Sourcing

Preventing these defects requires a holistic approach that combines advanced engineering with rigorous process discipline. It starts with Virtual Tryout—simulating the entire line to predict thinning, splitting, and springback before a single block of steel is cut.

For complex manufacturing needs, partnering with an experienced fabricator is often the most efficient path to quality. Companies like Shaoyi Metal Technology bridge the gap between prototyping and mass production. With IATF 16949 certification and press capabilities up to 600 tons, they specialize in managing the tight tolerances required for precision automotive components, ensuring that issues like springback and burrs are engineered out of the process early.

Ultimately, consistent quality comes from controlling the variables: maintaining precise lubrication levels, monitoring die wear, and keeping the press line free of aluminum debris.

Conclusion

Stamping defects in aluminum panels—from the geometric frustration of springback to the cosmetic nuance of surface lows—are solvable physics problems. They are not random errors but direct consequences of the material’s low modulus and tribological properties. By leveraging simulation compensation, optimizing cutting clearances, and maintaining strict die hygiene, manufacturers can achieve the flawless "Class A" surfaces required by the modern automotive industry.

FAQ

1. What are the most common defects in aluminum stamping?

The most frequent defects are springback (dimensional inaccuracy), splitting (tearing due to low formability), wrinkling (buckling due to low compression resistance), and galling (material adhesion to the die). In cosmetic panels, surface lows and optical distortions (zebra line defects) are also critical issues.

2. How is springback different in aluminum compared to steel?

Aluminum has a Young's Modulus of roughly 70 GPa, compared to 210 GPa for steel. This means aluminum is three times more elastic. After the stamping load is removed, aluminum panels spring back significantly more than steel parts, requiring much more aggressive geometric compensation in the die design to achieve the final shape.

3. What causes surface lows in aluminum panels?

Surface lows are typically caused by uneven material flow or a sudden release of tension during the forming stroke. If the metal in the center of the panel is not held under constant tension while the edges are being drawn, it can relax and then snap back, creating a localized depression that is visible under reflective light.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —