Selecting Lubricants for Automotive Stamping: A Technical Guide

TL;DR

Selecting the optimal lubricant for automotive stamping is a critical engineering decision driven by three primary variables: the workpiece material (specifically Aluminum BIW vs. High-Strength Steel), the application method (contact rollers vs. non-contact spray), and post-process compatibility. Modern automotive production increasingly favors chlorine-free soluble oils or hot-melt technologies to handle the tribological demands of aluminum alloys while ensuring downstream weldability and environmental compliance. To prevent failures such as galling or hydraulic sticking, engineers must match fluid viscosity (<20 cSt for light forming) to press speeds and material surface topography. Ultimately, the right choice balances friction reduction with ease of cleaning and disposal.

Critical Selection Factors: Material & Process Variables

The foundation of lubricant selection lies in the interaction between the workpiece material and the stamping press. Different metals react vastly differently to friction and heat, necessitating distinct chemical formulations. For automotive applications, the sharpest divide exists between aluminum alloys and high-strength steels.

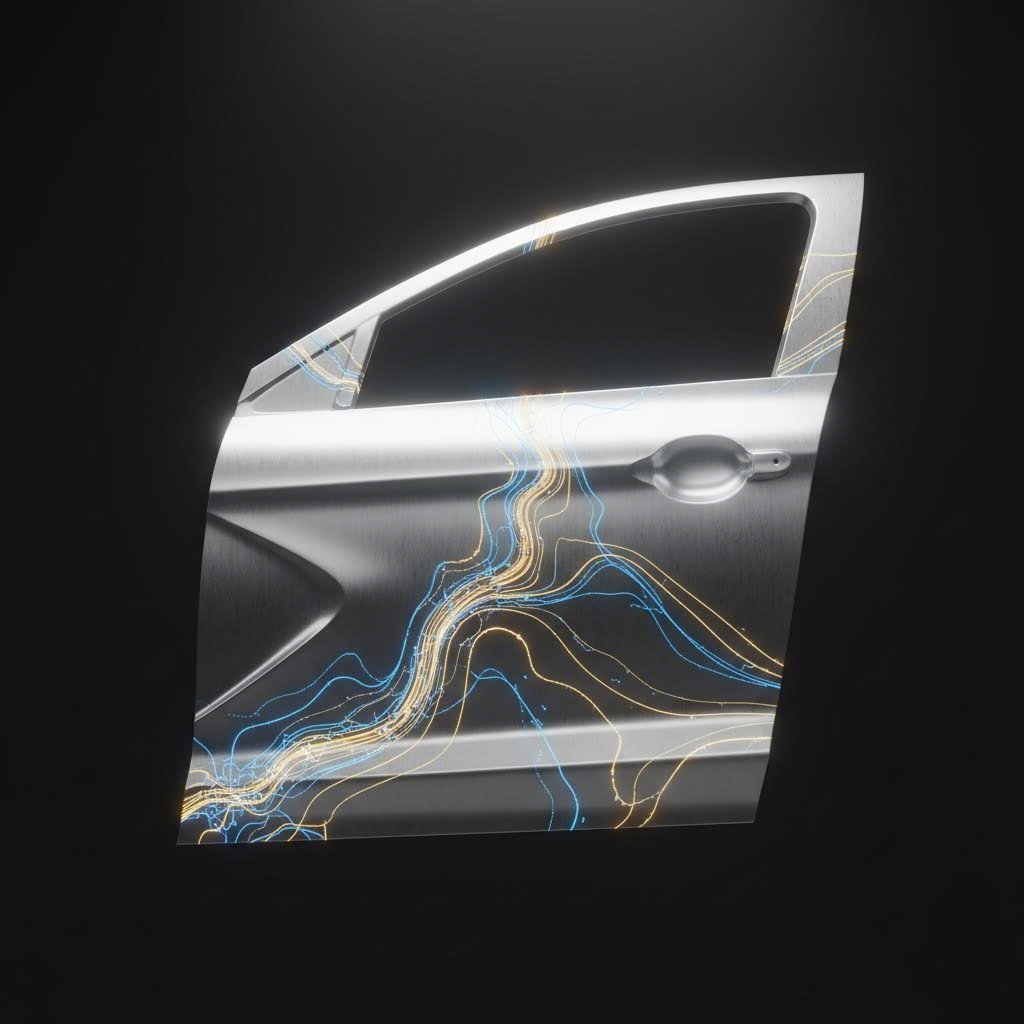

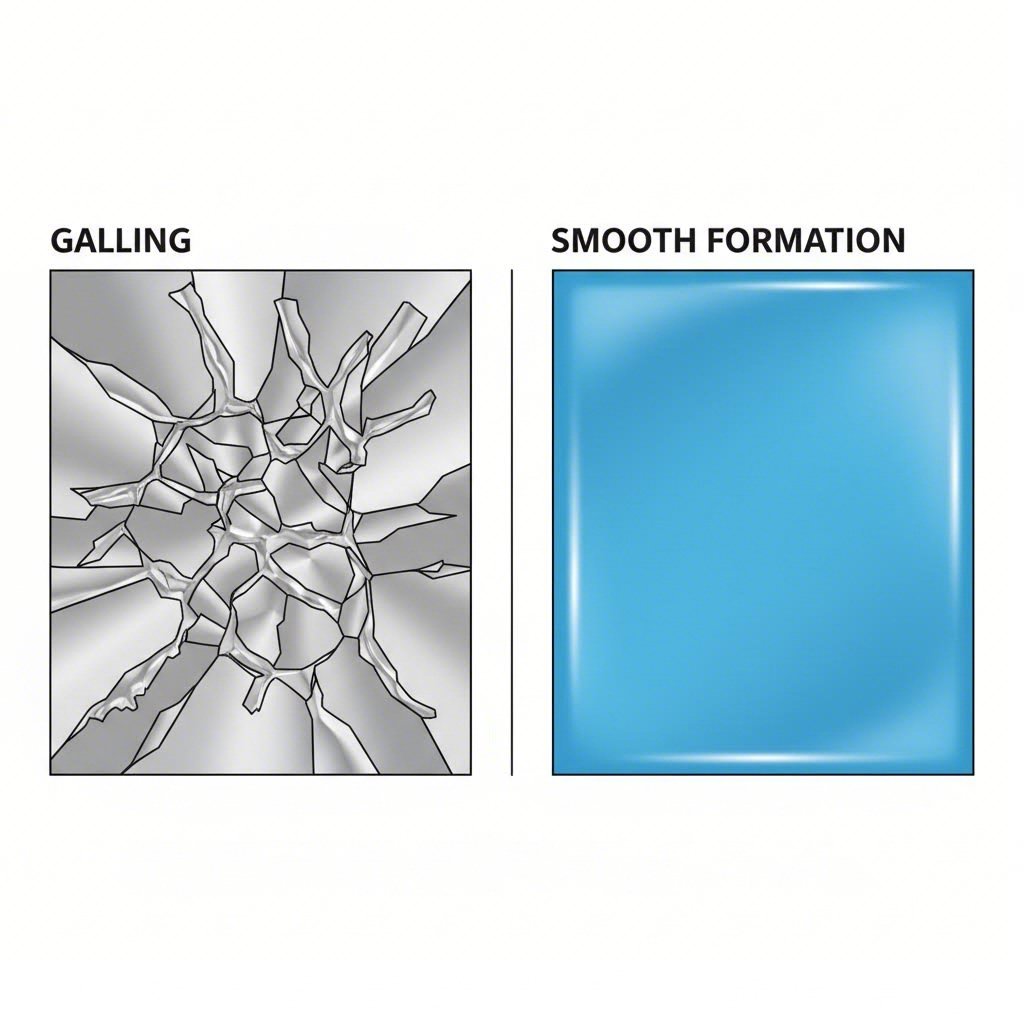

Aluminum Body-in-White (BIW) Parts typically utilize 5xxx and 6xxx series alloys, which are prone to galling—a defect where the aluminum adheres to the die surface. To combat this, lubricants requires strong boundary lubrication properties. While straight oils were historically the standard, the industry has shifted toward chlorine-free soluble oils and emulsions. These fluids provide the necessary barrier protection without the heavy residue that complicates downstream welding. Conversely, High-Strength Steels (AHSS) generate immense heat and pressure, often requiring Extreme Pressure (EP) additives (like sulfur or phosphorus) to prevent tool failure.

Viscosity is another technical specification that cannot be overlooked. A common error in high-speed stamping is selecting a lubricant that is too thick. For example, standard mill oils often have a viscosity of approximately 40 cSt at 40°C. While effective for corrosion protection during storage, this thickness can cause a "hydraulic effect" during stamping, where the fluid cannot escape the die cavity fast enough, preventing the blank from conforming to the tool geometry. For precision forming, lighter viscosity fluids (often <20 cSt) are preferred to ensure proper metal flow and prevent blanks from sticking together due to surface tension.

Production speed and volume also dictate lubricant performance. High-speed presses generate significant friction heat, requiring a fluid with excellent cooling properties—typically water-soluble coolants. For manufacturers managing complex supply chains, partnering with capable fabrication specialists is often as crucial as the chemistry itself. Companies like Shaoyi Metal Technology leverage IATF 16949-certified precision processes to handle these variables, ensuring that whether the run is for rapid prototypes or millions of OEM components, the lubricant and process parameters remain consistent.

Lubricant Types: Chemistry & Performance Comparison

Understanding the chemical categories available is essential for making an informed choice. Automotive stampers generally choose between four main categories, each with distinct trade-offs regarding lubricity, cooling, and washability.

- Straight Oils: These are neat oils with no water content. They offer superior lubricity and corrosion protection, making them ideal for heavy-duty stamping of difficult steel parts. However, they have poor cooling characteristics and leave a heavy oily residue that is difficult to clean, often requiring solvent-based degreasing.

- Water-Soluble Oils (Emulsions): These are the workhorses of the modern press room. Composed of oil dispersed in water, they offer a balanced mix of lubricity (from the oil) and cooling (from the water). They are easier to clean than straight oils and are compatible with most welding processes. New chlorine-free formulations are increasingly popular for meeting environmental regulations.

- Synthetics: These fluids contain no mineral oil and rely on chemical polymers for lubricity. They run very clean, offer excellent cooling, and are transparent, allowing operators to see the part during formation. However, they can be more expensive and may leave hard, varnish-like residues if not properly maintained.

- Dry-Film & Hot-Melt Lubricants: Essential for complex aluminum forming, particularly for deep-draw closures. Hot-melt lubricants are applied at the mill and are dry at room temperature (similar to wax), activating only when the friction heat of the press softens them. This provides exceptional boundary lubrication without the mess of liquid oils, though it requires specific pre-cleaning setups (often at elevated temperatures) to remove.

| Lubricant Type | Best Application | Key Advantage | Primary Drawback |

|---|---|---|---|

| Straight Oil | Heavy-gauge steel, severe draws | Maximum lubricity & tool life | Hard to clean; poor cooling |

| Soluble Oil | General automotive, Aluminum BIW | Balance of cooling & lubricity | Requires biological maintenance |

| Synthetic | Light gauge, coated metals | Clean running; excellent cooling | Higher cost; sticky residue |

| Hot-Melt/Dry | Complex Aluminum closures | Superior formability; no mess | Difficult to remove; requires heat |

Application Strategy: Contact vs. Non-Contact Systems

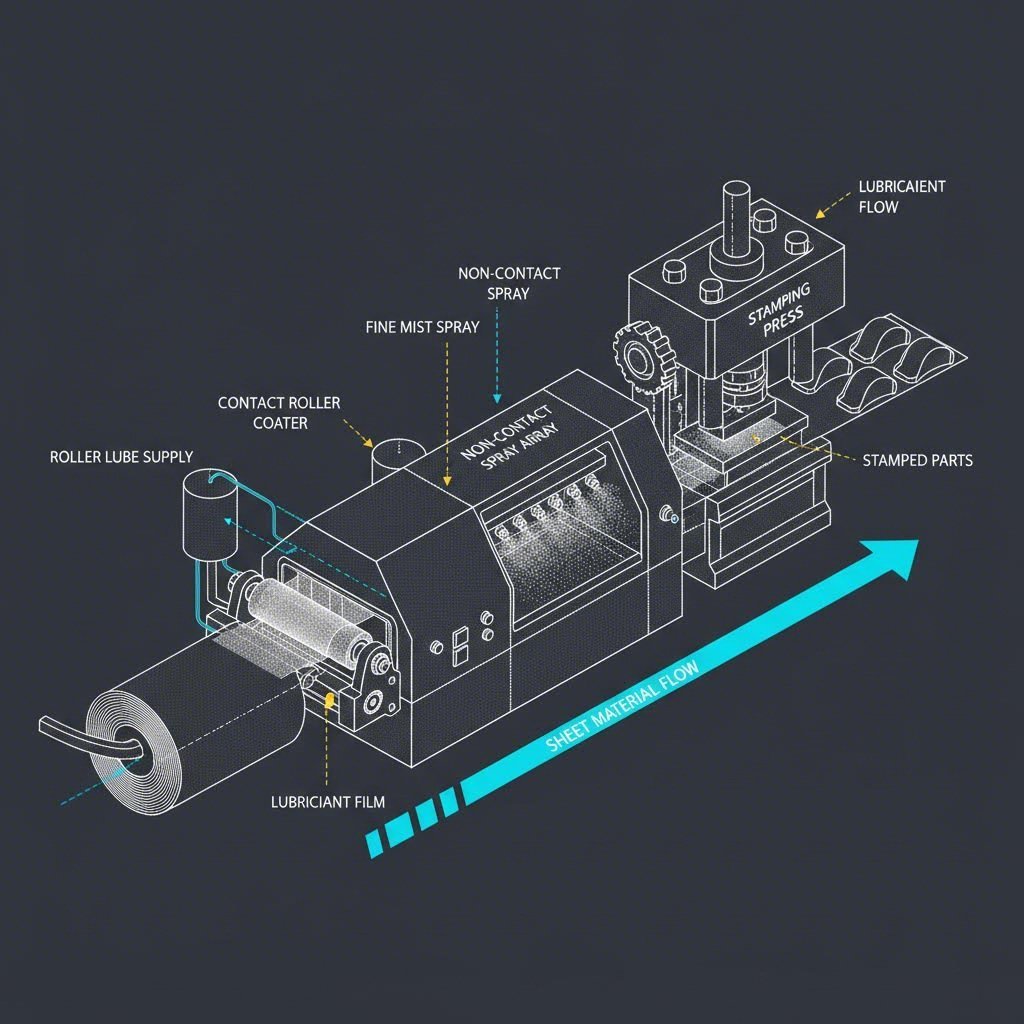

Even the perfect chemical formulation will fail if applied incorrectly. The mantra for application is "the right amount, in the right place, at the right time." Inconsistent coverage leads to localized tool wear and part cracking, while over-application creates safety hazards and waste.

Roller Coaters (Contact): Ideally suited for flat blanks and coil stock, roller systems physically touch the metal to apply a consistent, even film. They are highly efficient and minimize misting, keeping the shop floor cleaner. Roller coaters typically require 12 to 15 inches of line space and are excellent for ensuring total surface coverage. However, they can be limited when trying to lubricate specific trouble spots on a complex shaped part.

Spray Systems (Non-Contact): For complex geometries or when specific die areas need extra lubrication, spray systems are superior. Modern airless or electrostatic spray systems can target precise zones without touching the metal, reducing the risk of marking the surface. This is critical for Class A automotive surfaces where visual perfection is mandatory. The challenge with spray systems is managing overspray; without proper enclosure and mist collection, they can significantly degrade air quality and waste expensive fluid.

Post-Process Compatibility: Cleaning & Joining

A stamping lubricant’s job is not finished when the part leaves the press. It must remain compatible with downstream operations like welding, structural bonding, and painting. In the automotive sector, this is often the deciding factor.

Weldability and Bonding: Structural adhesives are increasingly used to join aluminum parts. Lubricant residues must be compatible with these adhesives, or they must be easily washable. Recent industry shifts have seen the development of blank-wash oils specifically designed to enhance adhesive bonding for aluminum, replacing older steel-centric oils that interfered with joint integrity.

Cleaning and EHS: The washability of a lubricant is measured by how easily it can be removed in a standard alkaline bath. Straight oils with heavy chlorinated paraffins are notoriously difficult to clean and pose environmental disposal challenges. Consequently, many OEMs are mandating chlorine-free fluids to avoid the high costs associated with hazardous waste disposal. To validate compatibility, stampers should perform a "stain test": soaking a sample coupon in the lubricant for 24 hours to check for discoloration or etching, which could signal potential paint adhesion failures later.

Testing & Validation: Ensuring Performance

Before committing to a lubricant for a full production run, rigorous testing is required to verify tribological performance. Relying solely on data sheets is insufficient for critical automotive components.

- Cup Draw Test: A standard method where a punch draws a cup from a flat blank until fracture. It measures the lubricant's ability to facilitate metal flow under tension.

- Twist-Compression Test: Evaluates the lubricant's film strength under rotation and pressure, simulating the friction seen in deep drawing operations.

- 4-Ball Wear Test: Primarily used to measure the extreme pressure (EP) properties of a fluid, indicating how well it protects tooling under high loads.

Moving from the lab to the floor involves a pilot run. Engineers should monitor for "hydraulic sticking" (where parts stick to the die due to excess fluid) and "galling" (aluminum buildup on the tool). Successful validation means the lubricant passes all three hurdles: it forms the part within tolerance, it washes off in the existing cleaning line, and it allows for defect-free welding and painting.

Summary: Making the Final Decision

Selecting the right lubricant for automotive stamping is a balancing act between tribology and process engineering. It requires a holistic view that considers the material properties (Al vs. Steel), the precision of the application system, and the rigorous demands of downstream assembly. By prioritizing chlorine-free chemistries and matching viscosity to press dynamics, manufacturers can optimize both part quality and operational efficiency.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Is lubricant required for all types of metal stamping?

Yes, virtually all metal stamping operations require some form of lubrication to reduce friction, dissipate heat, and protect tooling. Even "dry" stamping often uses a pre-applied mill oil or a specialized dry-film lubricant. Running without any lubricant typically leads to rapid tool wear, part scoring, and catastrophic failure, especially with materials like aluminum or high-strength steel.

2. What type of lubricant is best for aluminum automotive parts?

For Aluminum Body-in-White (BIW) parts, the industry standard is moving toward chlorine-free soluble oils or hot-melt lubricants. These provide the necessary boundary lubrication to prevent galling while being easier to clean and more environmentally friendly than traditional heavy straight oils. Hot-melt options are particularly effective for deep-draw closures.

3. How does lubricant viscosity affect stamping quality?

Viscosity controls the film thickness. If the viscosity is too high (>40 cSt), it can cause a "hydraulic effect," preventing the metal from fully forming into the die and causing dimensional inaccuracies. Conversely, if the viscosity is too low, the film may break down under pressure, leading to metal-on-metal contact and scoring. Light-viscosity oils (<20 cSt) are often preferred for high-speed, precision stamping.

4. What is the difference between straight oil and water-soluble stamping fluids?

Straight oils are 100% oil-based and offer maximum lubricity for severe operations but are difficult to clean and offer poor cooling. Water-soluble fluids (emulsions) contain water, providing excellent cooling and easier washability, making them ideal for high-speed operations where heat generation is a concern. Water-soluble fluids are generally more compatible with downstream welding and painting processes.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —