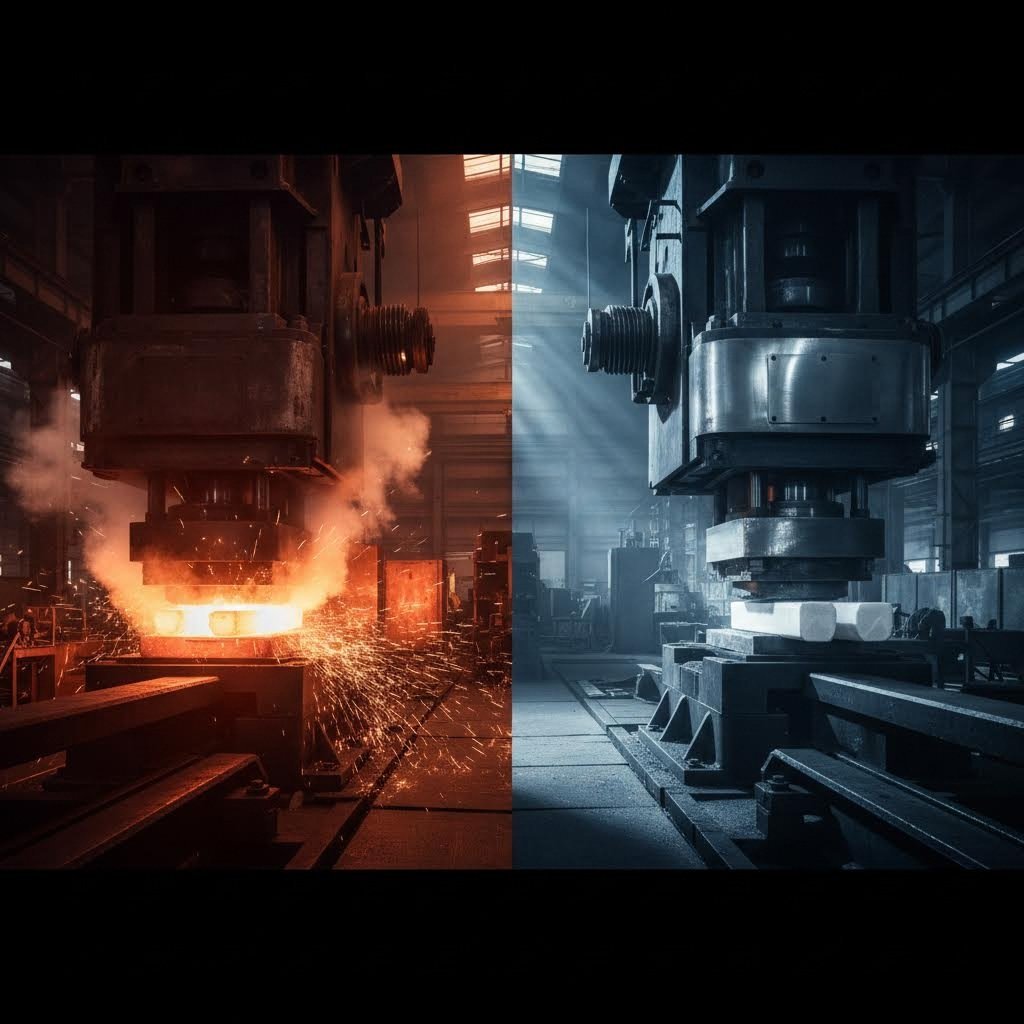

Hot Vs Cold: Key Differences Between Hot And Cold Forging Revealed

Understanding Metal Forging and the Temperature Factor

What is forging metal, exactly? Imagine shaping a piece of malleable metal into a precise form—not by cutting or melting it, but by applying controlled force through hammering, pressing, or rolling. This is the essence of metal forging, one of the oldest and most effective manufacturing processes still used today. What is a forging? Simply put, it's a component created through this deformation process, resulting in parts with exceptional strength and durability.

But here's the critical question: what separates hot forging from cold forging? The answer lies in one fundamental factor—temperature. The forging temperature at which metal is worked determines everything from how easily it flows to the final mechanical properties of your finished component.

Why Temperature Defines Every Forging Process

When you heat metal, something remarkable happens at the molecular level. The material becomes more malleable, requiring less force to shape. Cold forging, performed at or near room temperature, demands significantly higher pressures but delivers superior dimensional accuracy and surface finish. Hot forging, conducted at elevated temperatures (typically around 75% of the metal's melting point), allows for complex geometries and easier deformation but requires more energy.

Understanding what is the forging process at different temperatures helps engineers and manufacturers select the optimal method for each application. The dividing line between these two approaches isn't arbitrary—it's rooted in metallurgical science.

The Recrystallization Threshold Explained

The key to understanding the differences between hot and cold forging lies in a concept called the recrystallization temperature. This threshold represents the point at which a deformed metal's grain structure transforms into new, strain-free crystals.

Recrystallization is defined as the formation of a new grain structure in a deformed material by the formation and migration of high angle grain boundaries driven by the stored energy of deformation.

When forging occurs above this temperature, the metal continuously recrystallizes during deformation, preventing work hardening and maintaining excellent formability. This is hot forging. When forging happens below this threshold—typically at room temperature—the metal retains its deformed grain structure, becoming stronger through strain hardening. This is cold forging.

The recrystallization temperature isn't fixed for all metals. It depends on factors including alloy composition, the degree of prior deformation, and even impurity levels. For example, adding just 0.004% iron to aluminum can increase its recrystallization temperature by around 100°C. This variability makes understanding your specific material essential when choosing between forging methods.

Hot Forging Process and Temperature Requirements

Now that you understand the recrystallization threshold, let's explore what happens when metal is heated above this critical point. Hot forging transforms rigid metal billets into highly workable material that flows almost like clay under pressure. But achieving optimal results requires precise control of the forging temp for each specific alloy.

How Heating Transforms Metal Workability

When you heat metal to its hot forging temperature range, several remarkable changes occur. The material's yield strength drops significantly, meaning it takes far less force to deform. This reduction in resistance allows hot forging presses to shape complex geometries that would be impossible to achieve through cold working.

Here's what happens at the molecular level: heating causes atoms to vibrate more rapidly, weakening the bonds between them. The metal's crystalline structure becomes more mobile, and dislocations—the microscopic defects that enable plastic deformation—can move freely through the material. According to research from ScienceDirect, as the work-piece temperature approaches the melting point, the flow stress and energy required to form the material decreases substantially, enabling increased production rates.

Hot forgings benefit from a unique phenomenon: recrystallization and deformation occur simultaneously. This means the metal continuously regenerates its grain structure during shaping, preventing the strain hardening that would otherwise make further deformation difficult. The result? You can achieve dramatic shape changes in fewer operations compared to cold forging.

Another advantage is the breakdown of the original cast grain structure. During hot forging, the coarse grains from casting are replaced by finer, more uniform grains. This refinement directly enhances the mechanical properties of your finished component—improving both strength and ductility.

Temperature Ranges for Common Forging Alloys

Getting the steel forging temp right—or the temperature for any alloy you're working with—is essential for successful hot forging. Heat too little, and the metal won't flow properly, potentially causing cracks. Heat too much, and you risk grain growth or even melting. Here are the optimal temperature ranges for forging steel and other common metals, based on data from Caparo:

| Metal Type | Hot Forging Temperature Range | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Steel Alloys | Up to 1250°C (2282°F) | Most common hot forging material; requires controlled cooling to prevent deformation |

| Aluminum Alloys | 300–460°C (572–860°F) | Rapid cooling rate; benefits from isothermal forging techniques |

| Titanium Alloys | 750–1040°C (1382–1904°F) | Susceptible to gas contamination; may require controlled atmosphere |

| Copper Alloys | 700–800°C (1292–1472°F) | Good formability; isothermal forging possible with quality die grades |

Notice the significant variation in the forging temperature of steel compared to aluminum. Steel requires temperatures nearly three times higher, which directly impacts equipment requirements, energy consumption, and die material selection. The temperature for forging steel must remain consistently above a minimum threshold throughout the operation—if it drops too low, ductility decreases dramatically and cracks may form.

To maintain proper forging temp throughout the process, all tooling is typically preheated. This minimizes temperature loss when the hot billet contacts the dies. In advanced applications like isothermal forging, the dies are maintained at the same temperature as the work-piece, allowing for exceptional precision and reduced geometric allowances.

Equipment and Force Considerations

Hot forging presses can operate with significantly lower tonnage requirements compared to cold forging equipment. Why? Because the heated metal's reduced yield strength means less force is needed to achieve deformation. This translates to several practical advantages:

- Smaller, less expensive press equipment for equivalent part sizes

- Ability to form complex shapes in single operations

- Reduced die stress and longer tool life (when dies are properly heated)

- Higher production rates due to faster material flow

However, hot forging introduces unique challenges. The process requires heating furnaces or induction heaters, proper atmosphere control to prevent oxidation, and careful management of scale formation on the work-piece surface. For reactive metals like titanium, protection from gas contamination—including oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen—may necessitate glass coatings or inert gas environments.

Understanding these equipment considerations becomes crucial when comparing hot forging to cold alternatives—a comparison that requires examining how cold forging mechanics differ fundamentally in their approach to metal deformation.

Cold Forging Mechanics and Material Behavior

While hot forging relies on elevated temperatures to soften metal, cold forging takes the opposite approach—shaping material at or near room temperature through sheer compressive force. This cold forming process demands significantly higher pressures, often ranging from 500 to 2000 MPa, but delivers remarkable benefits in precision, surface quality, and mechanical strength that hot forging simply cannot match.

So what exactly happens when you cold forge a component? The metal undergoes plastic deformation without the benefit of heat-induced softening. This creates a unique phenomenon that fundamentally changes the material's properties—and understanding this mechanism reveals why cold forged parts often outperform their hot-forged counterparts in specific applications.

Work Hardening and Strength Enhancement

Here's where cold forging becomes fascinating. Unlike hot forging, where recrystallization continuously refreshes the grain structure, cold deformation permanently alters the metal at the atomic level. As you compress the material, dislocations—microscopic defects in the crystal lattice—multiply and become entangled. This dislocation density increase is the mechanism behind strain hardening, also called work hardening.

Imagine trying to move through a crowded room. With few people (dislocations), movement is easy. Pack the room full, and movement becomes restricted. The same principle applies to metal: as dislocations accumulate during cold forming processes, they obstruct each other's movement, making further deformation increasingly difficult—and the material progressively stronger.

According to research from Total Materia, this improvement in mechanical properties can be so substantial that material grades previously deemed unsuitable for machining, warm forging, or hot forging may develop appropriate mechanical properties for new applications after cold forming. The enhancement correlates directly with the amount and type of deformation applied—areas experiencing greater deformation show more significant strength gains.

The cold-forming process delivers several key mechanical property improvements:

- Increased tensile strength – Work hardening elevates the material's resistance to pulling forces

- Enhanced yield strength – The point at which permanent deformation begins rises significantly

- Improved hardness – Surface and core hardness increase without heat treatment

- Superior fatigue resistance – Refined grain flow patterns enhance cyclic load performance

- Optimized grain structure – Continuous grain flow follows component contours, eliminating weak points

This natural strengthening through metal cold forming often eliminates the need for subsequent heat treatment cycles. The component emerges from the die already hardened—saving both time and processing costs.

Achieving Tight Tolerances Through Cold Forming

Precision is where cold forging truly shines. Because the process occurs at room temperature, you avoid the dimensional variations caused by thermal expansion and contraction. When hot forged parts cool, they shrink unpredictably, requiring generous machining allowances. Cold forged components maintain their as-formed dimensions with remarkable consistency.

How precise can cold forging get? The process routinely achieves tolerances of IT6 to IT9—comparable to machined components—with surface finishes ranging from Ra 0.4 to 3.2 μm. This near-net-shape capability means many cold forged parts require minimal or no secondary machining, dramatically reducing production costs and lead times.

The surface quality advantage stems from the absence of oxide scale formation. In hot forging, the heated metal reacts with atmospheric oxygen, creating a rough, scaled surface that must be removed. Cold forming operates below oxidation temperatures, preserving the original material surface and often improving it through the polishing action of the dies.

Material utilization rates tell another compelling story. Cold forging achieves up to 95% material utilization, compared to the 60-80% typical of hot forging with its flash and scale losses. For high-volume production where material costs multiply across thousands of parts, this efficiency advantage becomes significant.

Material Considerations and Limitations

Not every metal is suited to the cold-forming process. The technique works best with ductile materials that can withstand substantial plastic deformation without cracking. According to Laube Technology, metals like aluminum, brass, and low-carbon steel are ideal for cold forging due to their ductility at room temperature.

The most commonly cold forged materials include:

- Low-carbon steels – Excellent formability with carbon content typically below 0.25%

- Boron steels – Enhanced hardenability after forming

- Aluminum alloys – Lightweight with good cold forming characteristics

- Copper and brass – Superior ductility enables complex shapes

- Precious metals – Gold, silver, and platinum respond well to cold working

Brittle materials like cast iron are not suitable for cold forging—they'll crack under the intense compressive forces rather than flow plastically. High-alloy steels and stainless steels present challenges due to their increased work-hardening rates, though specialized processes can accommodate them in certain applications.

One important consideration: while cold forging strengthens the material, it simultaneously reduces ductility. The same dislocation buildup that increases strength also limits the metal's ability to undergo further deformation. Complex geometries may require multiple forming stages with intermediate annealing treatments to restore workability—adding to processing time and cost.

This tradeoff between forming capability and final properties leads many manufacturers to consider a third option: warm forging, which occupies the strategic middle ground between hot and cold methods.

Warm Forging as a Strategic Middle Ground

What happens when cold forging can't handle the complexity you need, but hot forging sacrifices too much precision? This is exactly where warm forging enters the picture—a hybrid forging operation that combines the best characteristics of both temperature extremes while minimizing their respective drawbacks.

When comparing hot working vs cold working, most discussions present a binary choice. But experienced manufacturers know that this middle-ground approach often delivers optimal results for specific applications. Understanding when and why to choose warm forging can significantly impact your production efficiency and part quality.

When Neither Hot Nor Cold Is Optimal

Consider this scenario: you need to produce a precision gear component that requires tighter tolerances than hot forging can deliver, but the geometry is too complex for cold forging's force limitations. This is precisely where warm forging shines.

According to Queen City Forging, the temperature range for warm forging of steel extends from about 800 to 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit, depending on the alloy. However, the narrower range of 1,000 to 1,330 degrees Fahrenheit is emerging as the range of greatest commercial potential for warm forging of steel alloys.

This intermediate temperature—above a household oven but below the recrystallization point—creates unique processing conditions. The metal gains enough ductility to flow into moderately complex shapes while retaining sufficient rigidity to maintain dimensional accuracy. It's the Goldilocks zone of hot forming techniques.

The forging operation at warm temperatures addresses several pain points that manufacturers encounter with pure hot or cold methods:

- Reduced tooling loads – Lower forces than cold forging extend die life

- Reduced forging press loads – Smaller equipment requirements than cold forging

- Increased steel ductility – Better material flow than room-temperature processing

- Elimination of pre-forging annealing – No need for the intermediate heat treatments cold forging often requires

- Favorable as-forged properties – Often eliminates post-forging heat treatment entirely

Balancing Formability With Surface Quality

One of warm forging's most significant advantages lies in its surface quality outcomes. When comparing hot work vs cold work results, hot forging produces scale-covered surfaces requiring extensive cleanup, while cold forging delivers pristine finishes but limits geometric complexity. Warm forging threads the needle between these extremes.

At intermediate temperatures, oxidation occurs at a much slower rate than during hot forging. According to Frigate, this reduced oxidation results in minimal scaling, which improves surface quality and extends the lifespan of forging dies—reducing tooling costs significantly. The cleaner surface also reduces time and cost associated with post-forging treatments.

Dimensional accuracy represents another compelling advantage. Hot forging causes substantial thermal expansion and contraction, making tight tolerances challenging. Warm forging reduces this thermal distortion dramatically. The metal undergoes less expansion and contraction, enabling near-net-shape production where the final part is much closer to desired dimensions—significantly reducing secondary machining requirements.

From a materials perspective, warm forging opens doors that cold forging keeps closed. Steels that would crack under cold forging pressures become workable at elevated temperatures. Aluminum alloys that would oxidize excessively during hot forging maintain better surface integrity in the warm range. This expanded material compatibility makes warm forging particularly valuable for manufacturers working with challenging alloys.

Energy efficiency adds another dimension to the warm forging advantage. Heating material to intermediate temperatures requires considerably less energy than hot forging temperatures. For companies focused on reducing their carbon footprint or managing operational expenses, this translates directly to lower costs and improved sustainability metrics.

Real-world applications demonstrate warm forging's value. In automotive manufacturing, transmission gears and precision bearings frequently utilize warm forging because these components demand the tight tolerances that hot forging cannot achieve, combined with the geometric complexity that cold forging cannot accommodate. The resulting parts require minimal post-processing while meeting stringent performance specifications.

With warm forging positioned as the strategic middle option, the next logical step is comparing all three methods directly—examining how hot and cold forging stack up across the performance metrics that matter most for your specific applications.

Direct Comparison of Hot and Cold Forging Performance

You've explored hot forging, cold forging, and the warm middle ground—but how do they truly stack up against each other? When evaluating hot forging vs cold forging for your specific project, the decision often comes down to measurable performance factors rather than theoretical advantages. Let's break down the critical differences that will ultimately determine which method delivers the results you need.

The table below provides a comprehensive side-by-side comparison of the key performance parameters. Whether you're manufacturing components forged in metal for automotive applications or precision parts requiring tight specifications, these metrics will guide your decision-making process.

| Performance Factor | Hot Forging | Cold Forging |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature Range | 700°C–1250°C (1292°F–2282°F) | Room temperature to 200°C (392°F) |

| Dimensional Tolerances | ±0.5mm to ±2mm typical | ±0.05mm to ±0.25mm (IT6–IT9) |

| Surface Finish Quality | Rough (requires post-processing); Ra 6.3–25 μm | Excellent; Ra 0.4–3.2 μm |

| Material Flow Characteristics | Excellent flow; complex geometries possible | Limited flow; simpler geometries preferred |

| Tooling Wear Rates | Moderate (heat-related wear) | Higher (extreme pressure-related wear) |

| Energy Consumption | High (heating requirements) | Lower (no heating required) |

| Material Utilization | 60–80% (flash and scale losses) | Up to 95% |

| Press Force Required | Lower tonnage for equivalent parts | Higher tonnage (500–2000 MPa typical) |

Surface Finish and Tolerance Comparison

When precision matters most, the difference between cold formed and hot rolled steel—or any forged material—becomes immediately apparent. Cold forging delivers surface finishes that can rival machined components, with roughness values as low as Ra 0.4 μm. Why such a dramatic difference? The answer lies in what happens at the material surface during each process.

During hot forging, the heated metal reacts with atmospheric oxygen, forming oxide scale on the surface. According to research from the International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology, this scale formation creates irregular depositions that require removal through grinding, shot blasting, or machining. The resulting surface—even after cleaning—rarely matches cold forging's as-formed quality.

Cold forging avoids oxidation entirely. The dies actually polish the workpiece surface during forming, often improving the original billet finish. For cold forged steel components requiring aesthetic appeal or precise mating surfaces, this eliminates secondary finishing operations entirely.

Dimensional accuracy follows a similar pattern. Hot forging involves significant thermal expansion during processing, followed by contraction during cooling. This thermal cycling introduces dimensional variability that's difficult to control precisely. Manufacturers typically add machining stock of 1–3mm to hot forged parts, expecting to remove material in secondary operations.

Cold forging eliminates thermal distortion. The workpiece maintains room temperature throughout processing, so what comes out of the die matches what was designed—within tolerances as tight as ±0.05mm for precision applications. This near-net-shape capability directly reduces machining time, material waste, and production costs.

Mechanical Property Differences

Here's where the comparison becomes nuanced. Both hot and cold forging produce mechanically superior parts compared to casting or machining from bar stock—but they achieve this through fundamentally different mechanisms.

Hot forging refines the grain structure through recrystallization. The process breaks down the coarse, dendritic grain pattern from casting and replaces it with finer, more uniform grains aligned with the part geometry. According to Triton Metal Alloys, this transformation enhances mechanical properties and makes the metal less prone to cracking—excellent toughness for high-stress applications.

Cold forging strengthens through work hardening. The accumulated dislocations from plastic deformation at room temperature increase tensile strength, yield strength, and hardness simultaneously. The trade-off? Reduced ductility compared to the original material. For applications where forged strength and wear resistance matter more than flexibility, cold forged steel delivers exceptional performance without requiring heat treatment.

Consider these mechanical property outcomes:

- Hot forging – Superior toughness, impact resistance, and fatigue life; maintains ductility; ideal for components subjected to dynamic loading

- Cold forging – Higher hardness and tensile strength; work-hardened surface resists wear; optimal for precision components under static or moderate loads

The grain flow pattern also differs meaningfully. Hot forging produces continuous grain flow that follows complex contours, maximizing strength in critical areas. Cold forging achieves similar grain orientation benefits but is limited to geometries that don't require extreme material flow.

Quality Control and Common Defect Types

Every manufacturing process has characteristic failure modes, and understanding these helps you implement appropriate quality controls. The defects encountered in cold forging vs hot forging reflect the unique stresses and conditions each process creates.

Hot Forging Defects

- Scale pits – Irregular surface depressions caused by oxide scale pressed into the metal; prevented through adequate surface cleaning

- Die shift – Misalignment between upper and lower dies creating dimensional inaccuracy; requires proper die alignment verification

- Flakes – Internal cracks from rapid cooling; controlled through proper cooling rates and procedures

- Surface cracking – Occurs when forging temperature drops below the recrystallization threshold during processing

- Incomplete forging penetration – Deformation occurs only at the surface while the interior retains cast structure; caused by using light hammer blows

Cold Forging Defects

- Cold shut in forging – This characteristic defect occurs when metal folds onto itself during forming, creating a visible crack or seam at corners. According to IRJET research, cold shut defects arise from improper die design, sharp corners, or excessive chilling of the forged product. Prevention requires increasing fillet radii and maintaining proper working conditions.

- Residual stresses – Uneven stress distribution from non-uniform deformation; may require stress-relief annealing for critical applications

- Surface cracking – Material exceeds its ductility limits; addressed through material selection or intermediate annealing

- Tool breakage – Extreme forces can fracture dies; requires proper tooling design and material selection

Production and Cost Considerations

Beyond technical performance, practical production factors often tip the scales in method selection. Cold forging typically commands higher initial tooling investments—the dies must withstand tremendous forces and require premium tool steel grades. However, the elimination of heating equipment, faster cycle times, and reduced material waste often make it more economical for high-volume production runs.

Hot forging requires significant energy input for heating but operates with lower press tonnage requirements. For larger parts or those with complex geometries that would crack under cold forging conditions, hot forging remains the only viable option despite higher per-piece energy costs.

According to industry analysis, cold forging is generally more cost-effective for precision parts and high volumes, while hot forging may be better suited for larger or more intricate forms with lower volume requirements. The break-even point depends on part geometry, material type, production quantity, and tolerance specifications.

With these performance comparisons established, the next critical step is understanding which materials respond best to each forging method—guidance that becomes essential when matching your specific alloy requirements to the optimal process.

Material Selection Guide for Forging Methods

Understanding the performance differences between hot and cold forging is valuable—but how do you apply that knowledge to your specific material? The truth is, material properties often dictate which forging method will succeed or fail. Choosing the wrong approach can result in cracked components, excessive tool wear, or parts that simply don't meet mechanical specifications.

When forging metals, each alloy family behaves differently under compressive forces and temperature variations. Some materials practically demand hot forging due to brittleness at room temperature, while others perform optimally through cold forming processes. Let's examine the key material categories and provide actionable guidance for selecting the right forging approach.

| Material Type | Optimal Forging Method | Temperature Considerations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Carbon Steel | Cold or Hot | Cold: Room temp; Hot: 900–1250°C | Fasteners, automotive components, general machinery |

| Alloy Steel | Hot (primarily) | 950–1200°C depending on alloy | Gears, shafts, crankshafts, aerospace components |

| Stainless Steel | Hot | 900–1150°C | Medical devices, food processing, corrosion-resistant parts |

| Aluminum Alloys | Cold or Warm | Cold: Room temp; Warm: 150–300°C | Aerospace structures, automotive lightweighting, electronics |

| Titanium Alloys | Hot | 750–1040°C | Aerospace, medical implants, high-performance racing |

| Copper Alloys | Cold or Hot | Cold: Room temp; Hot: 700–900°C | Electrical connectors, plumbing, decorative hardware |

| Brass | Cold or Warm | Cold: Room temp; Warm: 400–600°C | Musical instruments, valves, decorative fittings |

Steel Alloy Forging Recommendations

Steel remains the backbone of forging metal operations worldwide—and for good reason. According to Creator Components, carbon steel has become one of the most common materials in drop forging because of its strength, toughness, and machinability. But which forging method works best depends heavily on the specific steel grade you're working with.

Low-carbon steels (typically below 0.25% carbon) offer exceptional versatility. Their ductility at room temperature makes them ideal candidates for cold forging steel applications—think fasteners, bolts, and precision automotive components. The work-hardening effect during cold forming actually strengthens these softer grades, often eliminating the need for subsequent heat treatment.

What about higher carbon content? As carbon levels increase, ductility decreases and brittleness rises. Medium and high-carbon steels generally require hot forging to prevent cracking under compressive forces. The elevated temperature restores formability while enabling complex geometric shapes.

Alloy steels present more complex considerations. According to the material selection guide from Creator Components, alloy steel adds elements like nickel, chromium, and molybdenum to enhance strength, durability, and corrosion resistance. These additions typically increase work-hardening rates, making hot forging the preferred approach for most alloy steel applications.

Heat treated steel forging represents a critical consideration for performance-demanding applications. Forged steel components destined for heat treatment should be processed with the final thermal cycle in mind. Hot forging creates a refined grain structure that responds favorably to subsequent quenching and tempering operations, maximizing the mechanical property improvements from heat treatment.

Key steel forging recommendations:

- Carbon steels below 0.25% C – Excellent cold forging candidates; work hardening provides strength enhancement

- Medium-carbon steels (0.25–0.55% C) – Warm or hot forging preferred; cold forging possible with intermediate annealing

- High-carbon steels (above 0.55% C) – Hot forging required; too brittle for cold working

- Alloy steels – Hot forging primary method; enhanced properties justify higher processing costs

- Stainless steels – Hot forging recommended; high work-hardening rates limit cold forming applications

Non-Ferrous Metal Forging Guidelines

Moving beyond steel, non-ferrous metals offer distinct advantages—and present unique forging challenges. Their material properties often open doors to cold forging applications that steel keeps firmly closed.

Aluminum alloys stand out as exceptional cold forging candidates. According to The Federal Group USA, aluminum and magnesium offer the ideal physical properties for cold forging because they are lightweight, highly ductile, and have low work-hardening rates. These characteristics allow them to deform easily under pressure without requiring high temperatures.

When cold forging aluminum, you'll notice the material flows readily into complex shapes while maintaining excellent surface finish. The process works particularly well for:

- Automotive suspension components and brackets

- Aerospace structural elements where weight savings matter

- Electronic housings and heat sinks

- Consumer product enclosures

However, aluminum's thermal characteristics introduce considerations for hot forging. The narrow working temperature range (300–460°C) and rapid cooling rate demand precise temperature control. Isothermal forging techniques—where dies are maintained at workpiece temperature—often deliver the best results for complex aluminum components.

Titanium alloys occupy the opposite end of the spectrum. According to industry guidance, titanium is favored in aviation, aerospace, and medical applications due to its light weight, high strength, and good corrosion resistance. Although titanium has excellent properties, it is expensive and difficult to process.

Hot forging is essentially mandatory for titanium. The material's limited ductility at room temperature causes cracking under cold forging conditions. More critically, titanium readily absorbs oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen at elevated temperatures, potentially degrading mechanical properties. Successful titanium forging requires controlled atmospheres or protective glass coatings to prevent gas contamination.

Forging copper and its alloys offers surprising flexibility. Copper's excellent ductility enables both cold and hot forging, with method selection depending on specific alloy composition and part requirements. Pure copper and high-copper alloys cold forge beautifully, making them ideal for electrical connectors and precision terminals where conductivity and dimensional accuracy both matter.

According to Creator Components, copper is easy to process and has excellent corrosion resistance, but it is not as strong as steel and easily deforms under high stress conditions. This limitation makes copper components best suited for electrical and thermal applications rather than structural load-bearing uses.

Brass (copper-zinc alloy) represents another versatile option. Its high strength, ductility, and aesthetic properties make it suitable for decorative hardware, musical instruments, and plumbing fixtures. Cold forging produces excellent surface finishes on brass components, while warm forging enables more complex geometries without the oxidation issues of hot processing.

When Material Properties Dictate Method Selection

Sounds complex? The decision often simplifies when you focus on three fundamental material characteristics:

Ductility at room temperature – Materials that can undergo significant plastic deformation without cracking (low-carbon steel, aluminum, copper, brass) are natural cold forging candidates. Brittle materials or those with high work-hardening rates (high-carbon steel, titanium, some stainless grades) require elevated temperatures.

Work-hardening behavior – Materials with low work-hardening rates remain formable through multiple cold forging operations. Those that harden rapidly may crack before achieving the desired geometry—unless you introduce intermediate annealing cycles or switch to hot processing.

Surface reactivity – Reactive metals like titanium that absorb gases at elevated temperatures introduce contamination risks during hot forging. Aluminum oxidizes rapidly above certain temperatures. These factors influence not just method selection but also the specific temperature ranges and atmospheric controls required.

According to Frigate's material selection guide, the ideal choice depends on the unique needs of your application—considering factors like operating environment, load requirements, corrosion exposure, and cost constraints. There's no single best forging material; matching material properties to forging method requires balancing performance requirements against processing realities.

With material selection guidance established, the next critical consideration becomes the equipment and tooling required to execute each forging method successfully—investments that significantly impact both initial costs and long-term production economics.

Equipment and Tooling Requirements by Forging Type

You've selected your material and determined whether hot or cold forging best suits your application—but can your equipment handle the job? The differences between hot and cold forging extend far beyond temperature settings. Each method demands fundamentally different press equipment, tooling materials, and maintenance protocols. Understanding these requirements helps you avoid costly equipment mismatches and plan realistic capital investments.

Whether you're evaluating a cold forging press for high-volume fastener production or sizing hot forging equipment for complex automotive components, the decisions you make here directly impact production capacity, part quality, and long-term operational costs.

Press Equipment and Tonnage Requirements

The force required to deform metal varies dramatically between hot and cold forging—and this difference drives equipment selection more than any other factor. Cold forging presses must generate tremendous tonnage because room-temperature metal resists deformation aggressively. Hot forging presses, working with softened material, can achieve equivalent deformation with significantly lower forces.

According to technical analysis from CNZYL, cold forging requires massive presses—often thousands of tons—to overcome the high flow stresses of room-temperature metal. This tonnage requirement directly influences equipment costs, facility requirements, and energy consumption.

Here's what each forging method typically requires in terms of equipment:

Cold Forging Equipment Categories

- Cold forging presses – Mechanical or hydraulic presses rated from 500 to 6,000+ tons; higher tonnage required for larger parts and harder materials

- Cold forging machines – Multi-station headers capable of producing thousands of parts per hour for high-volume applications

- Cold forming presses – Specialized equipment designed for progressive forming operations with multiple die stations

- Transfer presses – Automated systems that move workpieces between forming stations

- Straightening and sizing equipment – Secondary equipment for final dimensional adjustments

Hot Forging Equipment Categories

- Hot forging presses – Hydraulic or mechanical presses typically rated from 500 to 50,000+ tons; lower tonnage-per-part-size ratio than cold forging

- Forging hammers – Drop hammers and counterblow hammers for high-energy impact forming

- Heating equipment – Induction heaters, gas furnaces, or electric furnaces for billet preheating

- Die heating systems – Equipment to preheat dies and maintain working temperature

- Descaling systems – Equipment to remove oxide scale before and during forging

- Controlled cooling systems – For managing post-forge cooling rates to prevent cracking

The cold forging press you select must match both your part geometry and material requirements. A press rated for aluminum components won't generate sufficient force for equivalent steel parts. Forging engineering calculations typically determine minimum tonnage requirements based on part cross-section, material flow stress, and friction factors.

Production speed presents another significant difference. Cold forging machines—particularly multi-station cold forming presses—achieve cycle rates measured in parts per second. A high-speed cold forging press can produce simple fasteners at rates exceeding 300 pieces per minute. Hot forging, with its heating cycles and material handling requirements, typically operates at considerably slower rates.

Tooling Investment Considerations

Beyond press equipment, tooling represents a critical investment that differs substantially between forging methods. The extreme pressures in cold forging demand premium die materials and sophisticated designs, while hot forging dies must withstand elevated temperatures and thermal cycling.

Cold forging tooling faces extraordinary stress. According to industry research, extremely high pressures necessitate expensive, high-strength tooling—often carbide grades—with sophisticated designs. Tool life can become a significant concern, with dies potentially requiring replacement or refurbishment after producing tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of parts.

| Tooling Factor | Cold Forging | Hot Forging |

|---|---|---|

| Die Material | Tungsten carbide, high-speed steel, premium tool steels | Hot-work tool steels (H-series), nickel-based superalloys |

| Initial Tooling Cost | Higher (premium materials, precision machining) | Moderate to high (heat-resistant materials) |

| Die Life | 50,000–500,000+ parts typical | 10,000–100,000 parts typical |

| Primary Wear Mechanism | Abrasive wear, fatigue cracking | Thermal fatigue, oxidation, heat checking |

| Maintenance Frequency | Periodic polishing and reconditioning | Regular inspection for thermal damage |

| Lead Time for New Tooling | 4–12 weeks typical | 4–10 weeks typical |

The die material selection directly impacts both initial investment and ongoing production costs. Carbide dies for cold forging machines command premium prices but deliver extended service life under the extreme pressures involved. Hot forging dies, made from H-series hot-work steels, cost less initially but require more frequent replacement due to thermal cycling damage.

Lubrication requirements also differ significantly. Cold forging relies on phosphate coatings and specialized lubricants to reduce friction and prevent galling between the die and workpiece. Hot forging uses graphite-based lubricants that can withstand elevated temperatures while providing adequate die release. Both lubrication systems add to operational costs but are essential for achieving acceptable tool life.

Production Volume and Lead Time Implications

How do equipment and tooling considerations translate into practical production decisions? The answer often comes down to volume requirements and time-to-production constraints.

Cold forging economics favor high-volume production. The substantial upfront investment in cold forging presses and precision tooling amortizes efficiently across large production runs. According to the technical comparison data, high-volume production strongly favors cold or warm forging due to the highly automated, continuous processes that enable extremely high throughput.

Consider these production scenarios:

- High volume (100,000+ parts annually) – Cold forging typically delivers lowest per-part cost despite higher tooling investment; automation maximizes efficiency

- Medium volume (10,000–100,000 parts) – Either method viable depending on part complexity; tooling amortization becomes a significant factor

- Low volume (under 10,000 parts) – Hot forging often more economical due to lower tooling costs; cold forging tooling investment may not justify itself

- Prototype quantities – Hot forging typically preferred for initial development; lower tooling lead times and costs

Lead time represents another critical consideration. New cold forging tooling often requires longer development cycles due to the precision required in die design and the multi-stage forming sequences common in complex parts. Hot forging dies, while still requiring careful engineering, typically involve simpler single-stage designs that can reach production faster.

Maintenance scheduling impacts production planning differently for each method. Cold forming presses require regular inspection and replacement of high-wear tooling components, but the equipment itself generally demands less maintenance than hot forging systems with their heating elements, refractory linings, and thermal management systems. Hot forging facilities must budget for furnace maintenance, descaling equipment upkeep, and more frequent die replacement cycles.

The forging engineering expertise required also varies. Cold forging demands precise control over material flow, friction conditions, and multi-stage forming sequences. Hot forging engineering focuses more on temperature management, grain flow optimization, and post-forge heat treatment specifications. Both disciplines require specialized knowledge that influences equipment setup, process development, and quality control procedures.

With equipment and tooling requirements understood, the practical question becomes: which industries actually apply these forging methods, and what real-world components emerge from each process?

Industry Applications and Component Examples

So what are forgings actually used for in the real world? Understanding the theoretical differences between hot and cold forging is valuable—but seeing these methods applied to actual components brings the decision-making process into sharp focus. From the suspension arms beneath your vehicle to the turbine blades in jet engines, the forging manufacturing process delivers critical components across virtually every industry that demands strength, reliability, and performance.

The advantages of forging become most apparent when examining specific applications. Each industry prioritizes different performance characteristics—automotive demands durability under dynamic loads, aerospace requires exceptional strength-to-weight ratios, and industrial equipment needs wear resistance and longevity. Let's explore how hot and cold forging serve these diverse requirements.

Automotive Component Applications

The automotive industry represents the largest consumer of forged components worldwide. According to Aerostar Manufacturing, cars and trucks may contain more than 250 forgings, most of which are produced from carbon or alloy steel. The metal forging process delivers the forged strength these safety-critical components demand—strength that cannot be replicated through casting or machining alone.

Why does forging dominate automotive manufacturing? The answer lies in the extreme conditions these components face. Engine parts experience temperatures exceeding 800°C and thousands of combustion cycles per minute. Suspension components absorb continuous shock loads from road impacts. Drivetrain elements transmit hundreds of horsepower while rotating at highway speeds. Only forged components consistently deliver the mechanical properties required for these demanding applications.

Hot Forging Applications in Automotive

- Crankshafts – The heart of the engine, converting linear piston motion into rotational power; hot forging produces the complex geometry and refined grain structure essential for fatigue resistance

- Connecting rods – Linking pistons to crankshafts under extreme cyclic loading; forged strength prevents catastrophic engine failure

- Suspension arms – Control arms and A-arms requiring exceptional toughness to absorb road impacts while maintaining precise wheel geometry

- Drive shafts – Transmitting torque from transmission to wheels; hot forging ensures uniform grain flow along the shaft length

- Axle beams and shafts – Supporting vehicle weight while transmitting driving forces; the steel forging process produces the necessary strength-to-weight ratio

- Steering knuckles and kingpins – Safety-critical steering components where failure is not an option

- Transmission gears – Complex tooth geometry and precise dimensions achieved through controlled hot forging

Cold Forging Applications in Automotive

- Wheel studs and lug nuts – High-volume precision fasteners produced at rates of hundreds per minute

- Valve bodies – Tight tolerances and excellent surface finish for hydraulic control systems

- Splined shafts – Precision external splines formed without machining

- Ball studs and socket components – Suspension linkage parts requiring dimensional accuracy

- Alternator and starter components – Precision parts benefiting from work-hardened strength

- Seat adjustment mechanisms – Cold forged for consistent quality and surface finish

For automotive manufacturers seeking reliable forging partners, companies like Shaoyi (Ningbo) Metal Technology exemplify the precision hot forging capabilities modern automotive production demands. Their IATF 16949 certification—the automotive industry's quality management standard—ensures consistent production of critical components including suspension arms and drive shafts. With rapid prototyping available in as little as 10 days, manufacturers can move quickly from design to production validation.

Aerospace and Industrial Uses

Beyond automotive, the aerospace industry pushes forging technology to its absolute limits. According to industry research, many aircraft are "designed around" forgings, and contain more than 450 structural forgings as well as hundreds of forged engine parts. The high strength-to-weight ratio and structural reliability improve performance, range, and payload capabilities of aircraft.

Aerospace applications demand materials and processes that can perform under conditions automotive components never experience. Jet turbine blades operate at temperatures between 1,000 and 2,000°F while spinning at incredible speeds. Landing gear absorbs massive impact forces during touchdown. Structural bulkheads must maintain integrity under constant pressurization cycles. The metal forging process creates components that meet these extraordinary requirements.

Hot Forging Dominates Aerospace Applications

- Turbine discs and blades – Nickel-base and cobalt-base superalloys forged for creep resistance at extreme temperatures

- Landing gear cylinders and struts – High-strength steel forgings capable of absorbing repeated impact loads

- Wing spars and bulkheads – Aluminum and titanium structural forgings providing strength with minimal weight

- Engine mounts and brackets – Critical load-bearing connections between engines and airframe

- Helicopter rotor components – Titanium and steel forgings withstanding continuous cyclic loading

- Spacecraft components – Titanium motor cases and structural elements for launch vehicles

Industrial equipment relies equally on forged components. The steel forging process produces parts for mining equipment, oil and gas extraction, power generation, and heavy construction machinery. These applications prioritize wear resistance, impact toughness, and long service life.

Industrial and Off-Highway Applications

- Mining equipment – Rock crusher components, excavator teeth, and drilling hardware subjected to extreme abrasive wear

- Oil and gas – Drill bits, valves, fittings, and wellhead components operating under high pressure and corrosive conditions

- Power generation – Turbine shafts, generator components, and steam valve bodies

- Construction equipment – Bucket teeth, track links, and hydraulic cylinder components

- Marine applications – Propeller shafts, rudder stocks, and anchor chain components

- Rail transportation – Wheel sets, axles, and coupling components

Matching Application Requirements to Forging Method

How do manufacturers determine which forging method suits each application? The decision typically follows from component requirements:

| Application Requirement | Preferred Forging Method | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| Complex geometry | Hot forging | Heated metal flows readily into intricate die cavities |

| Tight tolerances | Cold forging | No thermal distortion; near-net-shape capability |

| High production volume | Cold forging | Faster cycle times; automated multi-station production |

| Large part size | Hot forging | Lower force requirements; equipment limitations for cold |

| Superior surface finish | Cold forging | No scale formation; die polishing effect |

| Maximum toughness | Hot forging | Refined grain structure; recrystallization benefits |

| Work-hardened strength | Cold forging | Strain hardening increases hardness without heat treatment |

According to RPPL Industries, forging ensures tight tolerances and consistent quality, allowing manufacturers to produce automotive components with precise dimensions. This accuracy contributes to smooth engine performance, better fuel efficiency, and improved overall vehicle reliability. Additionally, forged parts are less prone to failure under extreme conditions, ensuring passenger safety and increased vehicle performance.

The forging manufacturing process continues evolving to meet changing industry demands. Electric vehicle adoption is driving new requirements for lightweight yet strong components. Aerospace manufacturers push for larger titanium forgings with tighter specifications. Industrial equipment demands longer service intervals and reduced maintenance. In each case, understanding the fundamental differences between hot and cold forging enables engineers to select the optimal method for their specific application requirements.

With these real-world applications established, the next step is developing a systematic approach to method selection—a decision framework that accounts for all the factors we've explored throughout this comparison.

Choosing the Right Forging Method for Your Project

You've explored the technical differences, examined material considerations, and reviewed real-world applications—but how do you translate all this knowledge into an actionable decision for your specific project? Selecting between hot and cold forging methods isn't about finding the universally "best" option. It's about matching your unique requirements to the process that delivers optimal results within your constraints.

What is cold forged versus hot forged when it comes to your particular component? The answer depends on a systematic evaluation of multiple factors working together. Let's build a decision-making framework that cuts through complexity and guides you toward the right choice.

Key Decision Criteria for Method Selection

Every forging project involves trade-offs. Tighter tolerances may require cold forging, but your geometry might demand hot processing. High volumes favor cold forge automation, yet material properties could push you toward elevated temperatures. The key is understanding which factors carry the most weight for your specific application.

According to research from the University of Strathclyde's systematic process selection methodology, manufacturing process capabilities are determined by manufacturing resource factors, work part material, and geometry factors. Generally, producing near boundaries of process capabilities requires more effort than operating within their usual range.

Consider these six critical decision criteria when evaluating forging methods:

1. Part Complexity and Geometry

How intricate is your component design? Cold forging excels at relatively simple geometries—cylindrical shapes, shallow recesses, and gradual transitions. The room-temperature metal resists dramatic flow, limiting the geometric complexity achievable in a single operation.

Hot forging opens doors to complex shapes. Heated metal flows readily into deep cavities, sharp corners, and intricate die features. If your design includes multiple directional changes, thin sections, or dramatic shape transitions, hot forging typically proves more feasible.

2. Production Volume Requirements

Volume dramatically influences method economics. Cold forging demands substantial tooling investment but delivers exceptional per-part efficiency at high volumes. According to Frigate's forging selection guide, cold forging is preferable for high-volume production runs due to its faster cycles and automated capabilities.

For prototype quantities or low-volume production, hot forging's lower tooling costs often prove more economical despite higher per-piece processing expenses.

3. Material Type and Properties

Your material choice may dictate the forging method before other factors come into play. Ductile materials like aluminum, low-carbon steel, and copper alloys respond well to cold forming processes. Brittle materials, high-alloy steels, and titanium typically require hot processing to prevent cracking.

4. Tolerance and Dimensional Requirements

How precise must your finished component be? Cold forging routinely achieves tolerances of ±0.05mm to ±0.25mm—often eliminating secondary machining entirely. Hot forging's thermal expansion and contraction typically limits tolerances to ±0.5mm or larger, requiring machining allowances for precision features.

5. Surface Finish Specifications

Surface quality requirements influence method selection significantly. Cold forging produces excellent as-formed finishes (Ra 0.4–3.2 μm) because no oxide scale forms at room temperature. Hot forging creates scaled surfaces requiring cleaning and often secondary finishing operations.

6. Budget and Timeline Constraints

Initial investment, per-part costs, and time-to-production all factor into the decision. Cold forging requires higher upfront tooling investment but delivers lower per-piece costs at volume. Hot forging offers faster tooling development and lower initial costs but higher ongoing operational expenses.

Decision Matrix: Weighted Factor Comparison

Use this decision matrix to systematically evaluate which forging method best matches your project requirements. Score each factor based on your specific needs, then weight according to priority:

| Decision Factor | Weight (1-5) | Cold Forging Favored When... | Hot Forging Favored When... |

|---|---|---|---|

| Part Complexity | Assign based on design | Simple to moderate geometry; gradual transitions; shallow features | Complex geometry; deep cavities; dramatic shape changes; thin sections |

| Production Volume | Assign based on quantity | High volume (100,000+ annually); automated production desired | Low to medium volume; prototype development; short production runs |

| Material Type | Assign based on alloy | Aluminum, low-carbon steel, copper, brass; ductile materials | High-alloy steel, stainless, titanium; materials with limited room-temp ductility |

| Tolerance Requirements | Assign based on specs | Tight tolerances required (±0.25mm or better); near-net-shape critical | Standard tolerances acceptable (±0.5mm or larger); secondary machining planned |

| Surface Finish | Assign based on requirements | Excellent finish required (Ra < 3.2 μm); minimal post-processing desired | Rough finish acceptable; subsequent finishing operations planned |

| Budget Profile | Assign based on constraints | Higher tooling investment acceptable; lowest per-part cost priority | Lower initial investment preferred; higher per-piece cost acceptable |

To use this matrix effectively: assign weights (1-5) to each factor based on importance to your project, then evaluate whether your requirements favor cold or hot forging for each criterion. The method accumulating higher weighted scores typically represents your optimal choice.

Matching Project Requirements to Forging Type

Let's apply this framework to common project scenarios. Imagine you're developing a new automotive fastener—high volume, tight tolerances, low-carbon steel material, excellent surface finish required. Every factor points toward cold forging as the optimal choice.

Now consider a different scenario: a titanium aerospace bracket with complex geometry, moderate production volume, and standard tolerances. Material properties and geometric complexity both mandate hot forging, regardless of other preferences.

What about components that fall between these extremes? This is where cold roll forming and hybrid approaches enter the picture. Some applications benefit from warm forging's middle-ground characteristics. Others might use cold forging for precision features followed by localized hot working for complex areas.

According to the University of Strathclyde research, the ideal approach often involves iterative evaluation—reviewing product features and requirements to assess different forging methods with different designs. This redesign loop can reveal opportunities to simplify geometry for cold forging compatibility or optimize material selection to enable preferred processing methods.

When Expert Guidance Makes the Difference

Complex projects often benefit from engineering expertise during method selection. The theoretical framework helps, but experienced forging engineers bring practical knowledge about material behavior, tooling capabilities, and production optimization that transforms good decisions into excellent outcomes.

For automotive applications requiring precision hot forging, manufacturers like Shaoyi (Ningbo) Metal Technology offer in-house engineering support that guides customers through method selection and process optimization. Their rapid prototyping capability—delivering functional samples in as little as 10 days—allows manufacturers to validate forging method choices before committing to production tooling. Combined with their strategic location near Ningbo Port, this enables fast global delivery of both prototype and high-volume production components.

The benefits of forging extend beyond individual component performance. Selecting the optimal method for each application creates cascading advantages: reduced secondary operations, improved material utilization, enhanced mechanical properties, and streamlined production workflows. These cumulative benefits often exceed the value of any single technical improvement.

Making Your Final Decision

As you work through the decision matrix for your specific project, remember that forging methods represent tools in your manufacturing toolkit—not competing philosophies. The goal isn't to champion one approach over another, but to match your unique requirements to the process delivering optimal results.

Start by identifying your non-negotiable requirements. If material properties demand hot forging, that constraint overrides volume preferences. If tolerances must meet precision specifications, cold forging becomes necessary regardless of geometric complexity. These fixed requirements narrow your options before weighted evaluation begins.

Next, assess the flexible factors where trade-offs become possible. Can you simplify geometry to enable cold forging? Would investing in premium tooling justify itself through higher-volume production? Could warm forging's middle-ground characteristics satisfy both tolerance and complexity requirements?

Finally, consider the total cost of ownership—not just per-part forging costs, but secondary operations, quality control, scrap rates, and delivery logistics. The forging method delivering lowest apparent cost may not represent optimal value when downstream factors are included.

Whether you're launching a new product line or optimizing existing production, systematic method selection ensures your forging investment delivers maximum return. The differences between hot and cold forging create distinct advantages for different applications—and understanding these differences empowers you to make decisions that strengthen both your components and your competitive position.

Frequently Asked Questions About Hot and Cold Forging

1. What are the disadvantages of cold forging?

Cold forging has several limitations that manufacturers must consider. The process requires significantly higher press tonnage (500-2000 MPa) compared to hot forging, demanding expensive heavy-duty equipment. Material selection is restricted to ductile metals like low-carbon steel, aluminum, and copper—brittle materials or high-carbon steels above 0.5% carbon will crack under cold forging conditions. Additionally, complex geometries are difficult to achieve since room-temperature metal resists dramatic flow, often requiring multiple forming stages with intermediate annealing treatments that add processing time and cost.

2. What is the advantage of cold forging?

Cold forging delivers exceptional dimensional accuracy (tolerances of ±0.05mm to ±0.25mm), superior surface finishes (Ra 0.4-3.2 μm), and enhanced mechanical properties through work hardening—all without heat treatment. The process achieves up to 95% material utilization compared to 60-80% for hot forging, reducing waste significantly. Cold forged components gain increased tensile strength, improved hardness, and superior fatigue resistance through strain hardening, making them ideal for high-volume precision applications in automotive and industrial manufacturing.

3. Is cold forging stronger than hot forging?

Cold forging produces harder components with higher tensile and yield strength due to work hardening, while hot forging creates parts with superior toughness, ductility, and impact resistance. The choice depends on application requirements—cold forged steel excels in wear-resistant precision components under static loads, whereas hot forged parts perform better under dynamic loading and extreme conditions. Many automotive safety-critical components like crankshafts and suspension arms use hot forging for their refined grain structure and fatigue resistance.

4. What temperature range separates hot forging from cold forging?

The recrystallization temperature serves as the dividing line between these methods. Cold forging occurs at room temperature to approximately 200°C (392°F), while hot forging operates above the recrystallization point—typically 700°C to 1250°C (1292°F to 2282°F) for steel. Warm forging occupies the middle ground at 800°F to 1800°F for steel alloys. Each temperature range produces different material behaviors: hot forging enables complex geometries through continuous recrystallization, while cold forging achieves precision through strain hardening.

5. How do I choose between hot and cold forging for my project?

Evaluate six key factors: part complexity (hot forging for intricate geometries), production volume (cold forging for 100,000+ annual parts), material type (ductile materials favor cold, titanium and high-alloy steels require hot), tolerance requirements (cold for ±0.25mm or tighter), surface finish specifications (cold for Ra < 3.2 μm), and budget constraints (cold requires higher tooling investment but lower per-part costs). Companies like Shaoyi offer rapid prototyping in as little as 10 days to validate method selection before committing to production tooling.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —