Hydraulic vs Mechanical Press for Stamping: Speed, Force & Cost

TL;DR

Choosing between a hydraulic and a mechanical press comes down to a trade-off between speed and force control. Mechanical presses are the industry workhorses for high-volume production, using stored flywheel energy to deliver rapid, consistent cycles ideal for blanking and shallow forming. Hydraulic presses, conversely, generate force via fluid pressure, delivering full rated tonnage throughout the entire stroke—making them superior for deep drawing, complex shapes, and variable production runs. For manufacturers balancing these needs, understanding the specific mechanics of force application is the first step to optimizing production cost and quality.

The Core Difference: Flywheel Energy vs. Fluid Pressure

The fundamental distinction lies in how each machine generates and delivers force. This engineering difference dictates every aspect of their performance, from cycle time to maintenance.

Mechanical presses operate on kinetic energy. An electric motor accelerates a massive flywheel, which stores energy. When the operator engages the clutch, this energy is released through a gear and crank system to drive the ram. The motion is fixed and cyclical—like a hammer strike. This design allows for incredible speed and repeatability but offers little flexibility in terms of stroke profile.

Hydraulic presses rely on hydrostatic pressure. A pump forces hydraulic fluid into a cylinder, pushing a piston down. The force is generated by the applied pressure of the fluid, not the momentum of a moving mass. This creates a pushing motion closer to a vise squeeze than a hammer blow. The ram allows for variable speed and position control, enabling the operator to manage exactly how and when force is applied to the workpiece.

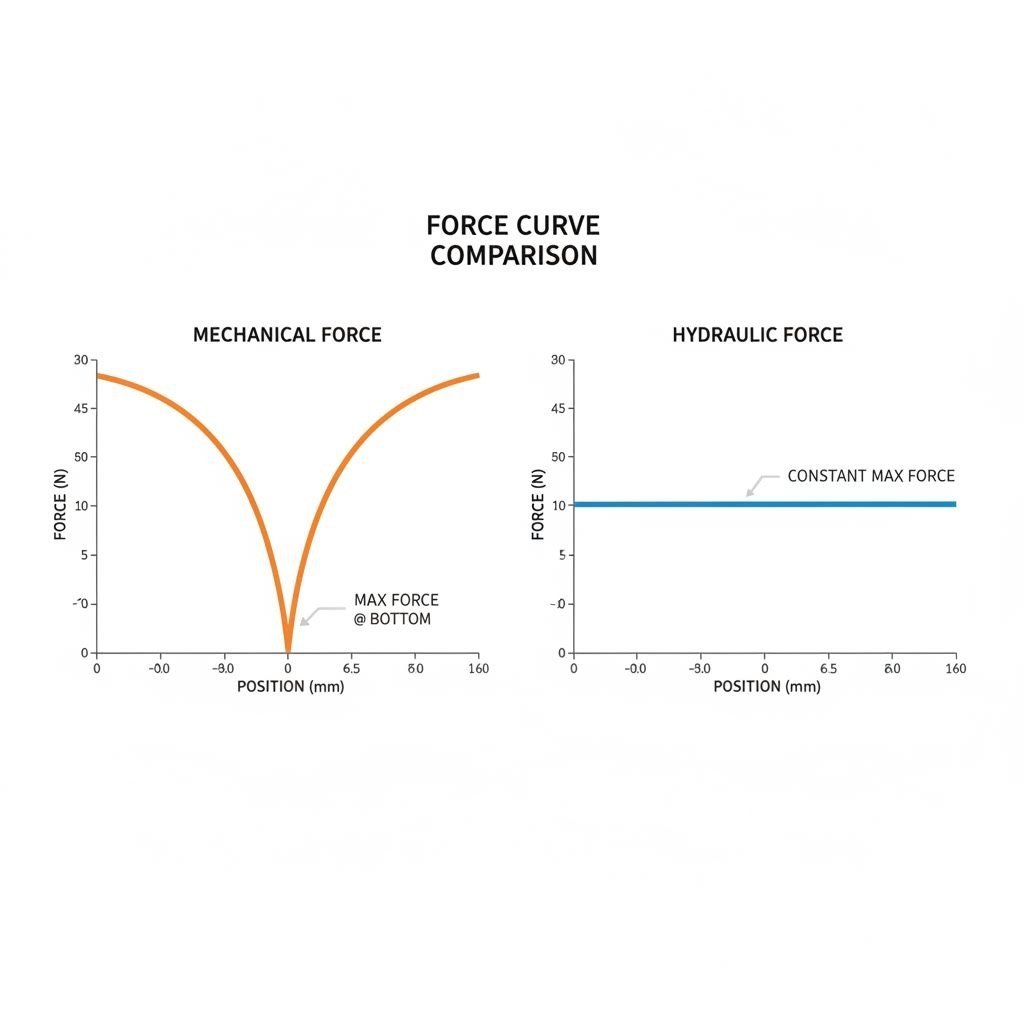

Tonnage and Force Application: The Critical Curve

The most significant technical differentiator for engineers is where in the stroke the press can deliver its rated tonnage. This factor often determines whether a press can physically perform a specific job.

Mechanical: Rated at Bottom Dead Center (BDC)

A mechanical press is rated for its maximum tonnage only at the very bottom of its stroke, known as Bottom Dead Center (BDC). As the ram is higher up in the stroke, the available force is significantly lower due to the mechanical advantage curve of the crank/eccentric drive. For example, a 200-ton mechanical press might only deliver 50 tons of force two inches above the bottom. This limitation makes mechanical presses poor candidates for deep drawing applications where high force is needed early in the stroke.

Hydraulic: Full Tonnage Anywhere

In contrast, a hydraulic press can deliver its full rated force at any point in the stroke. Whether the ram is at the top, middle, or bottom, the hydraulic system can apply maximum pressure instantly. This characteristic is critical for deep drawing operations, where the material requires consistent forming pressure over a long distance to flow correctly without tearing.

Speed, Production Volume, and Efficiency

Speed is often the primary cost driver in metal stamping, and this is where mechanical presses historically dominate.

- High-Volume Speed: Mechanical presses are built for speed. Small gap-frame mechanical presses can achieve speeds up to 1,500 strokes per minute (SPM), while larger straight-side presses still run significantly faster than comparable hydraulics. For parts like electrical connectors, washers, or automotive brackets requiring millions of units, the fixed cycle of a mechanical press is unbeatable.

- Low-Volume Versatility: Hydraulic presses are inherently slower due to the time required to pump fluid. However, they excel in high-mix, low-volume environments. Their setup time is typically faster because stroke limits are programmable rather than mechanical. They are also ideal for trial runs and prototyping.

For manufacturers scaling up, the transition often moves from hydraulic flexibility to mechanical speed. Specialized partners like Shaoyi Metal Technology leverage this progression, utilizing diverse press capabilities to support automotive clients from initial low-volume prototyping up to mass production of millions of IATF 16949-certified components.

Design Flexibility, Setup, and Maintenance

Beyond the raw performance specs, the daily operational reality of these machines differs significantly.

| Feature | Mechanical Press | Hydraulic Press |

|---|---|---|

| Stroke Control | Fixed stroke length (rigid) | Fully adjustable stroke length |

| Overload Safety | Risk of locking up at BDC (costly fix) | Built-in relief valves (safe overload) |

| Maintenance | Clutch/brake wear, lubrication points | Seals, hoses, pumps (leak potential) |

| Die Setup | Precise shut height critical | Forgiving shut height (flexible) |

Safety and Overload: A major advantage of hydraulic systems is overload protection. If a hydraulic press exceeds its tonnage limit, a relief valve simply opens, and the pressure bleeds off harmlessly. A mechanical press, however, can become "stuck on bottom" if overloaded at BDC, often requiring hours of maintenance to free the ram and potentially damaging expensive tooling.

Maintenance Realities: Mechanical presses are robust and can last decades with proper lubrication, though clutch and brake linings are wear items. Hydraulic presses have fewer moving hard parts but require vigilance regarding fluid cleanliness, seal integrity, and hose condition to prevent leaks and pressure drops.

The Servo Press: The Modern Hybrid

In recent years, servo press technology has emerged to bridge the gap. A servo press uses a high-torque servo motor to drive a mechanical linkage, eliminating the flywheel and clutch. This allows for fully programmable stroke profiles—users can program the ram to slow down during the forming portion of the stroke (to reduce heat and improve part quality) and speed up during the return stroke.

While servo presses offer the "best of both worlds"—the speed of mechanical with the controllability of hydraulic—they come with a higher initial capital cost. They are increasingly the standard for high-precision industries like EV battery component manufacturing where complex forming curves are required alongside high throughput.

Summary: Which Press is Right for You?

Selecting the right press is not about finding the "better" technology, but matching the machine to your specific production reality. Use this framework to guide your decision:

- Choose a Mechanical Press if: You are running high-volume production (thousands to millions of parts), your parts are relatively flat (blanking, piercing, shallow forming), and speed is your number one priority.

- Choose a Hydraulic Press if: You need to perform deep draws, your production involves a high mix of different parts with frequent changeovers, or you need full tonnage capacity throughout a long stroke.

- Choose a Servo Press if: You require the precision to control material flow in complex parts, need energy efficiency, and have the budget to invest in versatile, future-proof technology.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Can a hydraulic press do blanking operations?

Yes, hydraulic presses can perform blanking, but they are generally less efficient at it than mechanical presses. The "snap-through" shock generated when the material fractures can be damaging to the hydraulic system over time unless the press is equipped with specialized dampening shocks. For pure blanking operations, mechanical presses are typically preferred due to their speed and rigidity.

2. Why is a mechanical press faster than a hydraulic press?

A mechanical press is faster because it utilizes energy stored in a continuously rotating flywheel. When the clutch engages, this stored kinetic energy is released almost instantly to drive the ram. A hydraulic press must pump fluid to generate force for every single cycle, which is an inherently slower process involving valve shifts and pressure build-up.

3. Which press type is safer for the operator and tooling?

Hydraulic presses are generally considered safer for tooling regarding overloads. If a foreign object enters the die or the material is too thick, the hydraulic system's relief valve will trip, stopping the press immediately without damage. A mechanical press will attempt to complete its rigid cycle regardless of obstruction, which can result in catastrophic damage to the die or the press structure itself.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —