Aluminum Automotive Stamping Process: Alloys, Springback & Defects

TL;DR

The aluminum automotive stamping process is a critical lightweighting strategy that reduces vehicle mass by up to 40–60% compared to traditional steel construction. This fabrication method involves transforming aluminum alloy sheets—primarily 5xxx (Al-Mg) and 6xxx (Al-Mg-Si) series—into complex structural and skin components using high-tonnage presses and precision dies. However, aluminum presents unique engineering challenges, including a Young’s Modulus only one-third that of steel, which leads to significant springback, and an abrasive oxide layer that demands advanced tribology solutions. Successful execution requires specialized servo press kinematics, warm forming techniques, and strict adherence to design guidelines like limiting draw ratios (LDR) to below 1.6.

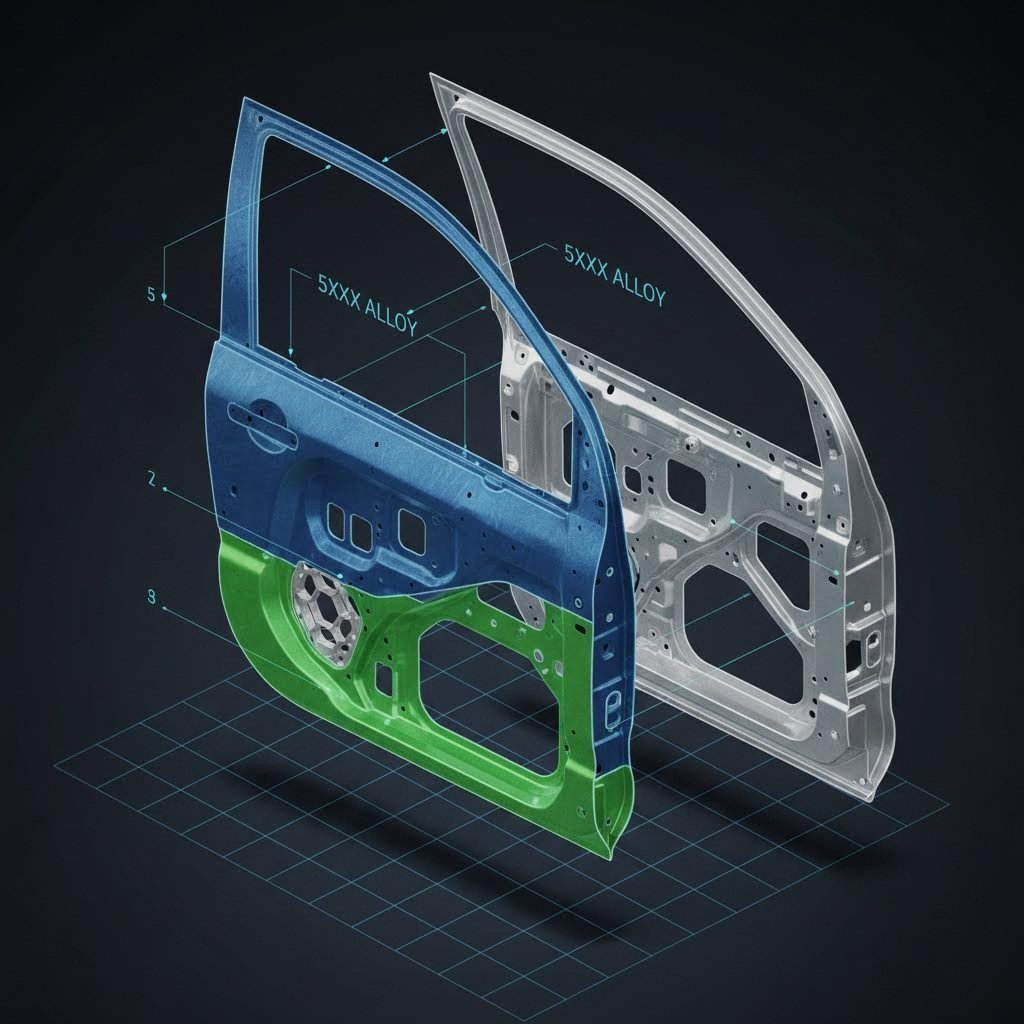

Automotive Aluminum Alloys: 5xxx vs. 6xxx Series

Selecting the correct alloy is the foundational step in the aluminum automotive stamping process. Unlike steel, where grades are often interchangeable with minor process adjustments, aluminum alloys possess distinct metallurgical behaviors that dictate their application in the Body-in-White (BiW).

5xxx Series (Aluminum-Magnesium)

The 5xxx series alloys, such as 5052 and 5083, are non-heat treatable and gain strength solely through strain hardening (cold working). They offer excellent formability and high corrosion resistance, making them ideal for complex inner structural parts, fuel tanks, and chassis components. However, engineers must be wary of "Lüders lines" (stretcher strains)—unsightly surface markings that occur during yielding. Because of this, 5xxx alloys are typically restricted to non-visible inner panels where surface aesthetics are secondary to structural integrity.

6xxx Series (Aluminum-Magnesium-Silicon)

The 6xxx series, including 6061 and 6063, is the standard for exterior "Class A" surface panels like hoods, doors, and roofs. These alloys are heat treatable. They are typically stamped in a T4 temper (solution heat-treated and naturally aged) to maximize formability, then artificially aged to T6 temper during the paint bake cycle (bake hardening). This process significantly increases yield strength, providing the dent resistance required for outer skin panels. The trade-off is a stricter forming window compared to 5xxx grades.

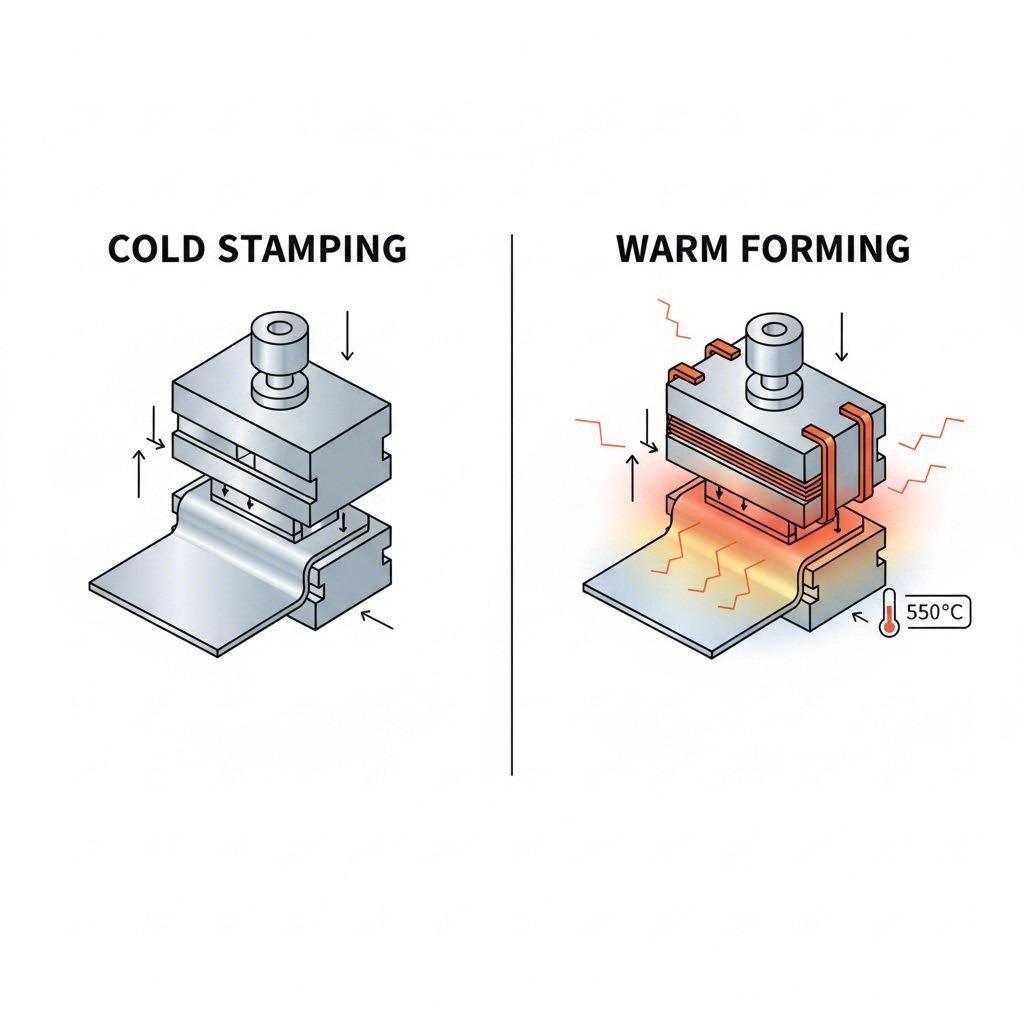

The Stamping Process: Cold vs. Warm Forming

Forming aluminum requires a fundamental shift in mindset from steel stamping. MetalForming Magazine notes that medium-strength aluminum has roughly 60% of the stretching ability of steel. To overcome this, manufacturers employ two primary processing strategies.

Cold Stamping with Servo Technology

Standard cold stamping is effective for shallower parts but requires precise control over ram speed. Servo presses are essential here; they allow operators to program "pulse" or "pendulum" motions that reduce impact speed and dwell at the bottom of the stroke (BDC). This dwell time reduces springback by allowing the material to relax before the tooling retracts. Cold forming relies heavily on compressive forces rather than tensile stretching. A helpful analogy is a tube of toothpaste: you can shape it by squeezing (compression), but pulling it (tension) causes immediate failure.

Warm Forming (Elevated Temperature Forming)

For complex geometries where cold formability is insufficient, warm forming is the industry solution. By heating the aluminum blank to temperatures typically between 200°C and 350°C, manufacturers can increase elongation by up to 300%. This reduces the flow stress and allows for deeper draws and sharper radii that would split at room temperature. However, warm forming introduces complexity: dies must be heated and insulated, and cycle times are slower (10–20 seconds) compared to cold stamping, impacting the cost-per-part equation.

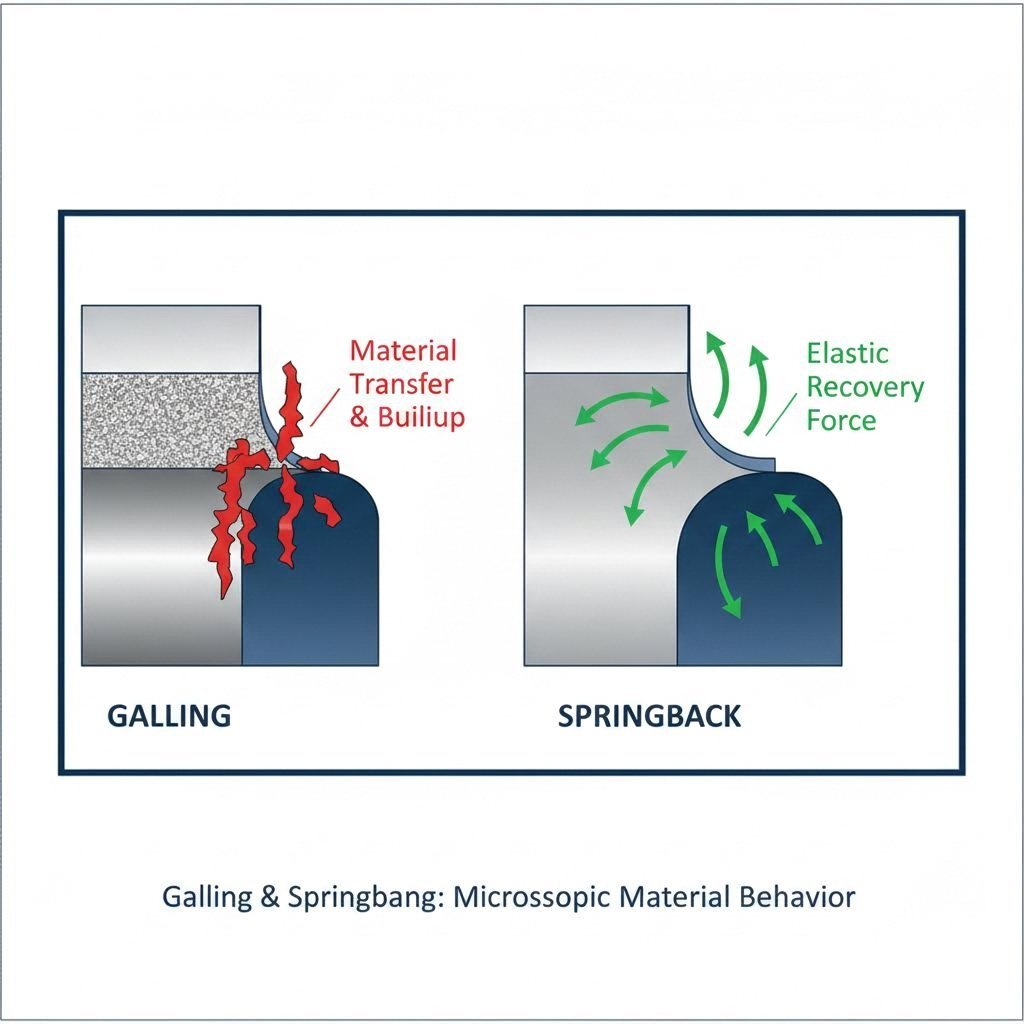

Critical Challenges: Springback & Surface Defects

The aluminum automotive stamping process is defined by its battle against elastic recovery and surface imperfections. Understanding these failure modes is crucial for process design.

- Springback Severity: Aluminum has a Young’s Modulus of approximately 70 GPa, compared to steel’s 210 GPa. This means aluminum is three times more "springy," leading to significant dimensional deviations after the die opens. Compensation requires sophisticated simulation software (like AutoForm) to over-crown the die surfaces and the use of post-form restriking operations to lock in geometry.

- Galling and Aluminum Oxide: Aluminum sheets are covered in a hard, abrasive aluminum oxide layer. During stamping, this oxide can break off and adhere to the tool steel—a phenomenon known as galling. This buildup scratches subsequent parts and degrades tool life rapidly.

- Orange Peel: If the grain size of the aluminum sheet is too coarse, the surface can roughen during forming, resembling the skin of an orange. This defect is unacceptable for Class A exterior surfaces and requires strict metallurgical control from the material supplier.

Tooling & Tribology: Coatings and Lubrication

To mitigate galling and ensure consistent quality, the tooling ecosystem must be optimized specifically for aluminum. Standard uncoated tool steels are insufficient. Punches and dies typically require Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD) coatings, such as Diamond-Like Carbon (DLC) or Chromium Nitride (CrN). These coatings provide a hard, low-friction barrier that prevents the aluminum oxide from adhering to the tool steel.

Lubrication strategy is equally vital. Traditional wet oils often fail under the high contact pressures of aluminum stamping or interfere with downstream welding and bonding. The industry has shifted toward Dry Film Lubricants (hot melts) applied to the coil at the mill. These lubricants are solid at room temperature—improving housekeeping and reducing "wash-off"—but liquefy under the heat and pressure of forming to provide superior hydrodynamic lubrication.

For OEMs and Tier 1 suppliers moving from prototyping to mass production, validating these tooling strategies early is essential. Partners like Shaoyi Metal Technology specialize in bridging this gap, offering engineering support and high-tonnage capabilities (up to 600 tons) to refine tribology and geometry before full-scale launch.

Design Guidelines for Aluminum Stamping

Product engineers must adapt their designs to aluminum’s limitations. Direct substitution of steel geometry will likely result in splitting or wrinkling. The following heuristics are widely accepted for ensuring manufacturability:

| Feature | Steel Guideline | Aluminum Guideline |

|---|---|---|

| Limiting Draw Ratio (LDR) | Up to 2.0 - 2.2 | Max 1.6 (requires intermediate annealing for deeper draws) |

| Punch Radii | 3-5x Material Thickness (t) | 8-10x Material Thickness (t) |

| Die Radii | 3-5x t | 5-10x t (Must be smaller than punch radius) |

| Wall Angle | Near vertical possible | Draft angles required to facilitate material flow |

Furthermore, designers should utilize "addendum" features—geometry added outside the final part line—to control material flow. Draw beads and lock beads are essential to restrain the metal and stretch it sufficiently to prevent wrinkling, especially in low-curvature areas like door panels.

Conclusion

Mastering the aluminum automotive stamping process requires a convergence of metallurgy, advanced simulation, and precise tribology. While the transition from steel demands stricter process windows and higher tooling investments, the payoff in vehicle lightweighting and fuel efficiency is undeniable. By respecting the unique properties of 5xxx and 6xxx alloys—specifically their lower modulus and limiting draw ratios—manufacturers can produce high-integrity components that meet the rigorous standards of the modern automotive industry.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the difference between cold and warm aluminum stamping?

Cold stamping is performed at room temperature and uses servo press kinematics to manage material flow, suitable for simpler parts. Warm stamping involves heating the aluminum blank to 200°C–350°C, which increases the material's elongation by up to 300%, enabling the formation of complex geometries that would split under cold forming conditions.

2. Why is springback worse in aluminum than in steel?

Springback is governed by the material's Young’s Modulus (stiffness). Aluminum has a Young’s Modulus of about 70 GPa, which is roughly one-third that of steel (210 GPa). This lower stiffness causes aluminum to elastic recover (spring back) significantly more when the forming pressure is released, requiring advanced die compensation strategies.

3. Can standard steel stamping dies be used for aluminum?

No. Aluminum stamping dies require different clearances (typically 10–15% of material thickness) and significantly larger radii (8–10x thickness) to prevent cracking. Additionally, tooling for aluminum often requires specialized DLC (Diamond-Like Carbon) coatings to prevent galling caused by aluminum's abrasive oxide layer.

4. What is the "Limiting Draw Ratio" for aluminum?

The Limiting Draw Ratio (LDR) for aluminum alloys is typically around 1.6, meaning the blank diameter should not exceed 1.6 times the punch diameter in a single draw. This is significantly lower than steel, which can withstand LDRs of 2.0 or higher, necessitating more conservative process designs or multiple draw steps for aluminum.

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —

Small batches, high standards. Our rapid prototyping service makes validation faster and easier —