Основни принципи за проектиране на ковани изделия

Накратко

Проектирането на детайл за осъществимост на производство чрез коване изисква стратегическо планиране на геометрията му, за да се улесни процесът на метално коване. Това включва внимателен контрол на ключови елементи като линията на разделяне, ъгли на наклона, радиуси на ъглите и дебелина на стените, за да се осигури гладко течение на материала, да се предотвратят дефекти и да се позволи лесно изваждане на детайла от матрицата. Правилният дизайн минимизира разходите, намалява последващата обработка и максимизира вродената якост на кованата компонента.

Основи на проектирането за осъществимост на производство чрез коване (DFM)

Проектиране за технологичност при коване (DFM) е специализирана инженерна практика, насочена към оптимизиране на конструкцията на детайл за процеса на коване. Основната цел е създаването на компоненти, които не само изпълняват функцията си, но и са ефективни и икономически изгодни за производство. Като се имат предвид ограниченията и възможностите на процеса на коване от самото начало, инженерите могат значително да намалят производствените разходи, да подобрят качеството на крайния продукт и да минимизират нуждата от обширни вторични операции като механична обработка. Както посочват експертите, коването подравнява зърнестия поток на метала с формата на детайла, което подобрява механичните свойства като устойчивост на умора и ударна якост. Този процес произвежда компоненти с превъзходна якост и дълготрайност в сравнение с леене или механична обработка .

Основните цели на DFM за коване включват:

- Намаляване на сложността: Прости, симетрични форми се коват по-лесно, изискват по-малко сложни шаблони и водят до по-малко дефекти.

- Осигуряване на течението на материала: Конструкцията трябва да позволява на метала да се движи гладко и напълно да запълва кухината на матрицата, без да създава празноти или застъпвания.

- Стандартизиране на компоненти: Където е възможно, използването на стандартни размери и характеристики може да намали разходите за инструменти и производственото време.

- Минимизиране на отпадъците: Оптимизирането на първоначалния размер на заготовката и геометрията на детайла намалява материалните отпадъци, по-специално „преливащия материал“ (флаш), който се отстранява след коването.

Игнорирането на тези принципи може да доведе до значителни предизвикателства. Лоши проектиращи решения могат да доведат до производствени дефекти, увеличен износ на инструменти, по-големи материални загуби и в крайна сметка до по-слаб и по-скъп крайни продукт. За компании в изискващи сектори като автомобилната и аерокосмическата промишленост, партньорството с компетентен производител е от решаващо значение. Например, специалисти в горещото коване за автомобилна промишленост, като Shaoyi Metal Technology , използват своя опит в производството на матрици и производствени процеси, за да гарантират, че конструкцията е оптимизирана както за производителност, така и за ефективност – от прототипиране до масово производство.

Основно геометрично съображение 1: Линията на разделяне и ъглите на извличане

Сред най-важните елементи при проектирането на коване са разделителната линия и ъглите на наклона. Тези характеристики пряко влияят върху сложността на матрицата, потока на материала и лекотата, с която готовата част може да бъде извадена от инструменталната екипировка. Добре планираният подход към тези аспекти е от основно значение за успешната и ефективна операция по коване.

Линията на разделяне

Линията на разделяне е повърхнината, където се срещат двете половини на ковашката матрица. Нейното местоположение е важно решение в процеса на проектиране и трябва ясно да бъде посочено на всеки чертеж на ковано изделие. Идеално линията на разделяне трябва да лежи в една равнина и да бъде позиционирана около най-голямата проектирана площ на детайла. Това помага да се осигури балансирано течение на материала и минимизира силите, необходими за коването на компонента. Според препоръки от Engineers Edge , правилно поставената разделяща линия също помага за контролиране на посоката на зърнения поток и предотвратява подрязвания, които биха направили невъзможно изваждането на детайла от матрицата.

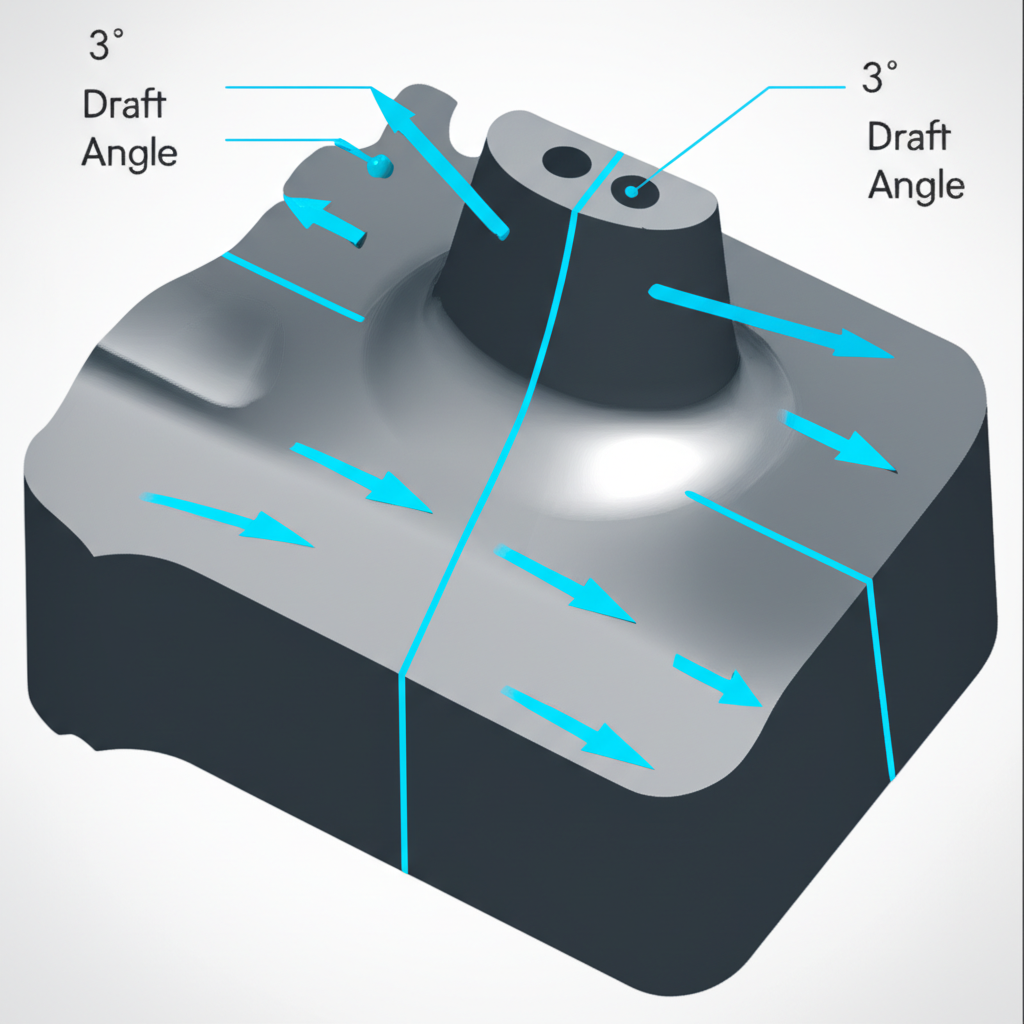

Ъгли на извличане

Ъглите на наклона са малки конусности, приложени към всички вертикални повърхности на кованата част, които са успоредни на движението на матрицата. Основната им цел е да улеснят лесното премахване на детайла от матрицата след формирането му. При липса на достатъчен наклон, детайлът може да заседне, което води до повреди както на самия компонент, така и на скъпата матрица. Необходимият ъгъл на наклона зависи от сложността на детайла и материала, който се кове, но типичните ъгли на наклона за стоманени ковани детайли варират между 3 и 7 градуса . Недостатъчният наклон може да причини дефекти, увеличава износването на матрицата и забавя производствения цикъл.

Основно геометрично съображение 2: Ребра, фланци и радиуси

Освен от общата форма, проектирането на конкретни елементи като ребра, стени и радиуси на ъгли и заобления е от съществено значение за възможността за производство. Тези елементи трябва да бъдат проектирани така, че да осигуряват гладко течение на материала и да предотвратяват чести дефекти при коване, като в същото време гарантират структурната цялост на крайния компонент.

Ребра и стени

Ребрата са тесни издадени елементи, често използвани за увеличаване на якостта и огъваемостта на детайл, без да се добавя излишно тегло. Стените са тънките участъци материал, свързващи ребрата и други елементи. При проектирането им е от решаващо значение да се контролират техните пропорции. Високи и тесни ребра могат да бъдат трудни за запълване с материал, което води до дефекти. Общото правило е височината на ребро да не надвишава шест пъти неговата дебелина. Освен това, дебелината на реброто идеално трябва да бъде равна или по-малка от дебелината на стената, за да се предотвратят проблеми при обработката.

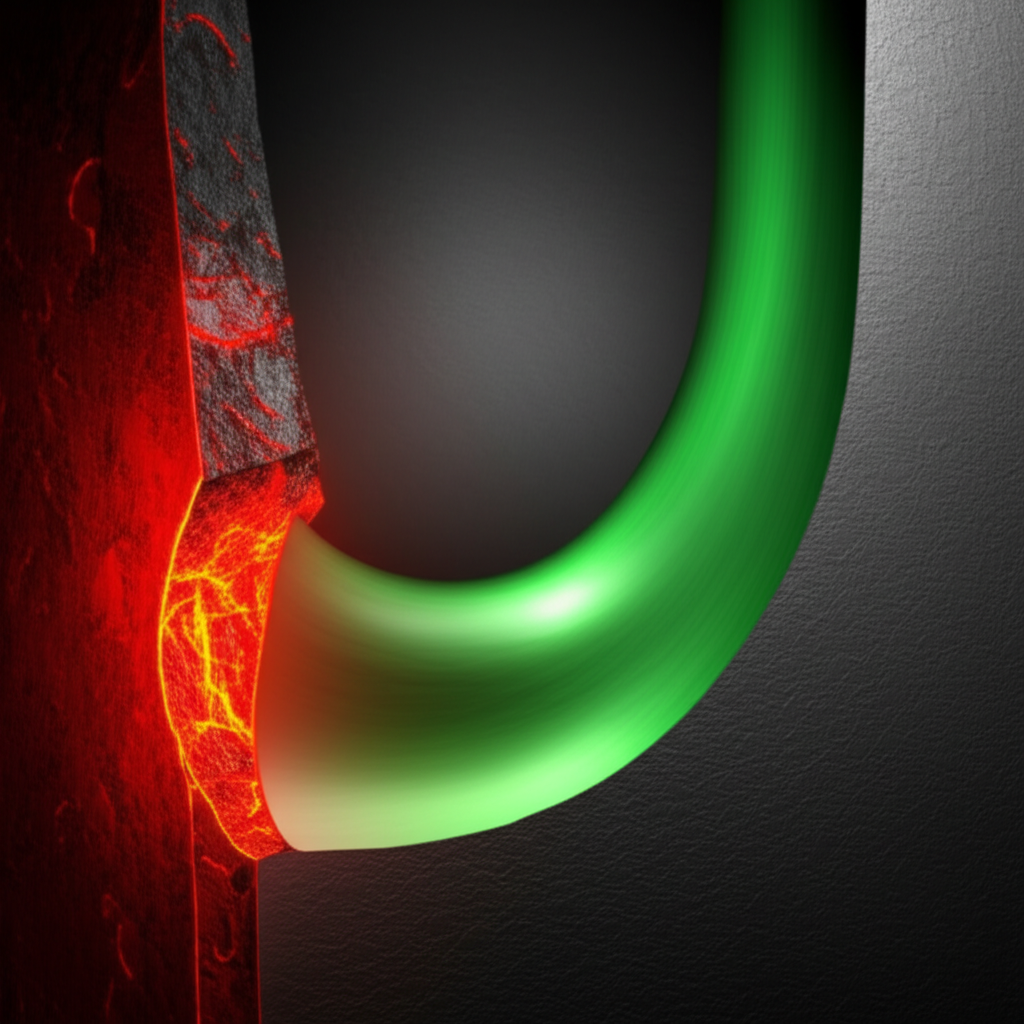

Радиуси на ъгли и заобления

Едно от най-важните правила при проектирането на коване е да се избягват рязко изразени вътрешни и външни ъгли. Остри ъгли затрудняват течението на метала, което води до дефекти като надви и студени затваряния, при които материала се прегъва върху себе си. Те също създават концентрации на напрежение както в матрицата, така и в крайната детайл, което може да намали уморния живот. Използването на достатъчно големи радиуси на закръгления (вътрешни) и ъгли (външни) е задължително. Тези заоблени ръбове помагат на метала да тече гладко във всички части на полостта на матрицата, осигуряват пълно запълване и разпределят напрежението по-равномерно. Това не само подобрява якостта на детайла, но и удължава живота на ковашките матрици, като намалява износването и риска от пукане.

Управление на течението на материала: дебелина на сечението и симетрия

Основната физика на коването включва принудително деформиране на твърд метал, като се задвижва той да се движи като гъста течност в желаната форма. Следователно контролът върху този материален поток е от първостепенно значение за получаването на бездефектна детайл. Ключов момент е запазването на еднаква дебелина на стените и използването на симетрия, когато е възможно.

Резките промени в дебелината на стените могат да причинят сериозни проблеми. Металът винаги следва пътя на най-малко съпротивление, а изведнъж преход от дебела към тънка секция може да ограничи потока, поради което тънката част не се запълва напълно. Това също може да доведе до топлинни градиенти по време на охлаждане, което предизвиква деформации или пукнатини. Идеалният дизайн за коване поддържа еднородна дебелина на стените по цялата част. Когато промените са неизбежни, те трябва да бъдат постепенни, с гладки, конични преходи. Това гарантира равномерно разпределение на налягането и еднороден поток на метала във всички области на матрицата.

Симетрията е друго мощно средство за дизайнера. Симетричните части по принцип са по-лесни за коване, тъй като осигуряват балансирано течение на материала и опростяват конструкцията на матриците. Силите се разпределят по-равномерно и детайлът е по-малко податлив на деформации по време на коването и последващото охлаждане. Когато приложението го позволява, проектирането на прости, симетрични форми почти винаги ще доведе до по-издръжлив, икономически изгоден производствен процес и до крайов компонент с по-високо качество.

Планиране на следобработката: Машинни допуски и толеранси

Въпреки че коването може да произвежда детайли, които са много близки до окончателната си форма (близки до нетна форма), често се изисква вторична механична обработка, за да се постигнат стегнати толеранси, определени повърхностни финишни обработки или елементи, които не могат да бъдат ковани. Важна част от проектирането с оглед възможността за производство е планирането за тези стъпки на следобработка още от самото начало.

„Машинна обработка“ е допълнителен материал, преднамерено добавен към кованата повърхност, която по-късно ще бъде механично обработвана. Това гарантира достатъчно количество материал за премахване, за да се постигне окончателният точен размер. Типичното допускане за машинна обработка може да бъде около 0,06 инча (1,5 мм) за всяка повърхност, но това може да варира в зависимост от размера и сложността на детайла. При проектирането трябва да се има предвид натрупването на най-лошия случай на допуски и ъглите на извличане при определяне на това допускане.

Допуснатите отклонения при коване естествено са по-широки, отколкото при прецизната механична обработка. Задаването на реалистични допуски за суровата кована детайл е от решаващо значение за контрола върху разходите. Опитът да се задържат ненужно тесни допуски при коване може значително да увеличи разходите за инструменти и процента на брак. Вместо това проектът трябва да прави разлика между критични повърхнини, които ще се механично обработват, и некритични повърхнини, които могат да останат в ковано състояние. Като изясни ясно тези изисквания на чертежа, проектиращият може да създаде детайл, който е едновременно функционален и икономически изгоден за производство, като така съчетае суровото коване с готовия компонент.

Често задавани въпроси

1. Какви са конструктивните съображения при коване?

Основните аспекти при проектирането на коване включват избора на подходящ материал, определяне на геометрията на детайла за осигуряване на добро течение на метала и задаване на ключови характеристики. Те включват местоположението на разделящата линия, достатъчни ъгли на усукване за изваждане на детайла, достатъчно големи радиуси на заобления и ъгли, за да се избегнат концентрации на напрежение, както и поддържане на еднородна дебелина на стените. Освен това конструкторите трябва да предвидят допуски за механична обработка и реалистични допуски за последващи операции след коването.

2. Как се проектира детайл за производство?

Проектирането на детайл за производство (DFM) включва опростяване на конструкцията, за да се намали сложността и цената. Основните принципи са намаляване на общия брой части, използване на стандартни компоненти, когато е възможно, проектиране на многфункционални части и избор на материали, които са лесни за обработка. Конкретно при коване това означава проектиране за равномерно течение на материала, избягване на остри ъгли и минимизиране на нуждата от вторични операции.

3. Какво характеризира проектирането за производимост?

Проектирането за производимост (DFM) се характеризира с превантивен подход, при който производственият процес се взема предвид още в ранната фаза на проектирането. Основните му принципи включват оптимизиране на проекта за по-лесно изработване, икономическа ефективност и качество. Това означава фокус върху елементи като избор на материали, възможности на процеса, стандартизиране и намаляване на сложността, за да се гарантира, че крайният продукт може да бъде произведен надеждно и ефективно.

Малки порции, високи стандарти. Нашата услуга за бързо проектиране на прототипи прави валидацията по-бърза и лесна —

Малки порции, високи стандарти. Нашата услуга за бързо проектиране на прототипи прави валидацията по-бърза и лесна —