Mit kell tudni a kovácsolás és az extrudálás közötti különbségekről

A fémalakítás alapjainak megértése

Ha kritikus alkalmazásra szerez be alkatrészeket, a gyártási eljárás, amelyet választ, meghatározhatja a termék teljesítményét. Bonyolultnak hangzik? Nem kell, hogy az legyen. Legyen Ön mérnök, aki alkatrészeket specifikál, beszerzési szakember, aki beszállítókat értékel, vagy gyártó, aki a termelést optimalizálja, a fémek alakításának ismerete segíti Önt jobb döntések meghozatalában.

A fémalakítás során nyers anyagból irányított képlékeny alakváltoztatással készülnek funkcionális alkatrészek. A leggyakrabban használt módszerek közé tartozik a kovácsolás és a sajtolás. Mindkettő olyan eljárás, amelynél a fém olvasztása nélkül történik az alakítás, mégis eltérő mechanizmusokon keresztül működnek, amelyek nagyon különböző eredményekhez vezetnek.

Miért befolyásolja a fémalakítási módszer kiválasztása a termék teljesítményét

Képzelje el, hogy egy olyan felfüggesztési alkatrészt kell megadnia, amely terhelés alatt meghibásodik, vagy egy olyan alumíniumprofil, amely a szerelés során eltörik. Ezek a hibák gyakran egyetlen alapvető okra vezethetők vissza: a helytelen alakítási eljárás kiválasztására. A nyomásos öntés és a kovácsolás közötti különbség, illetve az extrudálás választása a kovácsolással szemben nem csupán költségkérdés. Közvetlen hatással van az anyag szilárdságára, tartósságára és megbízhatóságára.

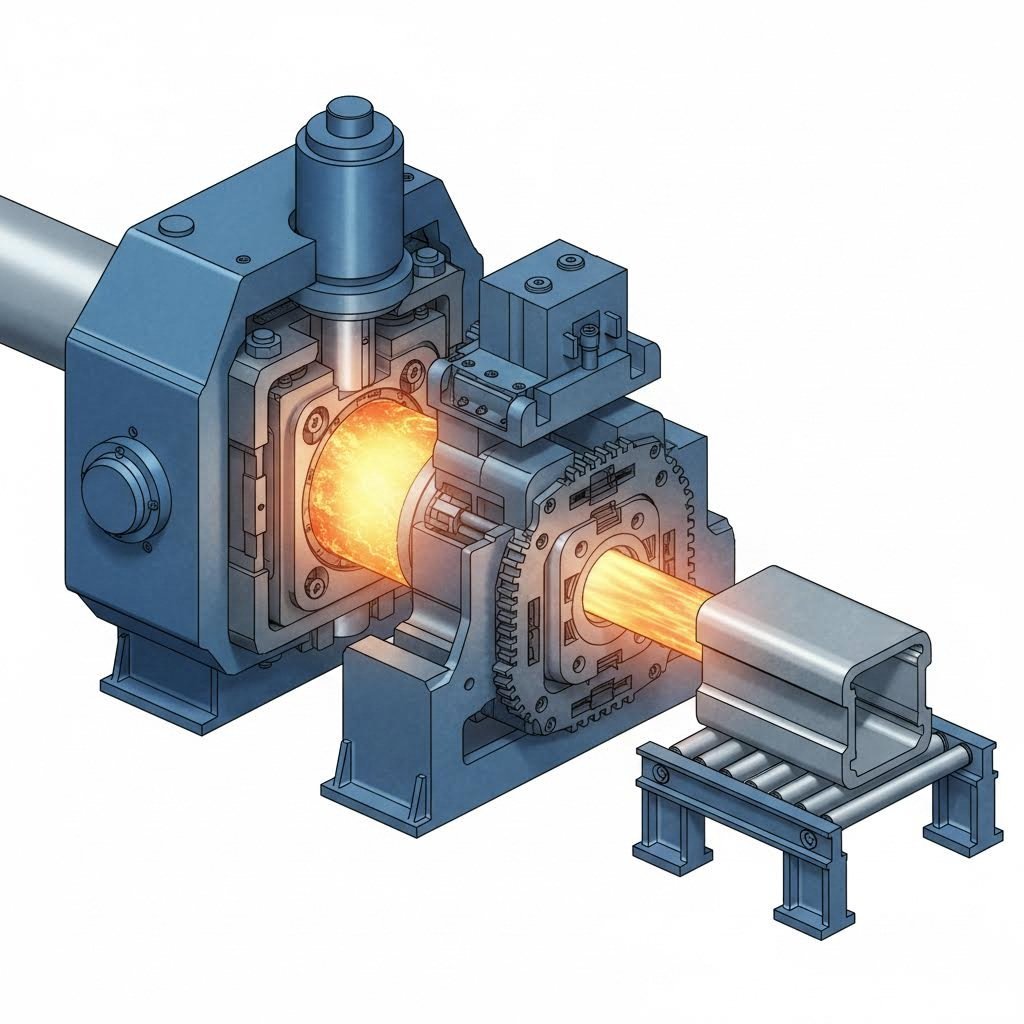

Mi is az extrudálás, és hogyan különbözik a kovácsolástól? A kovácsolás olyan gyártási eljárás, amely során a fémeket nyomóerővel formázzák, általában kalapáccsal, sajtolóval vagy forma segítségével. A fémeket általában alakítható hőmérsékletre hevítik, vagy szobahőmérsékleten dolgozzák fel, majd ütéssel vagy nyomással alakítják át. Az extrudálás másrészről forró vagy szobahőmérsékletű tömbök nyomásos áthajtását jelenti pontos formák (kések)on keresztül, így folyamatos, állandó keresztmetszetű profilokat hozva létre.

A nyomó- és folyamatos alakítás közötti alapvető különbség

Gondolja így: a kovácsolás olyan, mint egy szobrász, aki agyaggal dolgozik, több irányból alkalmazott erővel sűríti és formálja az anyagot. Az extrudálás inkább úgy működik, mint a fogkrém kinyomása a tubusból, amikor anyagot préselnek át egy formázott nyíláson, hogy folyamatos, egységes keresztmetszetet hozzanak létre.

Az erőalkalmazás ezen alapvető különbsége teljesen eltérő eredményekhez vezet. Amikor öntést hasonlítunk össze kovácsolással, vagy az öntést és kovácsolást az extrudálással értékeljük, látható, hogy az egyes formázási módszerek különleges előnyökkel rendelkeznek az alkalmazási igényektől függően.

Ez az útmutató világos keretrendszert ad ezeknek az eljárásoknak az értékeléséhez. A következő három kulcsfontosságú tényező különbözteti meg a kovácsolást az extrudálástól:

- Erőalkalmazás módja: A kovácsolás kalapácsok vagy sajtok segítségével kifejtett nyomóerőt használ a fém háromdimenziós átalakítására, míg az extrudálás anyagot nyom át egy sablonon (dúcön), hogy kétdimenziós keresztmetszeti profilokat hozzon létre.

- Eredményként kapott szemcseszerkezet: A kovácsolás az anyagbelső szemcsestruktúrát igazítja és finomítja, így biztosítva kiváló irányított szilárdságot, míg az extrudálás a kinyomás irányával párhuzamos szemcseirányultságot hoz létre, eltérő mechanikai tulajdonságokkal.

- Geometriai lehetőségek: A kovácsolás kiválóan alkalmas összetett háromdimenziós alakzatok és zárt üregek előállítására, míg az extrudálás folyamatos, állandó keresztmetszetű profilokat hoz létre, amelyek ideálisak csövek, rúdok és bonyolult lineáris formák gyártásához.

A cikk végére pontosan megérti, hogy mikor melyik eljárás nyújtja a legjobb eredményt, és hogyan illessze össze alkatrész-igényeit a legmegfelelőbb gyártási módszerrel.

A kovácsolás folyamata

Most, hogy megértette a fémalakító eljárások alapvető különbségeit, mélyebben is belemerülhetünk abba, hogyan is működik valójában a kovácsolás. Amikor egy nagy teljesítményű alkalmazásban kovácsolt alumínium alkatrészt lát, olyan fémről van szó, amely molekuláris szinten alapvetően átalakult. Ez az átalakulás adja a kovácsolt alkatrészek híres erősségét és tartósságát.

Hogyan alakítják át a nyomóerők a fém rudakat

Képzeljen el egy fémrudat, amely két bélyeg között helyezkedik el. Amikor hatalmas nyomóerőt alkalmaznak, valami figyelemre méltó történik. A fém nemcsak megváltoztatja az alakját; belső szerkezete teljesen újrarendeződik. Az űrtartás során a fém munkadarabokat szabályozott alakváltozásnak vetik alá, amely újraelosztja és finomítja az anyag szemcseszerkezetét.

Két fő módszer létezik ennek az átalakulásnak az elérésére:

Melegkovácsolás: A fém munkadarabot általában 700 °C és 1200 °C közötti hőmérsékletre hevítik, így rendkívül alakíthatóvá válik. A gyártástechnológiai kutatások szerint ez a magas hőmérséklet csökkenti az anyag folyáshatárát, miközben növeli a szívósságát, lehetővé téve a könnyebb alakváltozást és szemcseirányítást. Az alumínium űrtartás például pontos hőmérsékletszabályozást igényel a szükséges szemcsefinomítás eléréséhez anélkül, hogy az anyag integritása sérülne.

Hidegforgácsolás: Ez a módszer fémeket alakít ki környezeti hőmérsékleten vagy ahhoz közeli hőmérsékleten, aminek következtében növekszik a keménység és szűkülnek a tűréshatárok. Bár a hidegforgatás nagyobb erőt igényel az anyag ellenállása miatt, kitűnő felületminőséget és méretpontosságot eredményez. A hidegen kovácsolt alkatrészek gyakran kevesebb utómegmunkálást igényelnek, mint a melegen kovácsolt megfelelőik.

Az alumínium vagy más fémek meleg- vagy hidegforgatása közötti választás a bonyolultságra, pontosságra és mechanikai tulajdonságokra vonatkozó konkrét igényektől függ. A formaöntéssel vagy öntéssel készült alkatrészek és a kovácsolt darabok közti különbség megértése visszavezethető erre a kovácsolás által biztosított szabályozott alakváltoztatási folyamatra.

Kovácsolási műveletek típusai

Nem minden kovácsolás egyforma. A kiválasztott konkrét technika jelentősen befolyásolja a végső termék jellemzőit:

Nyitott űrű kovácsolás: Szabadkovácsolásnak vagy kovácsoltatásnak is nevezik, ez a folyamat sík, félkör alakú vagy V-alakú üllőket használ, amelyek soha nem zárják teljesen körbe a fém anyagot. A munkadarabot addig kalapálják vagy sajtolják ismételt ütésekkel, amíg el nem érik a kívánt alakot. Bár a nyílt üllőjű kovácsolás esetén minimális az eszközgyártási költség és alkalmas néhány centimétertől majdnem 100 láb hosszúságú alkatrészek előállítására, általában szükség van további pontossági megmunkálásra a szoros tűréshatárok betartásához.

Zárt űrű kovácsolás: Ez a módszer a fém anyagot speciálisan megformázott, teljesen körbezáró sablonok közé helyezi. A nyomóerő hatására az anyag kitölti a sablonüregeket. A zárt üllőjű kovácsolás egyike a leggyakrabban használt eljárásoknak acél- és alumíniumkovácsolás során, mivel a fém belső szemcseszerkezetével dolgozik, így erősebb, hosszabb élettartamú termékek készülhetnek. A folyamat kihasználja a többletanyagot (a kovácsolás során kinyomódó úgynevezett pernyét) is, hiszen a lehűlő többletanyag növeli a nyomást, így elősegíti, hogy a fém finom részletekbe is beáramoljon.

Kontúrkovácsolás: A zárt alakú kovácsolás egyik fajtája, amely pontosan megmunkált formaüregeket használ összetett geometriák létrehozásához. Ideális megoldás olyan kovácsolt futógyűrű alkatrészek, hajtórudak és egyéb bonyolult alkatrészek gyártására, ahol a méretpontosság kiemelten fontos.

Szemcseirányultság és szerkezeti előnyei

Itt válik igazán szét a kovácsolás más gyártási módszerektől. Amikor a fém kovácsolásnak van kitéve, a belső szemecsés szerkezet nem csupán deformálódik; hanem az anyagáramlási iránynak megfelelően rendeződik, amit a mérnökök „szemcseirányultság” néven ismernek. Ez az irányultság a kovácsolt alkatrészek kiváló teljesítményének titka.

A szerint, anyagtudományi kutatások szerint Welong műszaki forrásai , a hőmérséklet, nyomás és alakváltozási sebesség szabályozása a kovácsolás során közvetlenül befolyásolja a szemcseméret finomodását. A Hall-Petch-összefüggés kimondja, hogy ahogy a szemcseméret csökken, az anyag szilárdsága növekszik, mivel a szemcsehatárok akadályozzák a diszlokációk mozgását.

A megfelelő szemcseáramlás-igazítás eredményeként kialakuló főbb jellemzők a következők:

- Irányított szilárdság a szemcseirányultságból: A szemcsék megnyúlnak és párhuzamosan rendeződnek a fő terhelési iránnyal, ezzel rostos szerkezetet hozva létre, amely kiváló szilárdságot és merevséget biztosít a kritikus igénybevételi tengelyek mentén. Ez a kovácsolt alkatrészeket ideálissá teszi olyan alkalmazásokhoz, mint a hajtórudak vagy a forgattyús tengelyek, ahol a terhelések előrejelezhető útvonalakon haladnak.

- Belső üregek megszüntetése: A kovácsolás során ható nyomóerők bezárják a pórusokat, és megszüntetik a belső üregeket, amelyek gyakran jelen vannak öntött vagy rézötvözetből készült alkatrészekben. Ennek eredménye egy sűrűbb, homogénebb anyagszerkezet.

- Kiváló fáradásállóság: Az egymással párhuzamosan rendezett szemcsestruktúra természetes akadályokat hoz létre, amelyek gátolják a repedések terjedését. A repedéseknek több, a növekedési irányra merőlegesen tájolt határon is át kell hatolniuk, ami hatékonyan lassítja vagy megállítja a meghibásodást. Ez közvetlenül hozzájárul a javult fáradási élettartamhoz ciklikus terhelési körülmények között.

A kovácsolás folyamatából származó finom szemcsézetű anyagok javított alakíthatósággal és ütőméréssel is rendelkeznek. A nagyobb szemcsehatár-felület valójában nagyobb alakváltozást tesz lehetővé törés előtt, miközben egyidejűleg magasabb törési szívósságot biztosít a repedések terjedésének megakadályozásával.

Kovácsolás és másodlagos műveletek

Bár a zártzárú kovácsolással lenyűgöző mérettűrést lehet elérni, számos alkalmazás esetében további megmunkálás szükséges a végső tűrések betartásához. A kovácsolás és a CNC megmunkálás kapcsolata kiegészítő, nem versengő jellegű.

A nyíltzárú kovácsolatok majdnem mindig igényelnek precíziós megmunkálást a folyamat befejezéséhez, mivel a kalapáccsal történő alakítás pontatlan méreteket eredményez. A zártzárú kovácsolatok viszont gyakran kevés vagy egyáltalán nincs szükség megmunkálásra a szigorúbb tűrések és az állandó lenyomatok miatt. Ez a csökkentett megmunkálási igény költségmegtakarításhoz és gyorsabb gyártási ciklusokhoz vezet nagy sorozatgyártás esetén.

Az optimális megközelítés gyakran a kovácsolás szemcseszerkezeti előnyeit kombinálja a CNC megmunkálás pontosságával. Így megkapja az alkatrész alapkomponensének mechanikai előnyeit, miközben eléri az összeszerelés által igényelt pontos tűréseket.

A kovácsolás fémrudakat alakító hatásának ismeretében most már készen áll arra, hogy megismerje, hogyan alakítja a sajtolás teljesen más módon a fémmegmunkálási profilokat.

A sajtolási folyamat bemutatása

Míg a kovácsolás több irányból ható nyomóerővel alakítja át a fémeket, addig a fémextrudálás teljesen más módszert alkalmaz. Képzelje el, ahogy fogkrémet nyom ki egy tubusból. A krém pontosan az aperture alakjában jelenik meg, és végig ugyanazt a keresztmetszetet tartja meg hosszában. Ez az egyszerű analógia ragadja meg azt, ahogyan az ipari léptékű fémextrudálás működik.

Az extrudált alumínium eljárás és hasonló technikák más fémek esetében is alapvetővé váltak a modern gyártásban. A Technavio iparági kutatása szerint az alumínium extrudálás globális kereslete várhatóan körülbelül 4%-kal nőtt 2019 és 2023 között. Ez a növekedés tükrözi az eljárás egyedülálló képességét, hogy összetett keresztmetszetű profilokat hatékonyan és gazdaságosan állítson elő.

Fémek préselése precíziós sablonokon keresztül

Tehát mi is az extrudálás lényege? Az eljárás során egy melegített nyomódarabot – általában hengeres formájú alumíniumötvözetet vagy más fémet – speciálisan tervezett, előre meghatározott keresztmetszetű sablonon keresztül préselnek át. Egy erős hidraulikus dugattyú akár 15 000 tonna nyomással nyomja át a kovácsolható fémet a sablon nyílásán. Az eredmény egy folyamatos profil, amely pontosan követi a sablon alakját.

Az extrúziós eljárás története több mint két évszázaddal ezelőttre nyúlik vissza. Joseph Bramah fejlesztette ki az első változatot 1797-ben ólomcsövek gyártásához. Az eljárást eredetileg „spricc” módszernek nevezték, és kézi folyamat maradt egészen addig, amíg Thomas Burr 1820-ban meg nem építette az első hidraulikus sajtot. Alexander Dick 1894-es találmánya, a meleg hely extrúzió forradalmasította az ipart, lehetővé téve a gyártók számára, hogy nem vasalapú ötvözetekkel dolgozzanak. 1904-re megépítették az első alumínium extrúziós sajtót, ami széles körű elterjedést indított el az autó- és az építőiparban.

Kétféle alapvető módszer létezik acél-, alumínium- és egyéb fémek extrudálására:

Direkt extrúzió: Ez a mai nap leggyakrabban alkalmazott módszer. Az alumíniumprofil- sajtáló egy melegített tömör rudat helyez el egy falanként melegített edényben. Egy mozgó dugattyú ezután kényszeríti a fémet egy álló alakzaton keresztül. A gépészek gyakran anyagblokkokat helyeznek el a tömör rúd és a dugattyú közé, hogy megakadályozzák az összetapadást a feldolgozás során. Ezt néha előre irányú sajtálásnak is nevezik, mivel a tömör rúd és a dugattyú azonos irányban mozog.

Indirekt sajtálás: Más néven visszafelé irányuló sajtálás, amely megfordítja a mechanikát. Az alakzat álló helyzetű marad, miközben a tömör rúd és az edény egyszerre mozog. Egy speciális, az edény hosszánál hosszabb „tengely” tartja a dugattyút, miközben a tömör rudat kényszerítik át az alakzaton. Ez a módszer kevesebb súrlódást generál, így jobb hőszabályozást és konzisztensebb termékminőséget eredményez. A hőmérséklet-stabilitás továbbá kiválóbb mechanikai tulajdonságokat és személyszerkezetet biztosít a direkt módszerekhez képest.

Az alumíniumsajtálás lépésről lépésre

Mivel az alumínium ipari elterjedtsége jelentős, az teljes alumíniumextrúzió vas és egyéb ötvözetek feldolgozási sorának megértése segít bemutatni, hogyan működik ez a gyártási folyamat:

- Szerszám előkészítés: Egy kör alakú szerszámot megmunkálnak vagy meglévő szerszámból választanak ki. Az extrúzió megkezdése előtt a szerszámot előmelegítik kb. 450–500 °C-ra, hogy biztosítsák az egyenletes félfolyását és maximalizálják a szerszám élettartamát.

- Billet előkészítés: A darabot egy hosszabbított alumíniumötvözet-rönkből vágják le, majd kb. 400–500 °C-ra előmelegítik sütőben. Ez a hőmérséklet elegendően alakíthatóvá teszi a darabot a feldolgozáshoz, miközben jól alacsonyan tartja az olvadáspontja alatt.

- Betöltés és kenés: Az előmelegített darabot mechanikusan juttatják a sajtóba. A betöltés előtt kenőanyagot visznek fel, és egy elválasztó anyaggal bevonnak az extrúziós dugattyút, hogy megakadályozzák az alkatrészek összeragadását.

- Extrúzió: A hidraulikus dugattyú hatalmas nyomást fejt ki, amely az alakítható billetet a tartályba préseli. Ahogy az alumínium kitölti a tartály falait, nyomást gyakorol az extrudáló szerszámra, és áramlik a szerszám nyílásain keresztül, teljesen kialakított formában kilépve.

- Hűtés: Egy húzóberendezés rögzíti a kilépő extrudátumot védelem céljából. Ahogy a profil végighalad a futóasztalon, ventilátorok vagy vízfürdők egyenletesen lehűtik azt, ezt a folyamatot edzésnek nevezik.

- Vágás és hűtés: Amikor az extrudálás eléri a teljes asztalhosszt, egy forró vágófűrész elvágja. Ezután az extrudátumokat átvisszák egy hűtőasztalra, ahol szobahőmérsékletre hűlnek.

- Nyújtás: A profilok gyakran torzulást fejlesztenek ki a feldolgozás során. Egy nyújtóberendezés mechanikusan megfogja a profil mindkét végét, és addig húzza, amíg teljesen egyenes nem lesz, így a méretek a megadott tűréshatárokon belülre kerülnek.

- Vágás és öregítés: A kiegyenesített extrudátumok vágóasztalhoz kerülnek, ahol meghatározott hosszúságú darabokra vágják őket, általában 8–21 lábra. Végül egy kemencébe kerülnek éretésre a megfelelő edzettségi állapot eléréséhez.

Miért kiváló az extrudálás a bonyolult keresztmetszeti profiloknál

Az extrudálási és húzó eljárások különleges előnyökkel rendelkeznek, amelyek ideálissá teszik őket meghatározott alkalmazásokhoz. Ezeknek az előnyöknek a megértése segít eldönteni, mikor válik az extrudálás a más gyártási módszereknél hatékonyabbnak:

- Üreges szelvények készítésének képessége: Ellentétben a kovácsolással, amely nehézségekbe ütközik a belső üregek kialakításánál, az extrudálás könnyedén előállít üreges profilokat, csöveket és többüreges alakzatokat. Ez a lehetőség ideálissá teszi olyan alkalmazásoknál, ahol belső csatornákra, hűtőbordákra vagy szerkezeti csövekre van szükség.

- Kiváló felületi minőség: Az extrudált profilok konzisztens, magas minőségű felületi minőséggel kerülnek ki, amely gyakran minimális másodlagos feldolgozást igényel. A pontos formákba történő szabályozott áramlás sima felületeket eredményez, amelyek készek az anódoxidálásra vagy más felületkezelésekre.

- Anyaghatékonyság minimális hulladékkal: Az extrudálás folyamatos jellege maximalizálja az anyagkihasználást. Ellentétben a rúdról történő megmunkálással, amelynél anyagot távolítanak el, az extrudálás az egész billetet hasznosítható termékké alakítja át, nagyon kevés selejttel.

- Kialakítási rugalmasság: A AS Aluminum műszaki erőforrásai , az extrudálás lehetővé teszi összetett profilok létrehozását pontos méretekkel, amelyek segítségével a tervezők olyan összetett geometriákat és egyedi alakzatokat valósíthatnak meg, amelyek hagyományos gyártási módszerekkel nehezen érhetők el.

- Költséghatékonyság: Az extrudálás magas termelési sebességet és minimális anyagveszteséget biztosít, így költséghatékony megoldást nyújt nagy- és kis léptékű gyártási sorozatok esetén is.

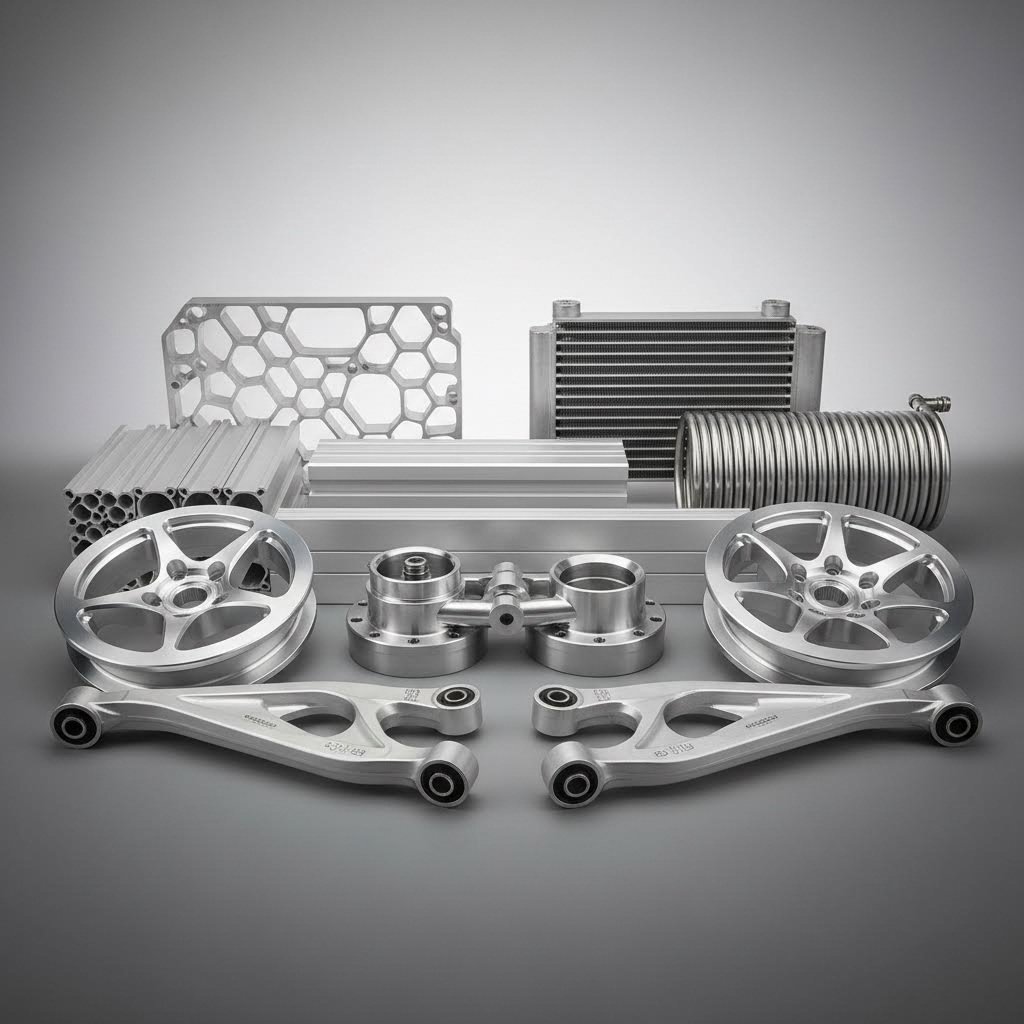

Az extrudált alakzatok négy kategóriába sorolhatók: tömör alakzatok zárt nyílások nélkül, például gerendák vagy rúd; üreges alakzatok egy vagy több üreggel, például téglalapcsövek; félig üreges alakzatok részben zárt üregekkel, például keskeny résekkel rendelkező C-profilok; valamint egyedi alakzatok, amelyek több extrudált elemet vagy egymásba kapcsolódó profilokat tartalmazhatnak, konkrét igények szerint tervezve.

Szemcseszerkezet az extrudált alkatrészekben

Itt válik legláthatóbbá az alapvető különbség a kovácsolás és az extrudálás között. Míg a kovácsolás során az anyag összenyomása közben több irányba rendeződik a személyszerkezet, addig az extrudálás során a személyek az extrudálási iránnyal párhuzamosan alakulnak ki.

A kutatások szerint, amelyeket a Nature Portfolio közzétett, az alumíniumötvözetek extrudálása rendkívül érzékeny a feldolgozási paraméterekre, mint például a hőmérséklet, a deformációs sebesség és az alakítószerszám konfigurációja. Ezek a tényezők közvetlenül befolyásolják a személyszerkezet kialakulását, a dinamikus újrakristályosodást, valamint a hegesztési varratok kialakulását a kész termékben.

Ez a párhuzamos személyelrendeződés azt jelenti, hogy az extrudált alkatrészek más mechanikai tulajdonságokkal rendelkeznek, mint a kovácsolt komponensek:

- Irányfüggő szilárdsági jellemzők: Az extrudált profilok a legnagyobb szilárdsággal rendelkeznek az extrudálási irányban. Ez ideálissá teszi őket olyan alkalmazásokhoz, ahol a terhelés elsősorban a profil hosszirányában hat, például szerkezeti elemek vagy sínrendszer esetén.

- A perifériás durva szemcsék figyelembevétele: A kutatások azt mutatják, hogy az extrudált profilok perifériás durva szemcsézetségű (PCG) réteget alakíthatnak ki a felület közelében, amely durvább szemcsékkel rendelkezik, és befolyásolhatja a mechanikai tulajdonságokat. A bélyegsík geometriájának és az üzemeltetési körülményeknek a szabályozása segít ennek a hatásnak a minimalizálásában.

- Állandó keresztmetszeti tulajdonságok: Mivel az egész keresztmetszet ugyanazon a sablonon és azonos körülmények között halad át, a mechanikai tulajdonságok az egész profil hosszában egységesek maradnak.

Az alumínium anyag természetes jellemzői tökéletesen kiegészítik az extrúziós eljárást. Kiváló szilárdság-súly arányának és a természetes oxidréteg képződéséből adódó kitűnő korrózióállóságának köszönhetően az extrudált alumíniumot az autóiparban, az űr- és repülőgépiparban, az elektronikában és az építőiparban egyaránt alkalmazzák.

Most, hogy ön már ismeri a kovácsolást és az extrúziót külön-külön, készen áll arra, hogy ezeket közvetlenül össze lehessen hasonlítani azokban a mechanikai tulajdonságokban és teljesítményparaméterekben, amelyek az ön alkalmazásai szempontjából a legfontosabbak.

Mechanikai tulajdonságok és teljesítmény összehasonlítása

Megtanulta, hogyan sűríti az űrtömbököt a kovácsolás finomra szabott, szemcetenyező komponensekké. Látta, hogyan préseli át a melegített fémeket pontos formákba az extrudálás folyamata, hogy folyamatos profilokat hozzon létre. De amikor kritikus alkalmazásra kell alkatrészeket megadnia, többre van szüksége, mint folyamatleírásokra. Kemény adatokra van szüksége, amelyek oldalról-oldalra hasonlítják össze ezeket a módszereket.

Itt marad el a legtöbb forrás. Magyarázzák az egyes folyamatokat külön-külön, de soha nem adják meg az Ön döntéshozatalához szükséges közvetlen összehasonlítást. Ezt pótoljuk most átfogó táblázatokkal, amelyek a projektjei szempontjából ténylegesen fontos kulcsfontosságú teljesítményparamétereket fedik le.

Oldalról-oldalra történő folyamatösszehasonlítás

Amikor öntött alumíniumot hasonlítunk össze kovácsolt alumíniummal, vagy összehasonlítjuk az öntött és kovácsolt alumínium alkatrészeket, valójában azt kérdezzük: melyik folyamat biztosítja azokat a mechanikai tulajdonságokat, amelyeket az alkalmazásom megkövetel? Ugyanez a kérdés merül fel a kovácsolás és az extrudálás közötti választásnál is. Íme, hogyan állnak ezek a módszerek a kritikus teljesítménymutatók szerint:

| Teljesítményparaméter | Kőművészet | Extrudálás |

|---|---|---|

| Húzóerő | Kiváló; a szemcseirányultság 10-30%-kal növeli a szilárdságot a feszültségi tengelyek mentén öntött megfelelőkhöz képest | Jó; a szilárdság az extrudálás irányában koncentrálódik; a keresztmetszeti tulajdonságok állandóak maradnak |

| Törékenyseg elleni ellenállás | Kiváló; az egymásba illeszkedő szemcsehatárok akadályozzák a repedések terjedését, így optimális körülmények között 3-7-szeresre nő a fáradási élettartam | Közepes jó; a párhuzamos szemcseáramlás irányfüggő fáradási ellenállást biztosít a profil hossza mentén |

| Az ütközés ellenállása | Kiváló; a pórusmentesítés és a szemcsefinomítás sűrű, ütődőképes anyagszerkezetet eredményez | Jó; az állandó keresztmetszet előrejelezhető ütésállóságot biztosít a profil hossza mentén |

| Méret toleranciák | Melegkovácsolás: tipikusan ±0,5 mm-tól ±1,5 mm-ig; hidegkovácsolás: ±0,1 mm-tól ±0,3 mm-ig elérhető | tipikusan ±0,1 mm-tól ±0,5 mm-ig; az indirekt extrudálás szűkebb tűréshatárokat ér el a csökkentett súrlódás miatt |

| Felületi minőség | Melegkovácsolás: Ra 6,3–12,5 μm (megmunkálás szükséges); hidegkovácsolás: Ra 0,8–3,2 μm | Ra 0,8–3,2 μm; kiváló, extrudált állapotban is gyakran alkalmas anodizálásra másodlagos feldolgozás nélkül |

| Geometriai összetettség | Magas; összetett 3D alakzatok, zárt üregek és aszimmetrikus formák kialakítására képes zártdiovas eljárással | Közepes; kitűnő összetett 2D keresztmetszetek, beleértve a csöves profilok előállításában; hosszirányban csak egyenletes keresztmetszetek esetén alkalmazható |

| Anyaghasznosítási arány | 75–85% tipikus; a peremező anyagot gyakran újra lehet hasznosítani | 90–95%+ tipikus; folyamatos feldolgozás miatt minimális a hulladék |

| Tipikus gyártási mennyiségek | Közepes és magas; az eszközök költsége nagyobb tételnagyság (1000+ darab zártdiovas eljárásnál) esetén kedvezőbb | Alacsonytól magasig terjedő; az extrudálószerszámok költsége alacsonyabb, mint a kovácsoló szerszámoké; rövidebb sorozatoknál is gazdaságos |

Ha öntött és kovácsolt acélt hasonlítanak össze, vagy öntés és kovácsolás közötti lehetőségeket értékelik alkalmazásukhoz, fontos megérteni a kovácsolás és az öntés közötti különbséget. A kutatások szerint a Waterloo-i Egyetem fáradási vizsgálataiból , az optimális hőmérsékleten feldolgozott, kovácsolt AZ80 magnézium alkatrészek kb. 3-szoros fáradási élettartamot mutattak 180 MPa-n és 7-szereset 140 MPa-n, összehasonlítva a magasabb hőmérsékletű alternatívákhoz képest. Ez kiemeli, hogy milyen drámaian befolyásolják a folyamatparaméterek a végső teljesítményt.

Főbb teljesítményjellemzők értékelése

A fenti táblázat áttekintést nyújt, de nézzük meg részletesebben, mit jelentenek ezek a számok a gyakorlati alkalmazásokban.

Szilárdsági jellemzők megértése: A kovácsolás szuperiórussága a húzó- és fáradási szilárdság terén közvetlenül a szemcseirányultság rendeződéséből ered. Amikor összehasonlítjuk az öntést és a kovácsolást, tartsuk észben, hogy a kovácsolt alkatrészek belső kristályszerkezete újraszerveződik, hogy kövesse az alkatrész geometriáját. Ez természetes megerősítést hoz létre a fő igénybevételi irányok mentén.

A szélesítés viszont a profil hosszában állandó szilárdságot biztosít. Ez ideálissá teszi a kihúzott alkatrészeket olyan szerkezeti elemek, sínvezetések és keretek esetén, ahol a terhelés a kihúzás irányába esik. Azonban a kihúzási tengelyre merőleges terhelések másképp érik el a szemcsehatárokat, ami az adott irányokban alacsonyabb szilárdsághoz vezethet.

Tűréshatár specifikációk magyarázata: A hideg szélesítés tűréseket érhet el akár ±0,02 mm-es pontossággal is közvetlenül a szerszámból a pontossági gyártási kutatások szerint. Ez jelentősen csökkenti a másodlagos megmunkálást, amire a melegkovácsolás általában szükségeltetik. A kovácsolás és öntés közötti különbség a méretpontosság tekintetében jelentős. A kovácsolás szigorúbb tűréseket biztosít az öntésnél, de kritikus méretek esetén még így is szükség lehet befejező megmunkálásra.

Felületminőség figyelembevétele: Ha az alkalmazás esztétikus felületeket vagy tömítőfelületeket igényel, az extrudálás gyakran közvetlenül használható felületet eredményez. A melegkovácsolás magas hőmérsékleten oxidációt és hártyaképződést okoz, amely további tisztítást vagy megmunkálást igényel. A hidegkovácsolás ezt a hiányosságot orvosolja, mivel fényes felületet állít elő termikus oxidáció nélkül.

Anyagkompatibilitási elemzés

Nem minden fém alkalmas egyformán mindkét eljárásra. Az anyag kiválasztása jelentősen befolyásolja, hogy melyik alakítási módszer szolgáltat optimális eredményt. Íme, hogyan viselkednek a gyakori mérnöki fémek az egyes technikák esetén:

| Fém/ötvözet | Kovácsolhatóság | Extrudálhatóság | Ajánlott eljárás indoklása |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alumínium ötvözetek (6061, 7075) | Kiváló minőségű nagy szilárdságú alkalmazásokhoz; a 7075-es kovácsolt alumínium kiváló súly- és szilárdságarányt nyújt | Kiváló; az alumínium jól alakítható, ezért a leggyakrabban extrudált fém; a 6061-es profilok dominálnak az építőiparban és az autóiparban | Extrudálás profilokhoz és szerkezeti alakzatokhoz; kovácsolás olyan nagy terhelésű alkatrészekhez, amelyek több irányból származó szilárdságot igényelnek |

| Szén- és ötvözött acélok | Kiváló; a melegkovácsolást széles körben használják járműipari, nehézgép-ipari és ipari alkatrészeknél | Mérsékelt; a acél extrudálása kevésbé elterjedt a magasabb alakítási nyomások miatt; hideg extrudálást használnak csavarokhoz és kisebb alkatrészekhez | A kovácsolás az acél legtöbb alkalmazásánál előnyös; az extrudálás speciális profilokra és hidegen alakított alkatrészekre korlátozódik |

| Rosttalan acélok | Jó – kiváló; megfelelő hőmérséklet-szabályozás szükséges a karbidkiválás megelőzéséhez | Mérsékelt; a keményedési hajlam növeli az extrudálási erőket; általában meleg feldolgozást igényel | Kovácsolás összetett alakú alkatrészekhez; extrudálás csövekhez és profilokhoz, ahol fontos a keresztmetszeti korrózióállóság |

| Sárgaréz és rézötvözetek | Jó; sárgaréz kovácsolatokat használnak szelepekben, csatlakozókban és szerelvényekben | Kiváló; extrudált sárgaréz és sárgaréz extrudálási profilok széleskörűen használatosak építészeti és vízvezeték-alkalmazásokban | Extrudálás egységes profilokhoz és díszítő alkalmazásokhoz; kovácsolás összetett szeleptestekhez és nagy szilárdságú szerelvényekhez |

| Titánötvözetek | Jó; pontos hőmérséklet-szabályozást és speciális szerszámokat igényel; űrrepülési minőségű alkatrészek előállítására alkalmas | Korlátozott; a nagy szilárdság és alacsony hővezető képesség miatt nehézkes az extrudálás; speciális felszerelés szükséges | A titan esetében erősen ajánlott a kovácsolás; kiváló szemcseszerkezetet eredményez, amely ideális az űrrepülési és orvosi alkalmazásokhoz |

| Magnéziumötvözetek (AZ80) | Kiváló, ha megfelelően dolgozzák fel; kutatások szerint optimális tulajdonságok érhetők el 300 °C-os kovácsolási hőmérsékleten | Jó; a magnézium jól extrudálható, de gondos hőmérséklet-kezelés szükséges a repedések elkerüléséhez | Kovácsolás járműipari szerkezeti alkatrészekhez; extrudálás olyan profilokhoz, ahol a tömegcsökkentés indokolja a speciális feldolgozást |

Hogyan határozzák meg az anyagjellemzők a gyártási eljárást

Annak megértése, hogy egyes anyagok miért részesítik előnyben az egyik eljárást, segít jobb beszerzési döntések meghozatalában:

- Az alumínium sokoldalúsága: Az alumíniumötvözetek mindkét folyamatban kiválóan teljesítenek kitűnő alakíthatóságuk és széles feldolgozási hőmérsékleti tartományuk miatt. Az öntött alumínium és az extrudált alumínium közötti választás inkább a geometriától és a terhelési igényektől függ, semmint anyagi korlátozásoktól.

- Acél kovácsolásának előnye: Az acél nagy szilárdsága és hidegalakításkor történő keményedése miatt a kovácsolás a domináns alakítási módszer. A kovácsolás hatékonyan alkalmaz erőt az acélsötétre, míg az extrudáláshoz lényegesen magasabb nyomás szükséges, ami korlátozza a gyakorlati alkalmazhatóságát.

- Titán feldolgozási kihívásai: A titán nagy szilárdság-súlyaránya és biokompatibilitása miatt nélkülözhetetlen az űr- és orvostechnikai alkalmazásokban. Ugyanakkor alacsony hővezető-képessége és magas hőmérsékleten történő nagy reakcióképessége miatt a kovácsolás az elsőbbséget élvező módszer a megfelelő szemcsestruktúra elérésében.

- Rézötvözet (bronz) alkalmazásai: A rézötvözetek mind kovácsolással, mind sajtolással előállított változatai fontos ipari szerepet töltenek be. A sajtolt rézötvözet az építészeti és vízszerelési alkalmazásokban dominál, ahol az egységes profilok lényegesek. A kovácsolt rézalkatrészek pedig olyan szelepekben és csatlakozókban jelennek meg, ahol a háromdimenziós bonyolultság és a nyomásállóság kritikus.

Miután ezt az összehasonlító alapot kialakítottuk, most már készen állhat arra, hogy megvizsgálja, hogyan tükröződnek ezek a teljesítménybeli különbségek a költségtényezőkben és a termelési mennyiségek gazdaságosságában.

Költségtényezők és a termelési mennyiségek gazdaságossága

Látta a mechanikai tulajdonságok közötti különbségeket. Megértette, hogyan hat a személyszerkezet a teljesítményre. De itt jön a döntő kérdés, amely gyakran meghatározza a végső döntést: valójában mennyibe fog kerülni? Amikor öntött és kovácsolt alkatrészeket hasonlít össze, vagy sajtolt alternatívákat értékel, a gazdaságosság messze túlmutat az egyedi alkatrész árán, amit egy árajánlaton lát.

A valódi költségkép megértéséhez meg kell vizsgálni a szerszáminstallációk, egységre jutó költségek és azon termelési mennyiségi küszöbök kérdését, ahol mindegyik eljárás versenyképes lesz. Nézzük át részletesen a pénzügyi tényezőket, amelyeknek alakítaniuk kellene gyártási döntéseit.

Szerszáminstalláció és egységre jutó költségek

Az egyes eljárásokhoz szükséges kezdeti beruházás drámaian eltér, és ez az eltérés alapvetően meghatározza, hogy mikor válik gazdaságossá az egyes módszerek alkalmazása.

Kovácsolási szerszámköltségek: Az egyedi kovácsolt alkatrészekhez precíziós sablonokra van szükség, amelyeket edzett szerszámacélból kell megmunkálni. Ezek a sablonoknak ki kell bírniuk a nagy nyomóerőket emelt hőmérsékleten, ami drága anyagokat és gondos hőkezelést igényel. Egyetlen záródieles kovácsolóforma költsége darab bonyolultságától, méretétől és előírt tűréseitől függően 10 000 és 100 000 dollár felett is lehet. A nagy ipari alkatrészeket gyártó öntőkovácsoló üzemeknél a szerszáminstalláció költségei még tovább emelkedhetnek.

Extrúziós sablonok gazdaságossága: Az extrúziós szerszámok, bár továbbra is precíziós megmunkálásúak, a legtöbb alkalmazásban lényegesen olcsóbbak, mint az űrt sajtoló szerszámok. A szabványos alumínium extrúziós szerszámok általában 500 és 5000 USD között mozognak, míg az összetett többüreges üreges szerszámok elérhetik a 10 000–20 000 USD-t. Ez az alacsonyabb szerszámköltség gazdaságilag életképessé teszi az extrúziót rövidebb gyártási sorozatoknál és prototípus-fejlesztésnél.

Itt fordul meg az egységköltségek kérdése. Annak ellenére, hogy a szerszámköltségek magasabbak, nagyobb darabszámnál a sajtolás gyakran alacsonyabb darabköltséget eredményez. A bA Forging iparági elemzése szerint a sajtolás és öntés összehasonlítása azt mutatja, hogy a sajtolás ciklusideje az egyes alkatrészeknél rendkívül gyors lehet, miután a szerszámok készen állnak. Egyetlen sajtoló prés ciklus néhány másodperc alatt előállíthat egy közel végleges geometriájú alkatrészt, míg ugyanezt a geometriát megmunkálással órákig tartana elérni.

A teljes beruházás mértékét meghatározó költségtényezők a következők:

- Kezdeti szerszáminverzió: Az űrtartó formák ára 5–20-szor magasabb az extrudáló formákénál összehasonlító alkalmazások esetén. Azonban megfelelő karbantartás mellett az űrtartó formák gyakran hosszabb ideig tartanak, így a költségük több darabra oszlik el.

- Anyagköltségek és hulladék ráta: Extrudálással 90–95%+ anyagkihasználás érhető el az űrtartásos kovácsolás 75–85%-ával szemben. Drága ötvözetek esetén ez a különbség jelentősen befolyásolja az összes anyagköltséget. A kovácsolásból származó pernye újrafeldolgozható, de az újrafeldolgozás további költségekkel jár.

- Ciklusidők: Zárt űrtartásos kovácsolással összetett alakzatok állíthatók elő egy vagy néhány sajtoló ciklusban. Az extrudálás folyamatosan működik, így különösen hatékony hosszú sorozatgyártásnál azonos profilok esetén.

- Másodlagos műveletek igénye: A meleg kovácsolás általában több utómegmunkálást igényel, mint az extrudálás. A hideg kovácsolás és a precíziós extrudálás is minimalizálja a másodlagos műveleteket, de mindegyik más-más geometriai lehetőségekhez alkalmas.

A megtérülési pont meghatározása

Tehát mikor térül meg a kovácsolás magasabb szerszámköltsége? A válasz az Ön konkrét alkatrész-igényeitől függ, de általános küszöbértékek segítenek megvilágítani a döntést.

A legtöbb záródiovas kovácsolási alkalmazásnál az évi 1000–5000 darabos gyártási mennyiség már akkor gazdaságossá válik, ha a teljes tulajdonlási költséget összehasonlítjuk a rúdanyagból történő megmunkálással. 10 000 darab felett a kovácsolás jellemzően egyértelmű költségelőnyt nyújt összetett háromdimenziós geometriák esetén.

Az extrudálásnál a hozamhatár lényegesen hamarabb elérhető. Az alacsonyabb sablonköltségek miatt már 500–1000 futóláb (kb. 150–300 méter) profilhossz is indokolttá teheti az egyedi szerszámokat. Szabványos formák meglévő sablonokkal történő gyártása esetén gyakorlatilag nincs minimális rendelési korlát az anyagmozgatási logisztikán túl.

Elkészítési idő figyelembevétele: A szerszámgyártási idő jelentősen befolyásolja a projekt ütemtervét. A kovácsolószerszámok tervezésére, megmunkálására és hőkezelésére 4–12 hét szükséges a bonyolultságtól függően. Az extrudáló szerszámok általában 2–4 hét alatt érkeznek meg. Ha fontos a gyors piaci bevezetés, az extrudálás gyakran biztosít gyorsabb kezdeti termelési lehetőséget.

Folyamatkiválasztási keretrendszer mennyiség szerint:

- Prototípus – 500 darabig: Gépi megmunkálás vagy extrudálás általában a leggazdaságosabb, kivéve, ha a geometria miatt szükség van a kovácsolás szemcsestruktúrájának előnyeire

- 500–5 000 darab: Értékelje a teljes költséget, beleértve az eszközköltségek elszámolását; az extrudálás előnyben részesül a profiloknál, a kovácsolás pedig összetett 3D formák nagy szilárdsági igénye esetén

- 5 000–50 000 darab: A kovácsolás egyre versenyképesebbé válik; az eszközköltségek eloszlanak a nagyobb mennyiségen; egységköltség-megtakarítások halmozódnak

- 50 000+ darab: Kovácsolás gyakran biztosítja a legalacsonyabb teljes költséget a megfelelő geometriák esetén; kovácsolt-öntött hibrid megközelítések bizonyos alkalmazásokat optimalizálhatnak

Ne feledje, hogy ezek a küszöbértékek a alkatrész bonyolultságától, az anyagköltségektől és a másodlagos műveletek igényeitől függően változnak. Egy egyszerű kovácsolt alátét más termelési mennyiségnél éri el a hozamvisszatérési pontot, mint egy összetett futóműkar. A kulcs a teljes tulajdonlási költség kiszámítása, beleértve az eszközölést, anyagot, feldolgozást és felületkezelést az adott alkalmazásra vonatkozóan.

Miután feltérképezték a költségtényezőket, készen áll arra, hogy megismerje, hogyan kombinálódnak ezek a gazdasági tényezők a technikai követelményekkel az egyes iparági alkalmazásokban.

Ipari alkalmazások és valós világbeli használati esetek

Most, hogy megértette a költségdinamikát és a mechanikai tulajdonságok közötti különbségeket, nézzük meg, hogyan hatnak ezek a tényezők a tényleges gyártási döntésekre. Amikor a mérnökök alumínium kovácsolást írnak elő egy leszállófogas alkatrészhez, vagy extrudált rézötvözetet választanak egy építészeti alkalmazáshoz, akkor a technikai követelményeket mérik fel a gyakorlati korlátokkal szemben.

A kovácsolás és az extrudálás közötti különbségek akkor válnak legvilágosabban láthatóvá, amikor iparág-specifikus alkalmazásokat vizsgálunk. Mindegyik szektor évtizedekre visszamenő teljesítményadatok, hibaelemzések és folyamatos fejlesztések alapján alakította ki preferenciáit. Ezeknek a mintázatoknak az ismerete segít megalapozott döntéseket hozni saját projektekhez.

Gépjármű- és repülőgépipari alkatrész-kiválasztás

Gondoljon arra, mi történik, ha egy futómű-kar elszakad autópályán vagy ha egy leszállófutó szerelvénye megreped landoláskor. Ezek nem elméleti esetek – pontosan ezek a hibamódok határozzák meg az anyagok és gyártási eljárások kiválasztását ebben a követelőző iparágban.

Autóipari alkalmazások: Az autóipar az egyik legnagyobb fogyasztója a kovácsolt és az extrudált alkatrészeknek. A futóműkarok, kormányzott féltengelyek és kerékagyak túlnyomórészt kovácsolással készülnek, mivel ezek az alkatrészek kanyarodás, fékezés és ütközések során összetett, többirányú terhelésnek vannak kitéve. A kovácsolás során kialakuló szemcseirányultság olyan természetes erősítési utakat hoz létre, amelyek követik a feszültségkoncentrációk helyét.

A meghajtótengelyek érdekes esettanulmányt jelentenek. Míg maga a tengely súlyhatékonysági okokból extrudált cső lehet, a végcsatlakozók és kapcsok általában kovácsoltak. Ez a hibrid megközelítés ötvözi az extrudálás anyaghatékonyságát a konstans keresztmetszetű szakaszoknál a kovácsolás kiváló fáradási ellenállásával a nagy igénybevételű csatlakozási pontokon.

Repülőgépipari követelmények: A repülőipari alkalmazások mindkét eljárást a határaikig terhelik. Az alumíniumkovácsolás elsősorban nagy szilárdságú szerkezeti csatlakozóelemek, leszállófutó alkatrészek és bordák rögzítései esetén dominál, ahol a meghibásodás katasztrofális lenne. Az alumínium extrudálási gyártási folyamat viszont kitűnően alkalmas hosszgerendákra, futópántokra és szerkezeti csatornákra, amelyek a repülőgéptestek és szárnyak mentén húzódnak.

A repülőipar érdekességét az extrém dokumentációs követelmények adják. A kovácsolt és extrudált repülőipari alkatrészek esetében teljes anyagnyomozhatóságra, eljárástanúsításra és kiterjedt rombolásmentes vizsgálatokra van szükség. Az extrudáló üzemeknek, amelyek repülőipari megrendeléseket gyártanak, AS9100 minősítéssel kell rendelkezniük, és folyamatosan bizonyítaniuk kell az egyes gyártási tételsorozatok során az egységes anyagtani tulajdonságokat.

Ipari berendezések és szerkezeti alkalmazások

A közlekedésen túl az ipari gépek és az építőipar más követelményeket támaszt, amelyek gyakran az extrudálás profilgyártási képességeit részesítik előnyben.

Ipari gépek: A nehézgépek tömörített rézötvözeteket használnak szeleptestekhez, hidraulikus csatlakozókhoz és nyomás alatt álló alkatrészekhez, ahol a tömítettség kritikus fontosságú. A kovácsolás kiküszöböli a pórusokat, amelyek nyomás alatt szivárgási utakat hozhatnának létre. Eközben a rézötvözet extrudálása költséghatékony megoldást nyújt vezetőrudakhoz, csapágyházakhoz és kopásálló sávokhoz, ahol az egységes keresztmetszet leegyszerűsíti a gyártást.

Építés és építészeti tervezés: Extrudált rézötvözet és alumínium profilok dominálnak az építészeti alkalmazásokban. Ablakkeretek, függönyfal-rendszerek és díszítő elemek az extrudálás komplex, hosszú, állandó profilok előállítására való képességére támaszkodnak. A kiváló, extrudáláskor keletkező felületi minőség kitűnően alkalmas anódos oxidálásra, így biztosítva az esztétikai igényeket, amelyek ezekben a területeken elvártak.

| IPAR | Tipikus kovácsolási alkalmazások | Tipikus extrudálási alkalmazások | Kiválasztás indoklása |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autóipar | Felfüggesztés karok, kormányzár tengelyek, kerékagyak, forgattyúk, hajtórúd | Ütközéselhárító szerkezetek, ütközőrudak, ajtónyitás elleni merevítések, hőcserélő csövek | Kovácsolás többirányú terheléshez és fáradásra érzékeny alkatrészekhez; Sajtolás energiát elnyelő szerkezetekhez és állandó keresztmetszetekhez |

| Légiközlekedés | Futómű-csatlakozók, bordák rögzítései, motorfogantyúk, szárnygyökér csatlakozók | Törzs gerendái, szárny merevítők, üléssínek, padlótartó gerendák | Kovácsolás koncentrált feszültségpontokhoz és biztonságtechnikai szempontból kritikus kapcsolatokhoz; Sajtolás hosszanti szerkezeti elemekhez, melyek állandó tulajdonságokat igényelnek |

| Olaj és gáz | Szeleptestek, fúrófej-alkatrészek, fúrószál-csatlakozások, flange-k | Fúrócsövek, köpenycsövek, csővezetékek, hőcserélő profilok | Kovácsolás nyomástartó rendszerekhez és csatlakozások integritásához; Sajtolás csőtermékekhez és áramlási utakhoz |

| Felépítés | Horgonycsavarok, szerkezeti kapcsolatok, darualkatrészek, emelési szerelvények | Ablakkeretek, előtető tartószerkezetei, szerkezeti csatornák, korlátok | Kovácsolás pontszerűen terhelt kapcsolatokhoz és megemelésre minősített szerelvényekhez; Sajtolás építészeti profilokhoz és szerkezeti elemekhez |

| Nagy terhes berendezés | Lánctáblák, gödrözőfogak, hidraulikus hengerek végdarabjai, fogaskerék-alaptestek | Hengercsövek, vezetősintrak, szerkezeti karok, kopásálló sávok | Kovácsolás kopásállóság és ütőterhelés elviselése céljából; extrudálás egységes furatfelületek és szerkezeti alakzatok érdekében |

Hibrid gyártási megközelítések

Itt van valami, amit a legtöbb forrás teljesen figyelmen kívül hagy: a legkifinomultabb gyártók gyakran kombinálják a kovácsolást és öntést, vagy az egyik eljárást használják előformaként a másikhoz. Ez a hibrid megközelítés több eljárás előnyeit is magában foglalja.

Extrudált előformák kovácsoláshoz: Egyes gyártók extrudált tömbből vagy profilból indulnak ki, majd azt kovácsolják a végső alakra. Az extrudálás egységes kiindulóanyagot hoz létre szabályozott szemcsestruktúrával, míg a kovácsolás tovább finomítja a szemcséket, és kialakítja a végső geometriát. Ez a módszer különösen jól alkalmazható olyan alkatrészeknél, mint a repülőgépek csatlakozóelemei, ahol a kiinduló anyag minősége és a végső szemcseirányultság is fontos.

Kovácsolt betétek extrudált szerelvényekben: Az autóipari ütközési szerkezetek gyakran kombinálják az extrudált alumíniumprofilokat kovácsolt csatlakozó elemekkel. Az extrúzió biztosítja az energiát elnyelő tömörödési zónát, míg a kovácsolt csomópontok biztosítják, hogy a szerkezet az ütközés során is csatlakozva maradjon a járműhöz.

Szekvenciális feldolgozás előnyei: A két folyamat ismeretében hibrid megoldásokat határozhat meg, amelyeket egyik folyamat önmagában sem tudna elérni. Egy kovácsolt központ és egy extrudált tengely hegesztve egymáshoz optimális tulajdonságokat nyújt minden szakaszon, miközben minimalizálja az összes költséget és súlyt.

Környezeti és fenntarthatósági megfontolások

A fenntarthatóság egyre inkább befolyásolja a gyártási döntéseket, és a kovácsolásnak valamint az extrúziónak eltérő környezeti jellemzői vannak, amelyeket érdemes figyelembe venni.

Energiafogyasztás: Mindkét folyamat jelentős energiabefektetést igényel a fűtéshez és a mechanikai munkához. A melegkovácsolás energiafelhasználása a billet fűtésére és az sajtoló üzemeltetésére irányul, míg az extrudálás a billet előmelegítését és hidraulikus teljesítményt igényel. Mindkét eljárás lényegesen energiatakarékosabb, mint az egyenértékű alkatrészek forgácsolása rúdrácsból, mivel anyagmozgatásról van szó, nem anyageltávolításról.

Anyaghatékonyság: Az extrudálás 90–95%-os anyagkihasználási rátája fenntarthatósági előnyt jelent a kovácsolás 75–85%-os arányához képest. Olyan szervezetek számára, amelyek komponensenként mérik a szénlábatnyomot, ez a különbség fontos. Ugyanakkor a kovácsolásnál keletkező peremanyag nagyon jól újrahasznosítható, gyakran közvetlenül visszakerül az olvasztóüzembe újrafeldolgozásra.

Termék élettartama: Életciklus-szemléletből nézve az űrt alkatrészek gyakran túlélnek más alternatívákat. Egy űrt felfüggesztési alkatrész, amely a jármű teljes élettartama alatt kiszolgálja magát, jobb fenntarthatósági eredményt jelent, mint egy könnyebb, de cserére szoruló alternatíva. Ezt a tartóssági előnyt figyelembe kell venni a teljes környezeti hatás értékelése során.

Újrahasznosíthatóság: Az űrt és sajtolt alumínium-, valamint acélalkatrészek az élettartam végén teljes mértékben újrahasznosíthatók. A mindkét folyamatból származó magas anyagtisztaság lehetővé teszi a zárt ciklusú újrahasznosítást jelentős minőségromlás nélkül.

Miután megismerte ezeket az iparági alkalmazásokat és fenntarthatósági szempontokat, készen áll arra, hogy saját alkatrész-kiválasztási kihívásaira egy szisztematikus döntéshozatali keretet alkalmazzon.

Folyamatkiválasztási keret saját projektjéhez

Áttekintette a technikai különbségeket, a költségtényezőket és az ipari alkalmazásokat. Most elérkezett a gyakorlati kérdés: hogyan döntjön a saját projektje számára a kovácsolás és az extrudálás között? A rossz választás túlméretezett alkatrészekhez, felesleges költségekhez vagy ami még rosszabb, meghibásodásokhoz vezethet a terepen, amelyek károsítják a hírnevét és a nyereségét.

Ez a döntéshozatali keretrendszer lépésről lépésre végigvezeti Önt az értékelési folyamaton. Akár először határoz meg alkatrészeket, akár meglévő tervezést tekint át, ezek a kritériumok segítenek az eljárások képességeit a tényleges igényekhez igazítani.

Az eljárások képességeinek összeegyeztetése az alkatrészek követelményeivel

Tekintsünk az eljárás kiválasztására úgy, mint egy rendszerezett kizárási gyakorlatra. Minden kritérium szűkíti a lehetőségeket, amíg az optimális választás egyértelművé nem válik. Íme a logikai folyamat, amelyet a tapasztalt mérnökök követnek:

- Határozza meg a szilárdsági és fáradási követelményeket: Kezdje a végfelhasználási terhelési feltételekkel. Milyen erők hatnak az alkatrészre? A terhelések statikusak, ciklikusak vagy ütésalapúak? Az alumíniumkovácsolás kiváló fáradási ellenállást biztosít, ha az alkatrészek többirányú ciklikus terhelésnek vannak kitéve – gondoljon például futóműkarokra vagy hajtótengelyekre. Ha a fő terhelések egyetlen tengely mentén hatnak és viszonylag statikusak, akkor a fémextrúziós eljárás elegendő szilárdságot nyújthat alacsonyabb költséggel. Tegye fel magának a kérdést: millió terhelési ciklusnak lesz-e kitéve ez az alkatrész, vagy elsősorban tartós terhelésnek? Jelentősen befolyásolja-e a szemcseáramlási irány a meghibásodás kockázatát?

- Értékelje a geometriai bonyolultságot: Vázolja fel az alkatrészt, és vizsgálja meg különböző tengelyek menti keresztmetszeteit. Leírható-e az egész geometria egyetlen, egyenes vonal mentén elnyújtott 2D-profil segítségével? Ha igen, akkor valószínűleg az extrúzió hatékonyan kezelheti. Szükségesek-e változó keresztmetszetek, elágazások, bordák vagy zárt üregek? Ezek a jellemzők a kovácsolás irányába mutatnak. Szerint iparági irányelvek , ha a modelljének több vázlatra is szüksége van az alakjának leírásához, fontolja meg az űrtartalmat. Az extrudálásos gyártási eljárás akkor nyújt előnyt, ha a geometria végig állandó a rész hossza mentén.

- Értékelje a termelési mennyiség igényeit: Az éves mennyiségi igények jelentősen befolyásolják az eljárás gazdaságosságát. 500 egységnél kisebb sorozatok esetén a szerszámköltségek gyakran dominálnak – az alacsonyabb sablanköltségű extrudálás vagy akár a rúdról történő megmunkálás előnyösebb. 500 és 5 000 egység között mindkét eljárás versenyképes lehet a geometriától függően. 10 000 egységet meghaladó mennyiségek esetén az alkatrészenkénti alacsonyabb költség miatt általában a kovácsolás nyer háromdimenziós alkatrészeknél, annak ellenére, hogy a szerszámköltsége magasabb.

- Vegye figyelembe az anyagi korlátozásokat: Nem minden anyag alkalmas egyformán jól mindkét eljárásra. A acélelemek majdnem mindig a kovácsolást részesítik előnyben, mivel az extrudáláshoz szükséges extrém nyomás nagyon nehézkes acéldugattyúkkal. Az alumínium rugalmasan alkalmazható bármelyik eljárásban. A titán feldolgozási nehézségei miatt erősen a kovácsolás az ajánlott. Ha az anyagmeghatározás az alkalmazás követelményei által rögzített, ez a korlátozás döntheti el a gyártási eljárás választását.

- Számítsa ki a teljes birtoklási költséget: Ne csak az egységárban megadott árra figyeljen. Vegye figyelembe a szerszámamortizációt, a másodlagos megmunkálási igényeket, a selejtarányt, az ellenőrzési költségeket és a potenciális garanciális költségeket is. Egy olcsóbb kovácsolt alkatrész, amelyhez kiterjedt utómegmunkálás szükséges, drágább lehet, mint egy közel nettó formájú alternatíva. Hasonlóképpen, egy olyan extrudált profil, amely hegesztést és szerelést igényel, meghaladhatja egy darab kovácsolt alkatrész költségét.

Gyakori hibák és azok következményei

Annak megértése, hogy mi mehet rosszul, segít elkerülni ugyanezeket a buktatókat. Az alábbiakban a leggyakoribb hibákat soroljuk fel, amelyeket a vállalatok elkövetnek ezen eljárások közötti választáskor:

Extrudálás választása fáradási szempontból kritikus alkatrészekhez: Ha a mérnökök alulbecsülik a ciklikus terhelés súlyosságát, az extrudált alkatrészek előre jelzett időn belül meghibásodhatnak. Az extrudált profilok párhuzamos szemcseszerkezete erősséget biztosít a profil hosszirányában, de kevesebb repedésállóságot nyújt az extrudálás irányára merőlegesen. A felfüggesztési alkatrészek, hajlító igénybevétel alatt álló forgó tengelyek és feszültségkoncentrációkkal rendelkező nyomástartó edények gyakran a kovácsolás többirányú szemcseszerkezetére szorulnak.

A kovácsolás túlméretezése, ha elegendő lenne a profilgyártás: Minden alkatrész kovácsolása a tényleges igények figyelmen kívül hagyásával pénzkidobás, és meghosszabbítja a gyártási időt. Az egyszerű szerkezeti elemek, vezetősinerek és keretprofilok ritkán igénylik a kovácsolás prémium tulajdonságait. Ezt a hibát gyakran a konzervatív mérnöki kultúra okozza, amely költség-haszon elemzés nélkül mindig az „erősebb megoldást” részesíti előnyben.

A másodlagos műveletek költségeinek figyelmen kívül hagyása: Egy kovácsolt és öntött alkatrész összehasonlítása, amely csak a nyers alkatrész költségeit veszi figyelembe, lényeges kiadásokat hagy figyelmen kívül. A melegen kovácsolt alkatrészek általában több utómegmunkálást igényelnek, mint az extrudált profilok. Ha méretpontossági követelményei miatt jelentős CNC-megmunkálás szükséges, az összesített költségkép jelentősen megváltozik. Mindig kérjen teljes árajánlatot, amely tartalmazza az összes műveletet a végleges rajzspecifikációkig.

Ismert beszállítók alapján történő választás: A vállalatok gyakran a meglévő beszállítói kapcsolataik alapján döntenek a gyártási eljárásról, nem pedig a technikai optimalizációt követve. Jelenlegi kovácsoló beszállítója minden igényt kovácsolásként ajánlik fel, még akkor is, ha az extrudálás lenne a célszerűbb megoldás. Hibrid öntött-kovácsolt megközelítések vagy alternatív eljárások jobb eredményt hozhatnak, de ezt sosem fogja megtudni, ha nem lép túl a jelenlegi beszállítói körön.

Amikor egyik eljárás sem optimális

Itt van valami, amit sok forrás nem fog megemlíteni: néha sem a kovácsolás, sem az extrudálás nem a legjobb választás. Ezeknek a helyzeteknek a felismerése megkíméli Önt attól, hogy négyszögletes csapot próbáljon beilleszteni egy kerek lyukba.

Fontolja meg az öntést, ha:

- A geometria belső járatokat, alulmaradásokat vagy olyan rendkívül összetett formákat tartalmaz, amelyeket sem a kovács sablonok, sem az extrúziós sablonok nem tudnak előállítani

- A gyártási mennyiség nagyon alacsony (100 egységnél kevesebb), és a kovácsoláshoz szükséges szerszámok beszerzése nem indokolt

- A felületi pórusosság és az alacsonyabb mechanikai tulajdonságok elfogadhatóak az alkalmazásában

- Több alkatrészt egyetlen öntvényben kíván integrálni, hogy csökkentse az összeszerelési műveleteket

Fontolja meg a rúdanyagból történő megmunkálást, ha:

- A mennyiség rendkívül alacsony (prototípusból akár 50 egységig), és bármilyen szerszámberuházás gyakorlatilag nem lehetséges

- Tervezési változtatások várhatók, így a fix szerszámok bevezetése még korai

- Az alkatrész geometriája hatékonyan megmunkálható szabványos rúdból, lemezből vagy extrudált anyagból

- A szállítási határidő kritikus, és nem várhatja meg a sablonok gyártását

Fontolja meg az additív gyártást, ha:

- A geometriák hagyományos alakítási eljárással nem kivitelezhetők

- Belső rácsstruktúrák vagy topológiai optimalizálású alakzatok szükségesek

- A mennyiségek nagyon alacsonyak, és az anyagköltségek elfogadhatók

- A gyors iteráció és a tervezés érvényesítése fontosabb, mint az egységköltség-gazdaságosság

Az optimális gyártási eljárás az, amely a szükséges teljesítményt a legkisebb összes tulajdonlási költséggel biztosítja – nem feltétlenül az, amelyiknek a legalacsonyabb az egységára vagy a legnagyobbak a mechanikai tulajdonságai.

Ha rendszerszerűen végighalad ezeken a döntési szempontokon, akkor megtalálja a saját igényeihez leginkább illő eljárást, nem pedig automatikusan a feltételezésekre vagy a beszállítói preferenciákra hagyatkozik. Miután felállította a folyamatválasztási keretet, az utolsó lépés egy olyan gyártó kiválasztása, aki képes a kiválasztott módszert folyamatos minőséggel és megbízhatósággal végrehajtani.

A megfelelő gyártópartner kiválasztása

Meghatározta az erősségigényeket, értékelte a geometriai bonyolultságot, és döntött az öntés és az extrudálás között. De itt van a valóság: még a tökéletes folyamatválasztás is kudarcot vallhat, ha gyártási partnere nem képes folyamatosan végrehajtani a munkát. Mire jó egy öntvény, ha nincsenek megfelelő minőségellenőrzési intézkedések a gyártása során? Mennyit ér az öntött alumínium, ha a szállító nem rendelkezik az iparágában előírt tanúsítványokkal?

Minősített gyártó kiválasztása több, mint árajánlatok összehasonlítása. Olyan partnerekre van szüksége, akiknek minőségi rendszere, tanúsítványai és képességei összhangban állnak az alkalmazási követelményeivel. Nézzük meg, hogyan értékelheti a lehetséges beszállítókat, és hogyan egyszerűsítheti a fémalakító ellátási láncát.

Olyan tanúsítási szabványok, amelyek biztosítják az alkatrészek megbízhatóságát

A tanúsítványok hitelesített bizonyítékul szolgálnak arra nézve, hogy a szállító globálisan elismert szabványokat tart fenn a gyártásra, anyagokra és menedzsmentre vonatkozóan. A iparági kutatás szerint az öntvény-szállítók értékeléséről , ezek az igazolások elengedhetetlenek olyan szektorokban, mint a légiközlekedés, az autóipar, a védelem és az energia. Megfelelő tanúsítás nélkül lényegében csak a beszállítói állításokra hagyatkozhat, független ellenőrzés nélkül.

ISO 9001 – A minőség alapja: Ez a tanúsítvány rendszerszerű minőségirányítást igazol, amely magában foglalja a dokumentációt, a képzést, az ügyfélvisszajelzéseket és a folyamatos fejlesztést. Bár az ISO 9001 nem határoz meg konkrét műszaki kovácsolási előírásokat, szervezeti keretet biztosít az összes szakosodott tanúsítvány számára. Minden komoly kovács- vagy sajtolótermelőnek legalább jelenleg érvényes ISO 9001 tanúsítvánnyal kell rendelkeznie.

IATF 16949 – Az autóipari követelmények: Ha kovácsolt vagy extrudált alkatrészeket vásárol autóipari alkalmazásokhoz, az IATF 16949 tanúsítvány elengedhetetlen. Az International Automotive Task Force által létrehozott szabvány az ISO 9001-re épül, és szigorúbb ellenőrzéseket ír elő, amelyek az autóipari ellátási láncokra vannak szabva. A fő hangsúly az előrehaladott termékminőség-tervezésen, a gyártott alkatrészek jóváhagyási folyamatain és a hibák észlelésénél inkább a megelőzésen van. Számos autógyártó nem fogadja el a beszállítókat e nélkül a tanúsítvány nélkül.

AS9100 – Repülési és űripari szektor megfelelősége: Olyan repülési és űripari alkalmazásoknál, ahol egyetlen hiba is katasztrofális meghibásodáshoz vezethet, az AS9100 tanúsítvány elengedhetetlen. Ez az ISO 9001-t bővíti ki olyan repülési és űripari szektorra jellemző előírásokkal, mint a kockázatkezelés, a tervezési ellenőrzés és a teljes terméknyomonkövethetőség. Ez a tanúsítvány azt jelzi, hogy a beszállító folyamatai megfelelnek az iparág legmagasabb követelményeket támasztó minőségbiztosítási rendszereinek.

Nadcap akkreditáció: A főbb repülési- és védelmi ipari gyártók Nadcap akkreditációt követelnek meg azoktól a beszállítóktól, akik különleges eljárásokat, például hőkezelést, rombolásmentes vizsgálatot vagy metallográfiai elemzést végeznek. A Nadcap által akkreditált beszállító világszínvonalú folyamatkonzisztenciát bizonyít. Ez az akkreditáció szigorú, független külső ellenőrzéseket foglal magában, amelyek túlmutatnak a szabványos tanúsítási követelményeken.

További figyelembe veendő tanúsítványok:

- ISO 14001: Környezetmenedzsment tanúsítvány, amely proaktív környezeti hatáskontrollt igazol – egyre fontosabb az ESG-központú ellátási láncok számára

- ISO 45001: Foglalkoztatotti egészség- és biztonsági tanúsítvány, amely rendszerszerű veszélykezelést jelez a kockázatos kovácsolási környezetben

- ISO/IEC 17025: Laboratóriumi akkreditáció, amely megbízható, nyomon követhető vizsgálatokat garantál a húzószilárdság, keménység és mikroszerkezet-elemzés terén

- PED tanúsítvány: Az EU nyomás alatt működő berendezésekhez használt alkatrészek esetében kötelező

Szállítók értékelésekor kérjen másolatot a jelenleg érvényes tanúsítványokról, és ellenőrizze, hogy azok hatálya lefedi-e az Ön alkalmazásához kapcsolódó folyamatokat és anyagokat. Egy alumínium extrúzióra tanúsított szállító nem feltétlen rendelkezik tanúsítvánnyal acélokovácsolási műveletekre.

Fémalakító ellátási lánc optimalizálása

A tanúsítványokon túl a gyakorlati ellátási lánc-tényezők döntik el, hogy sikerül-e a gyártási partnerség. A ciklusidők, a földrajzi elhelyezkedés és a kovácsolóforma-képességek mind hatással vannak arra, hogy képes-e betartani a gyártási ütemtervet és reagálni a piaci igényekre.

Prototípuskészítéstől a sorozatgyártásig terjedő ciklusidők: A prototípusból gyártásba történő átállás számos ellátási láncban kritikus sebezhetőséget jelent. A gyártással kapcsolatos kutatások szerint az űrtartalom-növelés több hónapig, sőt akár egy évnél is tovább tarthat, attól függően, hogy milyen összetett a termék és milyen erőforrások állnak rendelkezésre. Azok a beszállítók, amelyek saját házon belüli sablontervezési és gyártási képességgel rendelkeznek, általában gyorsabb átfutási időt biztosítanak, mint azok, akik kiszervezik a szerszámgyártást.

Például: Shaoyi (Ningbo) Metal Technology bemutatja, hogyan gyorsítják fel az integrált képességek az időkereteket. Az IATF 16949 tanúsítvánnyal és saját házon belüli mérnöki hátterükkel akár már 10 napos gyors prototípusgyártást is kínálnak, miközben fenntartják a nagyüzemi sorozatgyártás kapacitását olyan autóipari alkatrészek esetében, mint a futóműkarok és meghajtó tengelyek. Ez a sebesség és skálázhatóság kombinációja egy gyakori problémát old meg, ahol a beszállítók vagy a prototípusgyártásban, vagy a sorozatgyártásban jeleskednek, de nehézségeik vannak mindkettő hatékony összekapcsolásában.

Földrajzi szempontok globális ellátási láncok esetén: A helyszín nagyobb jelentőséggel bír, mint sok beszerzési csapat gondolná. A főbb hajózási kikötőkhöz való közelség csökkenti a szállítási időt és a fuvarozási költségeket a nemzetközi vásárlók számára. Azok a beszállítók, akik létesített logisztikai központok közelében helyezkednek el, versenyképesebb szállítási ütemtervet és jobb reakcióidőt tudnak biztosítani sürgős rendelések esetén.

Például a Ningbo Kikötőhöz való stratégiai közelség lehetővé teszi a világ egyik legforgalmasabb konténerkikötőjéhez való hozzáférést, amely kiterjedt hajózási útvonalakkal rendelkezik Észak-Amerika, Európa és egész Ázsia felé. Ez a földrajzi előny konkrét előnyökhöz vezet: rövidebb átfutási időkhöz, alacsonyabb szállítási költségekhez és rugalmasabb ütemezési lehetőségekhez globális OEM-ek számára.

Kovácsoló formák képességei és karbantartása: Az állvány minősége közvetlenül befolyásolja az alkatrészek minőségét és a termelési konzisztenciát. Értékelje, hogy a lehetséges beszállítók rendelkeznek-e saját kovácsoló forma tervezési, megmunkálási és hőkezelési képességekkel. Azok a beszállítók, amelyek külső szerszámozási forrásoktól függenek, hosszabb átfutási idővel néznek szembe az állványok javításánál és módosításánál. Szerint egyedi kovácsolási kutatás , a saját tervezőcsoporttal rendelkező gyártók értékes segítséget nyújthatnak a gyártási folyamat és a teljesítmény optimalizálásában.

Minőségbiztosítás a tanúsításon túl: A tanúsítások minimális szabványokat határoznak meg, de a legjobb beszállítók ezeket felülmúlják. Figyeljen oda a komplex tesztelési és ellenőrzési szolgáltatásokra, ideértve:

- Roncsolásmentes vizsgálatok (ultrahangos, mágneses részecskés, festékbeható anyagos)

- Mechanikai tulajdonságok ellenőrzése (szakítóvizsgálat, keménység, ütővizsgálat)

- Méretek ellenőrzése CMM-képességekkel

- Fémkémiai analízis és szemcsestruktúra értékelés

- Statisztikai folyamatszabályozás a folyamatos termelés figyelemmel kíséréséhez

Beszállítói kapacitás és szakértelem értékelése: Egy kovácsoló gyártó tapasztalata jelentős szerepet játszik a végső termék minőségében. Fontolja meg, hogy milyen eredményekkel rendelkeznek Önnél hasonló anyagokkal, az Ön igényeinek megfelelő termelési mennyiségek tekintetében, valamint a mérnöki támogatás elérhetőségében. Azok a gyártók, akik tervezési optimalizálási szolgáltatásokat is kínálnak, jobb eredmények elérésében tudják segíteni Önt, mint akik csupán meglévő rajzok alapján dolgoznak.

A megfelelő folyamat kiválasztása és a megfelelő gyártási partnerek összeegyeztetése a kirakós utolsó darabkája. A legjobb mérnöki döntések sem vezetnek eredményre olyan beszállítók nélkül, akik folyamatosan képesek végrehajtani, hatékonyan skálázni és globálisan szállítani.

Akár sárgaréz extrúziókat vizsgál építészeti alkalmazásokhoz, akár extrudált műanyag profilokat határoz meg ipari berendezésekhez, ugyanazok az alapelvek vonatkoznak a beszállítók értékelésére. Ellenőrizze, hogy a tanúsítványok megfelelnek-e az Ön iparága követelményeinek. Értékelje a gyártási időkereteket a prototípustól a tömeggyártásig. Elemezze a földrajzi elhelyezkedést az ellátási lánc igényeihez. És mindig győződjön meg arról, hogy a minőségbiztosítási rendszerek a papírmunkán túl a tényleges gyártósori gyakorlatokra is kiterjednek.

Ha ötvözi ebben az útmutatóban bemutatott folyamatválasztási keretet a szigorú beszállítói minősítéssel, olyan alakított fémalkatrészeket tud beszerezni, amelyek teljesítményt, megbízhatóságot és értéket nyújtanak, amit alkalmazásai megkövetelnek.

Gyakran ismételt kérdések kovácsolásról és extrúzióról

1. Mi a különbség a kovácsolás és az extrúzió között?

A kovácsolás során kalapácsok vagy sajtok nyomóerejét használják fel a fémrudak háromdimenziós átformálására, így irányított személyszerkezetet hozva létre, amely kiváló szilárdságot biztosít. Az extrudálás hevített fémeket présel át egy formázott sablon, hogy folyamatos, állandó keresztmetszetű profilokat állítsanak elő. A kovácsolás végtermékként alakított, többirányú szilárdságú termékeket hoz létre, míg az extrudálás olyan félig kész profilokat gyárt, amelyek ideálisak csövekhez, rúdokhoz és szerkezeti elemekhez, ahol a terhelés követi a profil hosszát.

2. A székhely. Melyek a négy típusú kovácsolás?

A négy fő kovácsolási típus az alábbiak: nyitott kovácsolás (sima kovácsolóeszközökkel, amelyek nem fogják körül teljesen a munkadarabot), zárt kovácsolás (formázott kovácsolóeszközökkel, amelyek teljesen körülveszik a fém anyagot), lenyomat-kovácsolás (a zárt kovácsolás egyik részfajtája, amely pontosan megmunkált lenyomatokat használ összetett geometriák kialakításához) és hidegkohászat (szobahőmérsékleten végzett eljárás, amely szigorúbb tűrésekkel és jobb felületminőséggel rendelkezik). Mindegyik típus más-más alkalmazásra alkalmas a darab bonyolultságától, a mennyiségi igényektől és a mechanikai tulajdonságok szükségességétől függően.

3. Milyen hátrányai vannak az űrtartalmú acélnak?

A kovácsolt acélalkatrészeknek több korlátozásuk is van: magasabb szerszámköltségek (10 000–100 000 USD felett sablonokért), korlátozott mikroszerkezet-irányítás más eljárásokhoz képest, nagyobb igény másodlagos megmunkálásra, ami költséget és előállítási időt növel, nem lehet porózus csapágyakat vagy többféle fémből álló alkatrészeket gyártani, valamint nehézségek merülnek fel kis vagy finom részletekkel rendelkező alkatrészek létrehozásában további megmunkálás nélkül. A melegkovácsolás emellett felületi oxidációt okoz, amely tisztítást vagy utómegmunkálást igényel.

4. Miben különbözik az extrudálás a hengerléstől és a kovácsolástól?

Az extrudálás során a fémet egy sablonnyíláson keresztül préselik, hogy egységes keresztmetszetű profilokat hozzanak létre, míg az anyag vastagságának csökkentésére vagy alakítására hengerlésnél forgó hengereket használnak. A kovácsolás több irányból ható nyomóerőt alkalmaz a fém háromdimenziós átalakításához. Az extrudálás kiemelkedően alkalmas üreges szakaszok és összetett kétdimenziós profilok előállítására; a kovácsolás a szemcseirányultság révén kiváló fáradási ellenállást biztosít; a hengerlés pedig lapos termékek vagy egyszerű formák nagy mennyiségben történő hatékony gyártására alkalmas.

5. Mikor érdemes a kovácsolást választani az extrudálással szemben a projektje során?

Kovácsolást válasszon, ha az alkatrész több irányból érkező ciklikus terhelésnek van kitéve, maximális fáradásállóságra van szükség, összetett 3D geometriát igényel változó keresztmetszetekkel, vagy a legnagyobb szilárdság-tömeg arányt követeli meg. Az autóipari felfüggesztési karok, repülőgépipari szerelvények és hajtótengelyek általában kovácsolást igényelnek. Egyenletes profilok, üreges szelvények vagy olyan alkalmazások esetén, ahol a terhelések egyetlen tengely mentén hatnak, az extrudálás gyakran elegendő teljesítményt nyújt alacsonyabb szerszámköltségek mellett.

Kis szeletek, magas szabványok. Gyors prototípuskészítési szolgáltatásunk gyorsabbá és egyszerűbbé teszi az ellenőrzést —

Kis szeletek, magas szabványok. Gyors prototípuskészítési szolgáltatásunk gyorsabbá és egyszerűbbé teszi az ellenőrzést —