Elemente esențiale ale matriței de turnare sub presiune: cum funcționează și din ce este realizată

REZUMAT

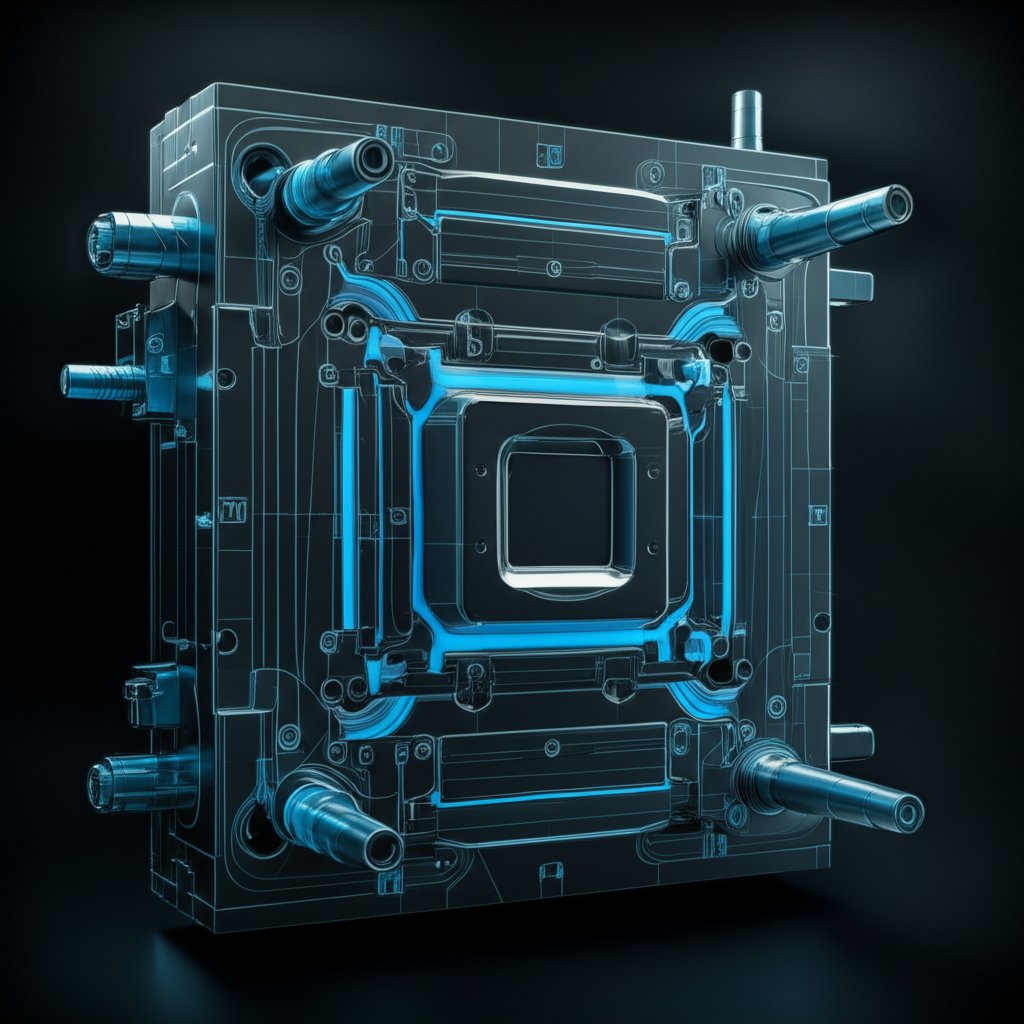

O matriță de turnare sub presiune este un instrument de înaltă precizie, reutilizabil, realizat de obicei din două jumătăți din oțel durificat, care funcționează ca element central al procesului de turnare sub presiune. Metalul topit este forțat în cavitatea matriței sub o presiune foarte mare, permițând producerea în masă a pieselor metalice complexe. Această metodă este cunoscută pentru realizarea componentelor cu o precizie dimensională excepțională și o finisare superficială netedă.

Ce Este o Matriță de Turnare Sub Presiune? Mecanismul Central Explicat

Un tipar de turnare prin injecție, cunoscut și ca matriță sau sculă, este un instrument sofisticat de fabricație utilizat pentru a conferi metalului topit o formă specifică și dorită. În esență, tiparul constă din două jumătăți principale: „semimatrița fixă”, care este staționară, și „semimatrița de ejectare”, care este mobilă. Când aceste două jumătăți sunt strânse împreună sub presiune ridicată, ele formează o cavitate internă care reprezintă negativul exact al piesei ce urmează să fie produsă. Acest proces este conceptual similar cu un tipar de injecție utilizat pentru materiale plastice, dar este proiectat să reziste la temperaturile extreme și la presiunile ridicate ale metalelor topite.

Funcționarea de bază presupune injectarea unui aliaj metalic neferos topit în această cavitate etanșată la viteză și presiune mare. Această presiune este menținută pe durata solidificării metalului, asigurând completarea fiecărui detaliu al cavității matriței. Această tehnică este esențială pentru producerea pieselor cu geometrii complexe și pereți subțiri, care ar fi dificil de realizat prin alte metode de turnare. Odată ce metalul s-a răcit și întărit, jumătatea de evacuare a matriței se retrage, iar un mecanism de ejectare împinge piesa finită afară.

Alegerea metalului este crucială și, deși procesul este cel mai frecvent utilizat pentru aliaje neferoase, nu este limitat exclusiv la acestea. Cele mai utilizate materiale în turnarea sub presiune includ:

- Aliaje de aluminiu

- Aleante de Zinci

- Aleante de Magnesiu

- Aliaje de cupru (cum ar fi alama)

Aceste materiale oferă o gamă de proprietăți, de la rezistență ușoară (aluminiu și magneziu) la o rezistență ridicată la coroziune și capacitate de turnare (zinc). Conform Fictiv , acest proces este ideal pentru producții în volum mare unde consistența și precizia sunt esențiale.

Anatomia unui Matriță de Turnare sub Presiune: Componente Cheie și Funcții

O matriță de turnare sub presiune este mult mai mult decât doar un bloc gol de oțel; este o asamblare complexă de componente proiectate cu precizie care funcționează în mod coordonat. Fiecare parte are un rol critic în ciclul de turnare, de la ghidarea metalului topit până la răcirea piesei și evacuarea acesteia în mod curat. Înțelegerea acestor componente este esențială pentru a aprecia ingineria din spatele procesului. Componentele principale sunt baza matriței, care susține toate celelalte părți, și cavitatea propriu-zisă, care formează forma exterioară a piesei.

Drumul metalului topit este controlat de o rețea de canale. Aceasta începe la este canalul inițial prin care metalul topit intră în tipar din sistemul de injectare. De acolo, , unde metalul intră în matriță dinspre mașina de turnat. canalele de distribuție , care sunt canale prelucrate în jumătățile matriței pentru a distribui metalul. În final, trece prin usă , o deschidere îngustă care direcționează metalul în cavitatea matriței. Proiectarea sistemului de canale și a porții este esențială pentru controlul debitului și presiunii, pentru a preveni defectele.

În interiorul matriței, nucleu formează elementele interne ale piesei, în timp ce cavitate formează suprafețele exterioare ale acesteia. Pentru extragerea piesei finale, sistem de ejector , compus din pene și plăci, împinge turnarea solidificată din matriță. În același timp, un sistem de răcire , format din canale prin care circulă apă sau ulei, reglează temperatura matriței. Acest control este esențial pentru gestionarea timpului de ciclu și pentru prevenirea deteriorării termice a sculei. De asemenea, sunt prevăzute evacuări pentru a permite aerului închis să iasă atunci când metalul este injectat.

| CompoNent | Funcția principală |

|---|---|

| Cavitatea și nucleul matriței | Formează forma exterioară și cea interioară a piesei finale. |

| Este canalul inițial prin care metalul topit intră în tipar din sistemul de injectare. De acolo, | Canalul inițial prin care metalul topit intră în matriță din ajutajul mașinii. |

| Canalele de distribuție | Un sistem de canale care distribuie metalul topit din vasul de alimentare către porți. |

| Usă | Punctul specific de intrare prin care metalul topit curge în cavitatea matriței. |

| Sistem de ejector | Un mecanism compus din pene și plăci care împinge piesa solidificată afară din matriță. |

| Sistem de răcire | O rețea de canale care circulă un fluid pentru a controla temperatura matriței. |

| Ventilații | Canale minuscule care permit scăparea aerului închis și a gazelor din cavitate în timpul injectării. |

Tipuri comune de matrițe și mașini de turnat sub presiune

Matrițele de turnare sub presiune sunt adesea clasificate în funcție de structura lor sau de tipul mașinii pentru care sunt concepute. Din punct de vedere structural, pot fi matrițe cu o singură cavitate, care produc o piesă pe ciclu, sau matrițe cu mai multe cavități, care produc simultan mai multe piese identice pentru o eficiență crescută. Totuși, distincția mai importantă se referă la echipamentul utilizat: turnarea sub presiune cu cameră caldă și cea cu cameră rece.

Turnare în Cochilă cu Cameră Caldă este utilizat pentru aliaje cu puncte de topire scăzute, cum ar fi zincul, staniul și plumbul. În acest proces, mecanismul de injectare este scufundat în baia de metal topit din interiorul cuptorului. Acest lucru permite timpi de ciclu foarte rapizi, deoarece metalul nu trebuie transportat de la un cuptor extern. Procesul este foarte automatizat și eficient pentru producția în volum mare a pieselor mici.

Turnare în Cochilă cu Cameră Rece este necesar pentru aliajele cu puncte de topire ridicate, în special aluminiu și magneziu. În această metodă, o cantitate precisă de metal topit este luată dintr-un cuptor separat și turnată într-o „cameră rece” sau manșon de injectare, înainte de a fi injectată în matriță de către un piston. După cum este detaliat de Wikipedia , această separare este necesară pentru a preveni deteriorarea componentelor de injectare din cauza contactului prelungit cu metalele la temperaturi înalte. Deși timpii de ciclu sunt mai lenti decât în procesul cu cameră caldă, aceasta permite turnarea pieselor structurale puternice și ușoare utilizate în industria auto și aerospațială.

| Aspect | Turnare în Cochilă cu Cameră Caldă | Turnare în Cochilă cu Cameră Rece |

|---|---|---|

| Aliaje potrivite | Punct de topire scăzut (de exemplu, Zinc, Staniu, Plumb) | Punct de topire ridicat (de exemplu, Aluminiu, Alamac, Magneziu) |

| Viteză ciclu | Mai rapid (15+ cicluri pe minut) | Mai lent (mai puține cicluri pe minut) |

| Procesul | Mecanismul de injectare este imersat în metalul topit. | Metalul topit este turnat într-o mânecă de injectare pentru fiecare ciclu. |

| Aplicații tipice | Piese complexe și detaliate, cum ar fi accesorii sanitare, angrenaje și accesorii decorative. | Componente structurale precum blocuri de motor, carcase de transmisie și carcase electronice. |

Procesul de Turnare în Formă și Considerente privind Proiectarea Matriței

Procesul de turnare sub presiune este un ciclu foarte eficient și automatizat care transformă metalul topit într-o piesă finită în câteva secunde. Matrița este elementul central al acestui proces, care poate fi împărțit în mai mulți pași esențiali. Fiecare etapă trebuie controlată cu atenție pentru a asigura faptul că piesa finală respectă standardele stricte de calitate. Materialul din care este realizată matrița este în mod obișnuit un oțel special durificat de înaltă calitate, cum ar fi H13, ales pentru capacitatea sa de a rezista socurilor termice și uzurii pe parcursul a sute de mii de cicluri.

Ciclul de fabricație urmează o succesiune precisă:

- Pregătirea matriței și fixarea: Suprafețele interioare ale matriței sunt pulverizate cu un lubrifiant pentru a facilita răcirea și evacuarea piesei. Cele două jumătăți ale matriței sunt apoi fixate ferm împreună de către mașina de turnare.

- Injecţie: Metalul topit este forțat în cavitatea matriței la presiune ridicată (între 1.500 și peste 25.000 psi). Metalul umple cavitatea rapid, adesea în milisecunde.

- Răcire: Metalul topit se răcește și se solidifică în interiorul matriței răcite cu apă sau ulei. În această fază, piesa își ia forma finală.

- Ejecție: Odată solidificată, jumătatea mobilă a matriței se deschide, iar penele de evacuare împing piesa turnată din cavitate.

- Tăiere: Ultimul pas presupune îndepărtarea materialului în exces, cunoscut sub numele de rebaburi, precum și a canalului de turnare și a canalelor de alimentare, de pe piesa finită. Această operațiune se realizează adesea într-o fază secundară, folosind o matriță de tăiere.

Reușita producției pieselor depinde în mare măsură de proiectarea inițială a matriței. Inginerii trebuie să ia în considerare mai mulți factori pentru a asigura calitatea piesei și pentru a maximiza durata de viață a matriței. O proiectare corectă este esențială pentru prevenirea defectelor frecvente, cum ar fi porozitatea și fisurarea. Principalele aspecte de luat în considerare la proiectare includ:

- Unghi de extracție: Suprafețele paralele cu direcția de deschidere a matriței sunt prevăzute cu un unghi ușor (conicitate) pentru a permite evacuarea piesei fără frecare sau deteriorare.

- Teșituri și raze: Colțurile interne ascuțite sunt rotunjite pentru a îmbunătăți curgerea metalului și pentru a reduce concentrațiile de tensiune în piesa finală.

- Grosime Perete: Peretii trebuie sa fie cat mai uniformi posibil pentru a promova o racire constanta si pentru a preveni deformarea sau semnele de scufundare.

- Linia de separație: Linia de întâlnire a celor două jumătăţi ale formei trebuie plasată cu atenţie pentru a reduce vizibilitatea pe partea finală şi pentru a simplifica tăierea.

- Ventilare: Trebuie să fie incluse canale mici pentru a permite aerului capturat în cavitate să iasă în timp ce se injectează metalul, prevenind porositatea gazelor.

Întrebări frecvente

1. să se Care este diferenţa dintre turnarea prin matriţă şi alte metode de turnare?

Diferența principală constă în utilizarea unei forme de oțel reutilizabile (matrice) și în aplicarea unei presiuni ridicate. Spre deosebire de turnarea cu nisip, care utilizează o matriță de nisip de unică folosință pentru fiecare piesă, turnarea cu matriță utilizează o matriță permanentă din oțel pentru producția în volum mare. În comparație cu turnarea de investiții sau turnarea permanentă a mucegaiului, turnarea prin die forțează metalul în mucegai sub o presiune semnificativ mai mare, permițând crearea de piese cu pereți mai subțiri, detalii mai fine și o finisaj superioară a suprafeței.

2. În cazul în care Ce materiale se folosesc pentru a face o matriţă?

Moldurile de turnare prin matriță sunt fabricate din oțeluri de unelte de înaltă calitate, rezistente la căldură. Cel mai frecvent folosit material este oțelul H13, care este ales pentru combinația excelentă de duritate, rezistență la oboseală termică și rezistență la oboseală. Pentru formele care necesită o durabilitate și mai mare, se pot utiliza oțeluri de calitate superioară, cum ar fi oțelul Maraging. Materialul trebuie să reziste ciclului termic repetat de umplere cu metal topit și apoi răcire.

3. Înveţi să te gândeşti. Cât durează o matriţă?

Durata de viaţă a unei forme de turnare prin matriţă, numită adesea "durată de viaţă a matriţei", variază semnificativ în funcţie de mai mulţi factori. Acestea includ tipul de metal care este turnat (aluminiul este mai abraziv şi mai fierbinte decât zincul), complexitatea piesei, timpul de ciclu şi calitatea întreţinerii. O matriţă de turnare a zincului, bine întreţinută, poate dura peste un milion de cicluri, în timp ce o matriţă de turnare a aluminiului poate dura între 100.000 şi 150.000 de cicluri înainte de a necesita reparaţii majore sau înlocuiri.

Serii mici, standarde ridicate. Serviciul nostru de prototipare rapidă face validarea mai rapidă și mai ușoară —

Serii mici, standarde ridicate. Serviciul nostru de prototipare rapidă face validarea mai rapidă și mai ușoară —